Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

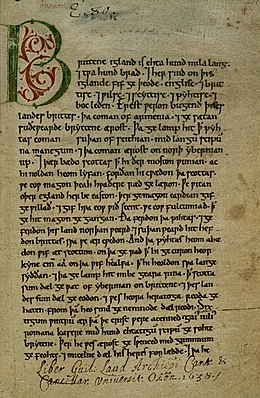

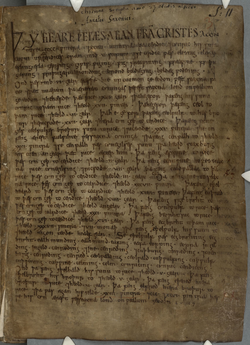

The original manuscript of the Chronicle was created late in the ninth century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of King Alfred the Great (r. 871–899).

Both because much of the information given in the Chronicle is not recorded elsewhere, and because of the relatively clear chronological framework it provides for understanding events, the Chronicle is among the most influential historical sources for England between the collapse of Roman authority and the decades following the Norman Conquest;[3] Nicholas Howe called it and Bede's Ecclesiastical History of the English People "the two great Anglo-Saxon works of history".

[4] The Chronicle's accounts tend to be highly politicised, with the Common Stock intended primarily to legitimise the dynasty and reign of Alfred the Great.

[11][9]: 15 [12][13][14] The patron might have been King Alfred himself (Frank Stenton, for example, argued for a secular household outside the court),[13] and Simon Keynes and Michael Lapidge commented that we should "resist the temptation to regard it as a form of West Saxon dynastic propaganda".

[15] Yet there is no doubt that the Common Stock systematically promotes Alfred's dynasty and rule, and was consistent with his enthusiasm for learning and the use of English as a written language.

[18] Where the Common Stock draws on other known sources its main value to modern historians is as an index of the works and themes that were important to its compilers; where it offers unique material it is of especial historical interest.

These drew on Jerome's De Viris Illustribus, the Liber Pontificalis, the translation of Eusebius's Ecclesiastical History by Rufinus, and Isidore of Seville's Chronicon.

[4][21] From 449, coverage of non-British history largely vanishes and extensive material about the parts of England which by the ninth century were in Wessex, often unique to the Chronicle, appears.

The Chronicle offers an ostensibly coherent account of the Anglo-Saxon settlement of southern Britain by seafarers who, through a series of battles, establish the kingdoms of Kent, Sussex, and Wessex.

This material was once supposed by many historians to be reliable evidence, and formed the backbone of a canonical narrative of early English history; but its unreliability was exposed in the 1980s.

[24] The earliest non-Bedan material here seems to be based primarily on royal genealogies and lists of bishops that were perhaps first being put into writing around 600, as English kings converted to Christianity, and more certainly by the end of the reign of Ine of Wessex (r.

For example, perhaps due to edits in intermediary annals, the beginning of the reign of Cerdic, supposedly the founder of the West-Saxon dynasty, seems to have been pushed back from 538AD in the earliest reconstructable version of the List to 500AD in the Common Stock.

The actual name of the fortress was probably Wihtwarabyrg ("the stronghold of the inhabitants of Wight"), and either the Common Stock editor(s) or an earlier source misinterpreted this as referring to Wihtgar.

[27] In addition to the sources listed above, it is thought that the Common Stock draws on contemporary annals that began to be kept in Wessex during the seventh century, perhaps as annotations of Easter Tables, drawn up to help clergy determine the dates of upcoming Christian feasts, which might be annotated with short notes of memorable events to distinguish one year from another.

[33][34]: 39–60 From the late eighth century onwards, a period coinciding in the text with the beginning of Scandinavian raids on England, the Chronicle gathers momentum.

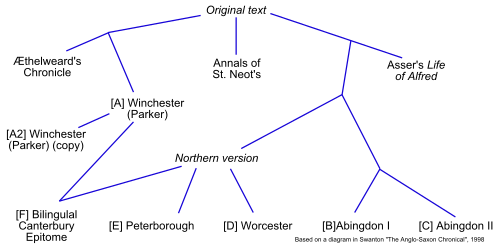

The manuscripts were produced in different places, and at times adaptations made to the Common Stock in the course of copying reflect the agendas of the copyists, providing valuable alternative perspectives.

For example, the Common Stock's annal for 829 describes Egbert's invasion of Northumbria with the comment that the Northumbrians offered him "submission and peace".

The Northumbrian chronicles incorporated into Roger of Wendover's thirteenth-century history give a different picture, however: "When Egbert had obtained all the southern kingdoms, he led a large army into Northumbria, and laid waste that province with severe pillaging, and made King Eanred pay tribute.

Besides [C] emphasizing Ælfgar's innocence, his collaboration with Gruffudd, who is portrayed as a key ally and titled as a Welsh king, is also extensively mentioned.

Conversely, [E] omits Gruffudd's title and focuses on Ælfgar's alleged treachery, framing both figures as aggressors in the Hereford campaign.

Cardiff University historian Rebecca Thomas states this ideological framing aligns with [E]’s broader "pro-Godwine" perspective (referring to the Anglo-Saxon Godwine family dynasty to whom King Harold II belonged) .

Meanwhile, [D] minimizes details of Gruffudd's involvement in the campaign, offering a more subdued account that excludes his royal title and reduces his role to a supporting figure.

"[38] In this case other sources exist to clarify the picture: a major Norwegian attempt was made on England, but [E] says nothing at all, and [D] scarcely mentions it.

Hence the error and the missing sentence must have been introduced in separate copying steps, implying that none of the surviving manuscripts are closer than two removes from the original version.

A manuscript that is now separate (British Library MS. Cotton Tiberius Aiii, f. 178) was originally the introduction to this chronicle; it contains a genealogy, as does [A], but extends it to the late 10th century.

[5] Nowell's transcript copied the genealogical introduction detached from [B] (the page now British Library MS. Cotton Tiberius Aiii, f. 178), rather than that originally part of this document.

The original annalist's entry for the Norman conquest is limited to "Her forðferde eadward kyng"; a later hand added the coming of William the Conqueror, "7 her com willelm.

[46][63] The three main Anglo-Norman historians, John of Worcester, William of Malmesbury and Henry of Huntingdon, each had a copy of the Chronicle, which they adapted for their own purposes.

Titled Chronicon Saxonicum, it printed the Old English text in parallel columns with Gibson's own Latin version and became the standard edition until the 19th century.

[66] It was superseded in 1861 by Benjamin Thorpe's Rolls Series edition, which printed six versions in columns, labelled A to F, thus giving the manuscripts the letters which are now used to refer to them.