Anglo-Saxon royal genealogies

In their fully elaborated forms as preserved in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles and the Textus Roffensis, they continue the pedigrees back to the biblical patriarchs Noah and Adam.

[1] The earliest source for these genealogies is Bede, who in his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (completed in or before 731[2]) said of the founders of the Kingdom of Kent: The two first commanders are said to have been Hengest and Horsa ...

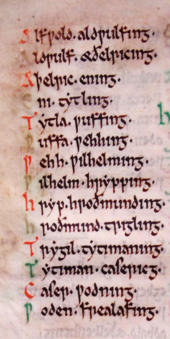

[4] An Anglian collection of royal genealogies also survives, the earliest version (sometimes called Vespasian or simply V) containing a list of bishops that ends in the year 812.

This collection provides pedigrees for the kings of Deira, Bernicia, Mercia, Lindsey, Kent and East Anglia, tracing each of these dynasties from Woden, who is made the son of an otherwise unknown Frealaf.

[5] The same pedigrees, in both text and tabular form, are included in some copies of the Historia Brittonum, an older body of tradition compiled or significantly retouched by Nennius in the early 9th century.

[9] Finally, later interpolations (which were added by 892) to both Asser's Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle preserve Wessex pedigrees extended beyond Cerdic and Woden to Adam.

[10] John of Worcester would copy these pedigrees into his Chronicon ex chronicis, and the 9th-century Anglo-Saxon genealogical tradition also served as a source for the Icelandic Langfeðgatal and was used by Snorri Sturluson for his 13th century Prologue to the Prose Edda.

The euhemerizing treatment of Woden as the common ancestor of the royal houses is presumably a "late innovation" within the genealogical tradition which developed in the wake of the Christianization of the Anglo-Saxons.

Dumville has suggested that these modified pedigrees linking to Wōden were creations intended to express their contemporary politics, a representation in genealogical form of the Anglian hegemony over all the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

These lineages having thus been made to converge, the portion of the pedigree before Woden was then subjected to several successive rounds of extension, and also the interpolation of mythical heroes and other modifications, producing a final genealogy that traced to the Biblical patriarchs and Adam.

The Anglian Collection gives a similar pedigree for Hengest, with Wecta appearing as Wægdæg, and the names Witta and Wihtgils exchanging places, with a similar pedigree being given by Snorri Sturluson in his much later Prologue to the Prose Edda, where Wægdæg, called Vegdagr son of Óðinn, is made a ruler in East Saxony.

[14] From Hengest's son Eoric, called Oisc, comes the name of the dynasty, the Oiscingas, and he is followed as king by Octa, Eormenric, and the well-documented Æthelberht of Kent.

The Prose Edda also gives these names, as Sigarr and Svebdeg alias Svipdagr, but places them a generation farther down the Kent pedigree, as son and grandson of Wihtgils.

It lacks two early generations, a likely scribal error that resulted from a jump between the similar names Siggar and Siggeot, a similar gap appearing in the later pedigree given by chronicler Henry of Huntingdon, whose Historia Anglorum otherwise faithfully follows the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle pedigree, but here jumps directly from 'Sigegeat' to Siggar's father, Wepdeg (Wægdæg).

[17] The pedigree given the kings of Mercia traces their family from Wihtlæg, who is made son (Anglo-Saxon Chronicle), grandson (Anglian collection) or great-grandson (Historia Brittonum) of Woden.

Eliason has suggested that this insertion derives from a byname of Eomer, according to Beowulf the son of a marriage between an Angel and a Geat,[20] but the name may represent an attempt to interpolate the heroic Swedish king Ongenþeow who appears independently in Beowulf and Widsith and in turn is sometimes linked with the earliest historical Danish king, Ongendus, named in Alcuin's 8th-century Vita Willibrordi archiepiscopi Traiectensis.

Eomer, Offa's son or grandson, is then made father of Icel, the legendary eponymous ancestor of the Icling dynasty that founded the Mercian state, except in the surviving version of Historia Brittonum, which skips over not only Icel but Cnebba, Cynwald, and Creoda, jumping straight to Pybba, whose son Penda is the first documented as king, and who along with his 12 brothers gave rise to multiple lines that would succeed to the throne of Mercia through the end of the 8th century.

[22] According to the 9th-century History of the Britons, his father Guillem Guercha (the Wilhelm of the Anglian Collection pedigree) was the first king of the East Angles,[23] but D. P. Kirby is among those historians who have concluded that Wehha was the founder of the Wuffingas line.

[9][26] Finally, later interpolations (which were added by 892) to both Asser's Vita Ælfredi regis Angul Saxonum and the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle preserve Wessex pedigrees extended beyond Cerdic and Woden to Adam.

While the two peoples had no tradition of common origin, their pedigrees share the generations immediately after Woden, Bældæg whom Snorri equated with the God Baldr, and Brand.

Having concluded that the shorter form of the royal genealogy was the original, Sisam compared the names found in different versions of the Wessex and Northumbrian royal pedigrees, revealing a similarity between the Bernician pedigree found in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and those given for Cerdic: rather than diverging several generations earlier they are seen to correspond until the generation immediately before Cerdic, with the exception of one substitution.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle indicates that Ida's reign began in 547, and records him as the son of Eoppa, grandson of Esa, and great-grandson of Ingui.

[42] Richard North suggests that the presence of this Ing- individual among the ancestors of Ida in the Bernician pedigree relates to the Ingvaeones in Germania, referring to the seaboard tribes among which were the Angles who would later found Bernicia.

He hypothesizes that Ingui, representing the same Germanic god as the Norse Yngvi, originally was held to be founder of the Anglian royal families at a time predating the addition of the eponymous Beornuc and extension of the pedigree to Woden.

[46] Ida's successor is given as Glappa, one of his sons, followed by Adda, Æthelric, Theodric, Frithuwald, Hussa, and finally Æthelfrith (d. c. 616), the first Northumbrian monarch known to Bede.

Finally, Alfreið, the king to whom the document traces, is not definitively known elsewhere, but Stenton suggested identification with an Ealdfrid rex who witnessed a confirmation by Offa of Mercia.

These fall into three classes, the shortest being found in the Latin translation of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle prepared by Æthelweard, himself a descendant of the royal family.

The Chronicle and Anglian collection versions appear to have had additional names interpolated into the older tradition reported by Æthelweard, one of them, Heremod, reflecting the legendary ruler of the Danish Scyldings.

[60] Then rather than placing Noah immediately before Sceaf, a long line of names known from Norse and Greek mythology, although not bearing their traditional familial relationships, is added.