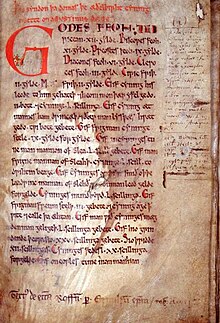

Anglo-Saxon law

By the later Anglo-Saxon period, a system of courts had developed to administer the law, while enforcement was the responsibility of ealdormen and royal officials such as sheriffs, in addition to self-policing (friborh) by local communities.

In the 10th century, a unified Kingdom of England was created with a single Anglo-Saxon government; however, different regions continued to follow their customary legal systems.

[2] Anglo-Saxon law largely derived from unwritten customs termed folk-right (Old English: folcriht, 'right or justice of the people').

[3] The older law of real property, of succession, of contracts, the customary tariffs of fines, were mainly regulated by folk-right.

Writing in the 8th century, the Venerable Bede comments that Æthelberht created his law code "after the examples of the Romans" (Latin: iuxta exempla Romanorum).

Rather, it converted older customs into written legislation, and, reflecting the role of the bishops in drafting it, protected the English church.

In process of time the rights originating in royal grants of privilege overbalanced, as it were, folk-right in many respects, and became themselves the starting-point of a new legal system—the feudal one.

[11] Royal law codes were produced in consultation with the witan, the king's council comprising the lay and ecclesiastical nobility.

For political reasons, these laws were attributed to Edward the Confessor (r. 1042–1066), and "under the guise of the Leges Edwardi Confessoris they achieved an almost mystical authority which inspired Magna Carta in 1215 and were for centuries embedded in the coronation oath.

Wessex formed the core of the unified Kingdom of England, and the royal court at Winchester became the main literary centre.

[18] The Anglo-Saxons developed a sophisticated system of assemblies or moots (the Old English words mot and gemot mean "meeting").

Edgar's law required all sales and purchases (such as land, cattle, and the manumission of slaves) to be witnessed by 12 men chosen by the hundred.

[36] It heard accusations of theft not involving the death penalty and may have executed thieves caught in the act; however, most serious offenses were reserved to the shire court's jurisdiction.

When a crime was committed, the victim or witnesses could raise the "hue and cry", requiring all able-bodied men to pursue the suspect.

[48] The king could also grant the church (either the bishop of a diocese or the abbot of a religious house) the right to administer a hundred.

While common legal procedures existed, they can be difficult to reconstruct due to lack of evidence and variation in local custom.

An example formula in the anonymous text Swerian states, "by the Lord, I accuse N. neither for hatred nor for calumny nor for unjust gain; nor do I know anything more true, except as my informant told me and I myself truly relate that he was the thief of my cattle".

Each side told their version of the facts of the case, which could be supported by witnesses or written evidence (such as the well-known Fonthill Letter).

The Fonthill Letter recounts that a cattle thief named Helmstan was scratched in the face by a bramble while fleeing the scene of the crime.

A defendant was expected to bring oath-helpers (Latin: juratores), neighbors willing to swear to his good character or "oathworthiness".

In the Christian society of Anglo-Saxon England, a false oath was a grave offense against God and could endanger one's immortal soul.

[64] When a defendant failed to establish his innocence by oath in criminal cases (such as murder, arson, forgery, theft and witchcraft), he might still redeem himself through trial by ordeal.

Trial by ordeal was an appeal to God to reveal perjury, and its divine nature meant it was regulated by the church.

[69] The most serious crimes (murder, treachery to one's lord, arson, house-breaking, and open theft) were punishable by death and forfeiture.

A family did not have the right to retaliate if a member was killed while stealing property, committing capital crimes, or resisting capture.

A person was exempt from retaliation if he killed while:[74] Kings and the church promoted financial compensation (Old English: bote) for death or injury as an alternative to blood feuds.

[81][82][44] Slavery may have declined in the late eleventh century as it was considered a pious act for Christians to free their slaves on their deathbed.

Sometimes land was leased to pay back a monetary loan; as part of such an agreement, a lender paid a lump sum of money to the borrower in exchange for the right to collect the loanland's income for a set period (commonly three lives).

[89] Many parts of England (including Kent, East Anglia, and Dorset) practiced forms of partible inheritance in which land was equally divided among heirs.

Failure to receive baptism was punished with a financial penalty, and the oath of a communicant was worth more than a non-communicant in legal proceedings.