Angolan War of Independence

[38][39] The early period of Portuguese incursion was punctuated by a series of wars, treaties and disputes with local African rulers, particularly Nzinga Mbandi, who resisted Portugal with great determination.

From then on, the role of Commander-in-Chief was performed successively by the generals Venâncio Deslandes [pt] (1961–1962, also serving as Governor-General), Holbeche Fino (1962–1963), Andrade e Silva (1963–1965), Soares Pereira (1965–1970), Costa Gomes (1970–1972), Luz Cunha (1972–1974) and Franco Pinheiro (1974), all of them from the Army, except Libório from the Air Force.

So, the previous organization of the former Colonial Military Forces based in company-sized units scattered across Angola, also performing internal security duties, shifted to one along conventional lines, based in three infantry regiments and several battalion-sized units of several arms[clarification needed] concentrated in the major urban centers, aimed at being able to raise an expeditionary field division to be deployed from Angola to reinforce the Portuguese Army in Europe if a conventional war occurred.

Due to the low scale guerrilla nature of the conflict, the caçadores company became the main tactical unit, with the standard organization in three rifle and one support platoons, being replaced by one based in four identical sub-units known as "combat groups".

Later, although skin colour ceased to be an official discriminator, in practice the system changed little—although from the late 1960s onward, blacks were admitted as ensigns (alferes), the lowest rank in the hierarchy of commissioned officers.

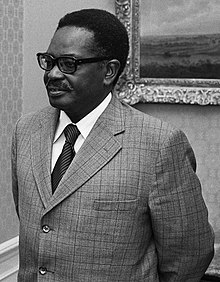

General Costa Gomes, perhaps the most successful counterinsurgency commander, sought good relations with local civilians and employed African units within the framework of an organized counter-insurgency plan.

After 500 years of colonial rule, Portugal had failed to appoint any native black governors, headmasters, police inspectors, or professors, nor a single commander of senior commissioned rank in the overseas Army.

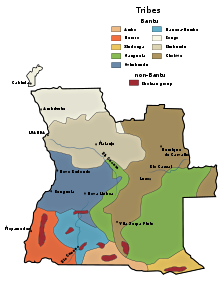

UPA and later the FNLA were mainly supported by the Bakongo ethnic group of the old Kingdom of Kongo, including the Northwestern and Northern Angola, as well as parts of the French and Belgian Congos.

Foreseeing a similar conflict in its African territories, the Portuguese military paid acute attention to this war, sending observers and personnel to be trained in the counter-insurgence warfare tactics employed by the French.

The intention of Galvão was to set sail to Angola, where he would disembark and establish a rebel Portuguese government in opposition to Salazar, but he was forced to head to Brazil, where he liberated the crew and passengers in exchange for political asylum.

The Baixa do Cassanje was a rich agricultural region of the Malanje District, bordering the ex-Belgian Congo, with approximately the size of Mainland Portugal, which was the origin of most of the cotton production of Angola.

Despite its contribution for the development of the region, Cotonang had been accused several times of disrespecting the labour legislation regarding working conditions of its employees, causing it to become under the investigation of the Portuguese authorities, but with no relevant actions against it being yet taken.

Presumably due to this belief, the rebels, armed with machetes and canhangulos (home-made shotguns), attacked the military en masse, in the open field, without concern for their own protection, falling under the fire of the troops.

After the subdue of the uprising, the Portuguese military pressed the Government-General of Angola to take actions to improve the working conditions of the Cotonang employees in order to solve definitely the situation.

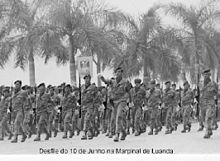

[citation needed] At a time when Luanda was full of foreign journalists that were covering the possible arriving at Angola of the hijacked liner Santa Maria and with the Baixa de Casanje revolt on its peak, on the early morning of 4 February 1961,[citation needed] a number of black militants, mostly armed with machetes, ambushed a Public Security Police (PSP) patrol-car and stormed the Civil Jail of São Paulo, the Military Detection House and the PSP Mobile Company Barracks, with the apparent objective of freeing political prisoners that were being held in those facilities.

The anti-Portuguese line states that the riots were originated by the whites, who desired to revenge the dead police constables, committing random acts of violence against the ethnic black majority living in Luanda's slums (musseques).

It must be said that many of these people were probably disarmed, even the force that was going to make the salvos of the order, to accompany the highest individualities of Luanda and that it was a military vehicle called on the occasion, that came to the place, and ended the generalized disorder.

[58] UPA militants stormed the Angolan districts of Zaire Province, Uíge, Cuanza Norte and Luanda, massacring the civilian population during their advance, killing 1,000 whites and 6,000 blacks (women and children included in both numbers).

Instead, they entrenched themselves in several towns and villages of the region – including Carmona, Negage, Sanza Pombo, Santa Cruz, Quimbele and Mucaba – resisting the assaults almost without the support of the few existent military forces.

Following the aborted coup and now realizing that the conflict in Angola was more serious than what was initially thought, Prime Minister Salazar dismissed Botelho Moniz and assumed himself the Defense portfolio.

On 10 April, the Operation Esmeralda (Emerald) – aimed at cleaning and retaking the control of Pedra Verde, UPA's last base in northern Angola – was initiated by the Special Caçadores Battalion 261, supported by paratroopers, artillery, armored cars and aviation elements.

On 9 June, the United Nations Security Council adopted Resolution 163, declaring Angola a non-self-governing territory and calling on Portugal to desist from repressive measures against the Angolan people.

[65] The major military operations finally terminated on 3 October, when a platoon of the Artillery Company 100 reoccupied Caiongo, in the circle of Alto Cauale, Uíge, the last abandoned administrative post that remained unrecovered.

In addition to the change in leadership, the MPLA adopted and reaffirmed its policies for an independent Angola:[46] Savimbi left the FNLA in 1964 and founded UNITA in response to Roberto's unwillingness to spread the war outside the traditional Kingdom of Kongo.

[37][77] The MFA overthrew the Lisbon government in protest against the authoritarian political regime and the ongoing African colonial wars, specially the particularly demanding conflict in Portuguese Guinea.

Holden Roberto, Agostinho Neto, and Jonas Savimbi met in Bukavu, Zaire in July and agreed to negotiate with the Portuguese as one political entity, but afterwards the fight broke out again.

In July, fighting again broke out and the MPLA managed to force the FNLA out of Luanda; UNITA voluntarily withdrew from the capital to its stronghold in the south from where it also engaged in the struggle for the country.

Many analysts have blamed the transitional government in Portugal for the violence that followed the Alvor Agreement, criticizing the lack of concern about internal Angolan security, and the favoritism towards the MPLA.

[80][86] Secretary of State Henry Kissinger considered any government involving the pro-Soviet, communist MPLA, to be unacceptable and President Gerald Ford oversaw heightened aid to the FNLA.

Like the other newly independent African territories involved in the Portuguese Colonial War, Angola's rank in the human development and GDP per capita world tables fell.