Animal navigation

Birds such as the Arctic tern, insects such as the monarch butterfly and fish such as the salmon regularly migrate thousands of miles to and from their breeding grounds,[1] and many other species navigate effectively over shorter distances.

William Tinsley Keeton showed that homing pigeons could similarly make use of a range of navigational cues, including the Sun, Earth's magnetic field, olfaction and vision.

Insects and birds are able to combine learned landmarks with sensed direction (from the Earth's magnetic field or from the sky) to identify where they are and so to navigate.

In 1873, Charles Darwin wrote a letter to Nature magazine, arguing that animals including man have the ability to navigate by dead reckoning, even if a magnetic 'compass' sense and the ability to navigate by the stars is present:[2] With regard to the question of the means by which animals find their way home from a long distance, a striking account, in relation to man, will be found in the English translation of the Expedition to North Siberia, by Von Wrangell.

[a] He there describes the wonderful manner in which the natives kept a true course towards a particular spot, whilst passing for a long distance through hummocky ice, with incessant changes of direction, and with no guide in the heavens or on the frozen sea.

This is effected chiefly, no doubt, by eyesight, but partly, perhaps, by the sense of muscular movement, in the same manner as a man with his eyes blinded can proceed (and some men much better than others) for a short distance in a nearly straight line, or turn at right angles, or back again.

Now, it is conceivably quite possible, though such delicacy of mechanism is not to be hoped for, that a machine should be constructed … for registering the magnitude and direction of all these shocks, with the time at which each occurred … from these data the position of the carriage … might be calculated at any moment.Karl von Frisch (1886–1982) studied the European honey bee, demonstrating that bees can recognize a desired compass direction in three different ways: by the Sun, by the polarization pattern of the blue sky, and by the Earth's magnetic field.

[4] William Tinsley Keeton (1933–1980) studied homing pigeons, showing that they were able to navigate using the Earth's magnetic field, the Sun, as well as both olfactory and visual cues.

They do so, of course, without any visible compass, sextant, chronometer or chart...Many mechanisms of spatial cognition have been proposed for animal navigation: there is evidence for a number of them.

[10][11] Investigators have often been forced to discard the simplest hypotheses - for example, some animals can navigate on a dark and cloudy night, when neither landmarks nor celestial cues like Sun, Moon, or stars are visible.

Animals including mammals, birds and insects such as bees and wasps (Ammophila and Sphex),[12] are capable of learning landmarks in their environment, and of using these in navigation.

Honey bees can use polarized light on overcast days to estimate the position of the Sun in the sky, relative to the compass direction they intend to travel.

Karl von Frisch's work established that bees can accurately identify the direction and range from the hive to a food source (typically a patch of nectar-bearing flowers).

[4] Some animals, including mammals such as blind mole rats (Spalax)[25] and birds such as pigeons, are sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field.

Many marine animals such as seals are capable of hydrodynamic reception, enabling them to track and catch prey such as fish by sensing the disturbances their passage leaves behind in the water.

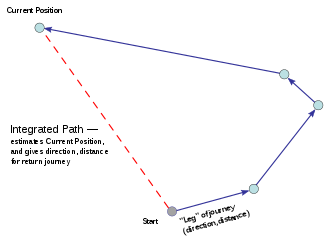

[39] Since Darwin's On the Origins of Certain Instincts[2] (quoted above) in 1873, path integration has been shown to be important to navigation in animals including ants, rodents and birds.

[40][41] When vision (and hence the use of remembered landmarks) is not available, such as when animals are navigating on a cloudy night, in the open ocean, or in relatively featureless areas such as sandy deserts, path integration must rely on idiothetic cues from within the body.

[42][43] Studies by Wehner in the Sahara desert ant (Cataglyphis bicolor) demonstrate effective path integration to determine directional heading (by polarized light or sun position) and to compute distance (by monitoring leg movement or optical flow).