Animal consciousness

[2][3] In humans, consciousness has been defined as: sentience, awareness, subjectivity, qualia, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind.

[11] In 1927, the American functional psychologist Harvey Carr argued that any valid measure or understanding of awareness in animals depends on "an accurate and complete knowledge of its essential conditions in man".

[12] A more recent review concluded in 1985 that "the best approach is to use experiment (especially psychophysics) and observation to trace the dawning and ontogeny of self-consciousness, perception, communication, intention, beliefs, and reflection in normal human fetuses, infants, and children".

For example, it is not the feeling of fear that produces an increase in heart beat, both are symptomatic of a common physiological origin, possibly in response to a legitimate external threat.

In the early 1900s scientific behaviorists such as Ivan Pavlov, John B. Watson, and B. F. Skinner began the attempt to uncover laws describing the relationship between stimuli and responses, without reference to inner mental phenomena.

[29] In his interactions with scientists and other veterinarians, Rollin asserts that he was regularly asked to prove animals are conscious and provide scientifically acceptable grounds for claiming they feel pain.

[32][33] A refereed journal Animal Sentience[34] launched in 2015 by the Institute of Science and Policy of The Humane Society of the United States is devoted to research on this and related topics.

"[44] Related terms, also often used in vague or ambiguous ways, are: Sentience (the ability to feel, perceive, or to experience subjectivity) is not the same as self-awareness (being aware of oneself as an individual).

[46][47] It remains debatable whether recognition of one's mirror image can be properly construed to imply full self-awareness,[48] particularly given that robots are being constructed which appear to pass the test.

Damasio has demonstrated that emotions and their biological foundation play a critical role in high level cognition,[54][55] and Edelman has created a framework for analyzing consciousness through a scientific outlook.

[61]Consciousness in mammals (including humans) is an aspect of the mind generally thought to comprise qualities such as subjectivity, sentience, and the ability to perceive the relationship between oneself and one's environment.

[63] In a new study conducted in rhesus monkeys, Ben-Haim and his team used a process dissociation approach that predicted opposite behavioral outcomes for the two modes of perception.

Self-awareness by this criterion has been reported for: Until recently, it was thought that self-recognition was absent in animals without a neocortex, and was restricted to mammals with large brains and well-developed social cognition.

The intrepid Midgley, on the other hand, seems willing to speculate about the subjective experience of tapeworms ...Nagel ... appears to draw the line at flounders and wasps, though more recently he speaks of the inner life of cockroaches.

In an article written for The New York Times, Carol Kaesuk Yoon argues that: When a plant is wounded, its body immediately kicks into protection mode.

Inside the plant, repair systems are engaged and defenses are mounted, the molecular details of which scientists are still working out, but which involve signaling molecules coursing through the body to rally the cellular troops, even the enlisting of the genome itself, which begins churning out defense-related proteins ...

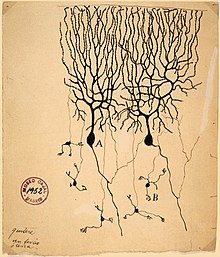

The scope of neuroscience has broadened recently to include molecular, cellular, developmental, structural, functional, evolutionary, computational, and medical aspects of the nervous system.

Take, as an example, the incredible fine motor skills exerted in playing a Beethoven piano sonata or the sensorimotor coordination required to ride a motorcycle along a curvy mountain road.

[106] A combination of such fine-grained neuronal analysis in animals with ever more sensitive psychophysical and brain imaging techniques in humans, complemented by the development of a robust theoretical predictive framework, will hopefully lead to a rational understanding of consciousness.

[citation needed] There is evidence that rhesus monkeys and apes can make accurate judgments about the strengths of their memories of fact and monitor their own uncertainty,[119] while attempts to demonstrate metacognition in birds have been inconclusive.

In a study published in March 2005, Iacoboni and his colleagues reported that mirror neurons could discern if another person who was picking up a cup of tea planned to drink from it or clear it from the table.

[133][134] Consciousness is likely an evolved adaptation since it meets George Williams' criteria of species universality, complexity,[135] and functionality, and it is a trait that apparently increases fitness.

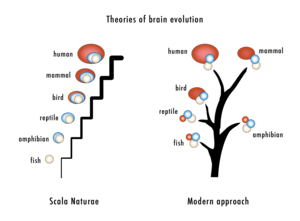

[139] In contrast, others have argued that the recursive circuitry underwriting consciousness is much more primitive, having evolved initially in pre-mammalian species because it improves the capacity for interaction with both social and natural environments by providing an energy-saving "neutral" gear in an otherwise energy-expensive motor output machine.

In considering how the neural mechanisms underlying primary consciousness arose and were maintained during evolution, it is proposed that at some time around the divergence of reptiles into mammals and then into birds, the embryological development of large numbers of new reciprocal connections allowed rich re-entrant activity to take place between the more posterior brain systems carrying out perceptual categorization and the more frontally located systems responsible for value-category memory.

[147][148] Ursula Voss of the Universität Bonn believes that the theory of protoconsciousness[149] may serve as adequate explanation for self-recognition found in birds, as they would develop secondary consciousness during REM sleep.

[155] A common image is the scala naturae, the ladder of nature on which animals of different species occupy successively higher rungs, with humans typically at the top.

[160][161] A 2015 study claims that the "sniff test of self-recognition" (STSR) provides significant evidence of self-awareness in dogs, and could play a crucial role in showing that this capacity is not a specific feature of only great apes, humans and a few other animals, but it depends on the way in which researchers try to verify it.

[163] Research with captive grey parrots, especially Irene Pepperberg's work with an individual named Alex, has demonstrated they possess the ability to associate simple human words with meanings, and to intelligently apply the abstract concepts of shape, colour, number, zero-sense, etc.

[166] In 2011, research led by Dalila Bovet of Paris West University Nanterre La Défense, demonstrated grey parrots were able to coordinate and collaborate with each other to an extent.

[174] Unlike vertebrates, the complex motor skills of octopuses are not organized in their brain using an internal somatotopic map of their body, instead using a non-somatotopic system unique to large-brained invertebrates.