Animal testing on non-human primates

In December 2006, an inquiry chaired by Sir David Weatherall, emeritus professor of medicine at Oxford University, concluded that there is a "strong scientific and moral case" for using primates in some research.

[5] The British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection argues that the Weatherall report failed to address "the welfare needs and moral case for subjecting these sensitive, intelligent creatures to a lifetime of suffering in UK labs".

Blakemore, while stressing he saw no "immediate need" to lift the ban, argued "that under certain circumstances, such as the emergence of a lethal pandemic virus that only affected the great apes, including man, then experiments on chimps, orang-utans and even gorillas may become necessary."

The use of great apes is generally not permitted, unless it is believed that the actions are essential to preserve the species or in relation to an unexpected outbreak of a life-threatening or debilitating clinical condition in human beings.

[25] Eighty-two percent of primate procedures in the UK in 2006 were in applied studies, which the Home Office defines as research conducted for the purpose of developing or testing commercial products.

This includes neuroscientific study of the visual system, cognition, and diseases such as Parkinson's,[47] involving techniques such as inserting electrodes to record from or stimulate the brain, and temporary or permanent inactivation of areas of tissue.

[48] This is contradicted by Dr. Gill Langley of the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection, who gives as an example of re-use the licence granted to Cambridge University to conduct brain experiments on marmosets.

Reinhardt writes that primatologists have long recognized that restraint methods may introduce an "uncontrolled methodological variable", by producing resistance and fear in the animal.

"Numerous reports have been published demonstrating that non-human primates can readily be trained to cooperate rather than resist during common handling procedures such as capture, venipuncture, injection and veterinary examination.

The NIH called for the study after protests by the Humane Society of the United States, primatologist Jane Goodall and others, when it announced plans to move 186 semi-retired chimpanzees back into active research.

Later that day Francis Collins, a head of the NIH, said the agency would stop issuing new awards for research involving chimpanzees until the recommendations developed by the IOM are implemented.

The panel concluded that the animals provide little benefit in biomedical discoveries except in a few disease cases which can be supported by a small population of 50 primates for future research.

[82][83] In the 1940s, Jonas Salk used rhesus monkey cross-contamination studies to isolate the three forms of the polio virus that crippled hundreds of thousands of people yearly across the world at the time.

[86] In the 1950s, Roger Sperry developed split-brain preparations in non-human primates that emphasized the importance of information transfer that occurred in these neocortical connections.

Those experiments were followed by tests on human beings with epilepsy who had undergone split-brain surgery, which established that the neocortical connections between hemispheres are the principal route for cognition to transfer from one side of the brain to another.

In the 1960s, David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel demonstrated the macrocolumnar organization of visual areas in cats and monkeys, and provided physiological evidence for the critical period for the development of disparity sensitivity in vision (i.e., the main cue for depth perception).

Over the next seven years, the brain areas that were over- and under-active in Parkinson's were mapped out in normal and MPTP-treated macaque monkeys using metabolic labelling and microelectrode studies.

"The comparison and correlation of results obtained in monkey and human studies is leading to a growing validation and recognition of the relevance of the animal model.

Although each animal model has its limitations, carefully designed drug studies in nonhuman primates can continue to advance our scientific knowledge and guide future clinical trials.

"[88][89][90] The reason for studying primates is due to the similar complexity of the cerebral processes in the human brain which controls emotional responses and can be beneficial for testing new pharmacological treatments.

Scientist Barros and his colleagues created this model to allow the monkeys to roam a less confined environment and slightly eliminate outside factors that may induce stress.

According to UCR officials, the ALF claims of animal mistreatment were "absolutely false," and the raid would result in long-term damage to some of the research projects, including those aimed at developing devices and treatment for blindness.

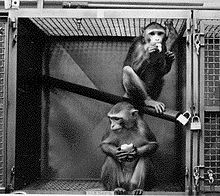

In Germany in 2004, journalist Friedrich Mülln took undercover footage of staff at Europe's largest primate-testing center in Münster, operated by Fortrea.

The monkeys were shown isolated in small wire cages with little or no natural light, no environmental enrichment, and subjected to high noise levels from staff shouting and playing the radio.

A veterinary toxicologist employed as a study director at a Fortrea facility in Vienna, Virginia, from 2002 to 2004, told city officials in Chandler, Arizona, that the company was dissecting monkeys while the animals were still alive and able to feel pain.

In the UK, after an undercover investigation in 1998, the British Union for the Abolition of Vivisection (BUAV), a lobby group, reported that researchers in Cambridge University's primate-testing labs were sawing the tops off marmosets' heads, inducing strokes, then leaving them overnight without veterinarian care, because staff worked only nine to five.

"[104] The baboons were kept alive after the surgery for observation for three to ten days in a state of "profound disability" which would have been "terrifying," according to neurologist Robert Hoffman.

The Dean of Research at Columbia's School of Medicine said that Connolly had stopped the experiments because of threats from animal rights activists, but still believed his work was humane and potentially valuable.

His name, phone number, and address were posted on the website of the UCLA Primate Freedom Project, along with a description of his research, which stated that he had "received a grant to kill 30 macaque monkeys for vision experiments.

[citation needed] The house of UCLA researcher Edythe London was intentionally flooded on October 20, 2007, in an attack claimed by the Animal Liberation Front.