Annexation of Savoy

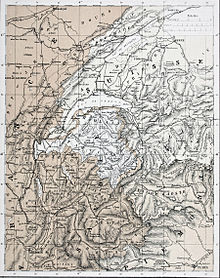

Despite the country's history of occupation and annexation by various powers, including the French (from 1536 to 1559, from 1600 to 1601, 1689, and then from 1703 to 1713) and the Spaniards (from 1742 to 1748), the expression in question pertains to the "union" clause outlined in Article 1 of the Treaty of Turin of March 24, 1860.

The expression is also used about the "union" clause in Article 1 of the Treaty of Turin of March 24, 1860,[Note 1] which pertains to the historical fact that France and Savoy had been jointly ruled during the Carolingian Empire.

He notes that the history of Savoy, on a large scale, is not exempt from these tensions, as evidenced by the ongoing debates surrounding the millennium of the dynasty, the Revolution, the Annexation, and the Resistance.

However, the designation is considerably more prevalent in the northern reaches of the region[Note 2] than in the south, where Chambéry, the erstwhile capital of the duchy, has renamed it "General-de-Gaulle Avenue".

Subsequently, a treaty was signed in Turin on January 26, 1859, to formalize the Franco-Piedmontese alliance by Prince Napoleon Jérôme, who married Princess Clotilde of Savoy four days later.

On July 25, 1859, approximately twenty-five or thirty Savoyard individuals, lacking notable political or economic influence, primarily from Chambéry, led by Dr. Gaspard Dénarié [fr] and lawyer Charles Bertier,[10] editor-in-chief of the conservative newspaper Courrier des Alpes [fr], presented an address to King Victor Emmanuel II of Savoy, requesting his consideration of the desires of the ducal province.

[12] This address was the subject of a petition throughout Savoy, marking the beginning of an opinion movement across the country, notably through the Savoyard, Turin, Geneva, and French press.

In the days that followed, on July 28, 1859, in Annecy, a group of approximately a dozen Savoyard deputies, all of whom identified as conservative Catholics, petitioned the government to address the material fate of the province of Savoy.

[16] In the period between December 1859 and January 1860, the government dispatched clandestine emissaries to ascertain the prevailing sentiment among the Savoyard populace regarding the proposed union with the French Empire.

De Montfalcon, among others, was supported by approximately forty individuals who published a Déclaration on February 15, 1860, denouncing the potential division of Savoy as a violation of its historical and cultural identity.

They asserted that such a move would be detrimental to the region's pride and sense of national identity, and would be perceived as an insult to the deeply held values and aspirations of the Savoyard people.

On March 1, 1860, Napoleon III proclaimed to the Legislative Body his intention to claim the gratuity agreed upon at Plombières, namely, the western slope of the Alps mountains,[23] comprising Nice and Savoy, in exchange for his support for Italian unity.

The duchy's divisional councils convened and resolved to dispatch a delegation of 41 Savoyards (nobles, bourgeois, and ministerial officers) in favor of annexation.

[Note 7] This delegation was to be led by Count Amédée Greyfié de Bellecombe [fr][24] and would receive a solemn reception at the Tuileries from the Emperor on March 21, 1860.

On March 28, 1860, an armed delegation from Switzerland, led by the secretary of the foreign office, Jules-César Ducommun [fr], and composed of French anti-Bonapartist refugees, departed from Geneva to join the town of Bonneville.

The delegation, which had assumed the guise of Northern Savoyards, supporters of annexation to Switzerland, attempted to galvanize the inhabitants by proclaiming, "Let us extend our arms to this Swiss homeland that our ancestors dreamed of and that must bring us well-being and freedom.

[33] On the following day, March 29, 1860, the radical Geneva deputy John Perrier, who was known as Perrier-le-Rouge and had previously worked as a goldsmith, accompanied by an armed Swiss delegation, went to Thonon-les-Bains intending to incite an uprising.

Merged with ours, your interests will henceforth be the constant concern of the sovereign who has elevated the glory and prosperity of France so high.To commemorate the event, a series of traditional celebrations were held in the rural and urban communities of Savoy over several days.

On March 30, 1860, Bishop Billiet penned a missive to the emperor, in which he stated: Sire, the clergy of Savoy has always considered it a duty to set an example of loyalty to its sovereign.

I would, however, venture to state to Your Majesty two things that might cause some concern: the presumed reduction of dioceses and civil marriage opposed to the purity of Catholic morality.

Bishop Alexis Billiet was elevated to the rank of Cardinal to circumvent potential disputes that might arise from the abolition of six feast days, including that of Saint Francis de Sales.

At the behest of the King of Sardinia, Napoleon III consented to establish a religious office at Hautecombe Abbey, operating under the aegis of the Archdiocese of Chambéry.

[Note 12] Those Savoyard soldiers who elected to serve in the French military were assembled in the 103rd line infantry regiment, stationed in Sathonay, near Lyon, and Châlons-sur-Marne.

Nevertheless, some mining areas employed approximately twenty workers each in Saint-Georges-des-Hurtières in Maurienne, Randens, Argentine, and Peisey-Macôt, with the vast majority of production being sold to Piedmont.

[43] Industrial installations in the Faucigny province, powered by traditional hydraulic force, were listed in a survey conducted by deputy Charles-Marie-Joseph Despine [fr] (1792–1856) before his death.

The Mont-Cenis railway tunnel became an essential link for the transportation of goods and passengers between Italy and France, including trains carrying automobiles.

[45] To demonstrate to the Parisian bourgeoisie the newly attached provinces of Savoy, Napoleon III commissioned approximately thirty color lithographs portraying the landscapes and towns of the region.

In commemoration of the 150th anniversary of the annexation, the local authorities of Savoy and Haute-Savoie, in collaboration with learned societies and associations, organized a series of historical conferences, university colloquia, exhibitions, and other events to reach other departments.

In this year of celebration, on June 6, 2010, Deputy Yves Nicolin posed a question regarding "the significant legal, political, and institutional risks posed by the annexation treaty of Savoy: Whether the annexation treaty of Savoy of March 24, 1860, was registered with the United Nations Secretariat and, if not, what measures the government is taking to address the subsequent legal issues.

This could be attributed to the disillusionment of certain individuals or to the pride that these festivities instilled in Savoyards, which provided an opportunity to reaffirm a distinct identity within the broader French context.