Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security between the United States and Japan

The amended treaty included articles delineating mutual defense obligations and requiring the US, before mobilizing its forces, to inform Japan in advance.

[6] The United States agreed to a revision, negotiations began in 1958, and the new treaty was signed by Eisenhower and Kishi at a ceremony in Washington, D.C., on January 19, 1960.

Article 6 explicitly grants the United States the right to base troops in Japan, subject to a detailed "Administrative Agreement" negotiated separately.

Article 8 states that the treaty will be ratified by the US and Japan in accordance with their respective constitutional processes and will go into effect the date they are signed and exchanged in Tokyo.

[12] Faced with popular opposition in the streets and Socialist Party stonewalling in the National Diet, Prime Minister Kishi grew increasingly desperate to pass the treaty in time for Eisenhower's scheduled arrival in Japan on June 19.

[19] However, he was talked out of these extreme measures by his cabinet, and thereafter had no choice but to cancel Eisenhower's visit, for fears that his safety could not be guaranteed, and to announce his own resignation as Prime Minister, in order to quell the widespread popular anger at his actions.

Although Kishi was forced to resign and Eisenhower's visit was cancelled, under Japanese law, the treaty was automatically approved 30 days after passing the Lower House of the Diet.

[20] However, once the treaty entered into force and Kishi resigned from office, the anti-treaty protest movement lost momentum and rapidly died away.

[21] The anti-American aspect of the protests and the humiliating cancellation of Eisenhower's visit brought U.S.-Japan relations to their lowest ebb since the end of World War II.

[22] At their June 1961 summit meeting, the two leaders agreed that henceforth the two nations would consult much more closely as allies, along lines similar to the relationship between the United States and Great Britain.

[24] The difficult process of securing the passage of the revised treaty and the violent protests it caused contributed to a culture of secret pacts (密約, mitsuyaku) between the two nations.

However, prime minister Eisaku Satō (who was Kishi's younger brother) opted to ignore the protests completely and allow the treaty to automatically renew.

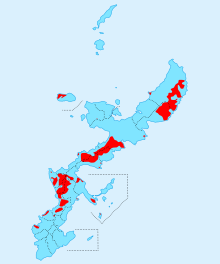

[5] A central issue in the debate over the continued U.S. military presence is the heavy concentration of troops in the small Japanese prefecture of Okinawa.

[26][5] Base-related frictions, disputes, and environmental problems have left many Okinawans feeling that while the security agreement may be beneficial to the United States and Japan as a whole, they bear a disproportionate share of the burden.

Prolonged exposure to high-decibel noise pollution from the American military jets flying over residential areas in Okinawa has been found to cause heart problems, disrupt sleep patterns, and damage cognitive skills in children.

[27][30] The most powerful opposition in Okinawa, however, stemmed from criminal acts committed by US service members and their dependents, with the latest example being the 1995 kidnapping and molestation of a 12-year-old Okinawan girl by two Marines and a Navy corpsman.

[5] In early 2008, U.S. Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice apologized after a series of crimes involving American troops in Japan, including the rape of a girl of 14 by a marine on Okinawa.