Anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States

Racial prejudice against Asian immigrants began building soon after Chinese workers started arriving in the country in the mid-19th century, and set the tone for the resistance Japanese would face in the decades to come.

Although Chinese were heavily recruited in the mining and railroad industries initially, whites in Western states and territories came to view the immigrants as a source of economic competition and a threat to racial purity as their population increased.

A network of anti-Chinese groups (many of which would reemerge in the anti-Japanese movement) worked to pass laws that limited Asian immigrants' access to legal and economic equality with whites.

[3] Anti-Japanese racism and fear of the Yellow Peril had become increasingly xenophobic in California after the Japanese victory over the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War.

On October 11, 1906, the San Francisco, California Board of Education passed a regulation whereby children of Japanese descent would be required to attend racially segregated and separate schools.

In State of California v. Jukichi Harada (1918), Judge Hugh H. Craig[6] sided with the defendant and ruled that American children – who happened to be born to Japanese parents – had the right to own land.

Passage of the Immigration Act contributed to the growth of anti-Americanism and ending of a growing democratic movement in Japan during this time period, opening the door to Japanese militarist government control.

African American sentiments at the time could be quite different than the mainstream, with organizations like the Pacific Movement of the Eastern World (PMEW) which promised equality and land distribution under Japanese rule.

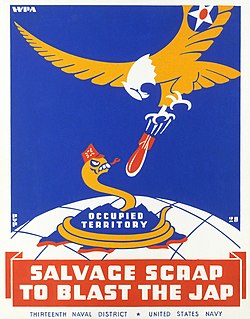

The most profound cause of anti-Japanese sentiment outside of Asia had its beginning in the attack on Pearl Harbor, as it propelled the United States into World War II.

The bombing of Pearl Harbor by Japan on the neutral United States without warning and the deaths of almost 2,500 people during ongoing U.S./Japanese peace negotiations was presented to the American populace as an act of treachery, barbarism, and cowardice.

[14] The Guadalacanal Diary, which was published in 1943, wrote about the accounts of American soldiers, collecting Japanese 'gold teeth' or body parts such as hands or ears, to keep as trophies.

[18] Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist, believed that front line troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners.

The hysteria which enveloped the West Coast during the early months of the war, combined with long standing anti-Asian prejudices, set the stage for what was to come.

Kamikaze suicide bombings, according to John Morton Blum, were instrumental in confirming this stereotype of the "insane martial spirit" of Imperial Japan, and the bigoted picture it would engender of the Japanese people as a whole.

[28] Author John M. Curatola wrote that the anti-Japanese sentiment probably played a role in the strategic bombing of Japanese cities,[29] which began on March 9/10, 1945, with the destructive Operation Meetinghouse firebombing of Tokyo to August 15, 1945, with the surrender of Japan.

[30] Sixty-nine cities in Japan lost significant areas and hundreds of thousands of civilian lives to firebombing and nuclear attacks from United States Army Air Forces B-29 Superfortress bombers during this period.

In 1943, Governor Warren signed a bill that expanded the Alien Land Law by denying the Japanese the opportunity to farm as they had before World War II.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the waning fortunes of heavy industry in the United States prompted layoffs and hiring slowdowns just as counterpart businesses in Japan were making major inroads into U.S. markets.

[citation needed] Futuristic period pieces such as Back to the Future Part II and RoboCop 3 frequently showed Americans as working precariously under Japanese superiors.

Author Michael Crichton took a break from science fiction to write Rising Sun, a murder mystery (later made into a feature film) involving Japanese businessmen in the U.S.

The fear of Japan became a rallying point for techno-nationalism,[clarification needed] the imperative to be first in the world in mathematics, science and other quantifiable measures of national strength necessary to boost technological and economic supremacy.

Japan's waning economic fortunes in the 1990s, known today as the Lost Decade, coupled with an upsurge in the U.S. economy as the Internet took off largely crowded anti-Japanese sentiment out of the popular media.