Anti-tobacco movement in Nazi Germany

In the early 20th century, German researchers found additional evidence linking smoking to health harms,[2][3][1] which strengthened the anti-tobacco movement in the Weimar Republic[4] and led to a state-supported anti-smoking campaign.

[18] The Nazi anti-tobacco campaign included banning smoking in trams, buses, and city trains,[1] promoting health education,[19] limiting cigarette rations in the Wehrmacht, organizing medical lectures for soldiers, and raising the tobacco tax.

[9] The 1880s invention of automated cigarette-making machinery in the American South made it possible to mass-produce cigarettes at low cost, and smoking became common in Western countries.

Critics of smoking organized the first anti-tobacco group in the country, named the Deutscher Tabakgegnerverein zum Schutze der Nichtraucher (German Tobacco Opponents' Association for the Protection of Non-smokers).

[24] After World War I, anti-tobacco movements continued in the German Weimar Republic, against a background of increasing medical research.

In the later years of World War II, researchers considered nicotine a factor behind the coronary heart failures suffered by a significant number of military personnel in the Eastern Front.

A pathologist of the Heer examined thirty-two young soldiers who had died from myocardial infarction at the front, and documented in a 1944 report that all of them were "enthusiastic smokers".

[33] In 1939, Franz H. Müller (a member of the National Socialist Motor Corps or NSKK, and the Nazi Party[34]) published a study reporting a higher prevalence of lung cancer among smokers.

Hans Reiter (the Reich Health Office president) was interned for two years and spent the rest of his career in private practice.

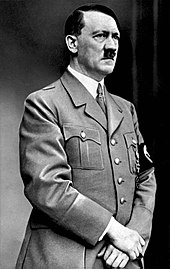

[28] He was unhappy because both Eva Braun and Martin Bormann were smokers and was concerned over Hermann Göring's continued smoking in public places.

[17] Hitler is often considered to be the first national leader to advocate nonsmoking; however, James VI and I, king of Scotland and England, was openly against smoking 330 years prior,[36] and the near-contemporary 1600s Chinese emperors Chongzhen and Kangxi both decreed the death penalty for smokers.

[40] Articles and a major medical book published in the 1930s observed an association between smoking (in both men and women) and lower fertility, including more miscarriages.

[40] Martin Staemmler [de], a prominent physician during the Nazi era, said that smoking by pregnant women resulted in a higher rate of stillbirths and miscarriages (a claim supported by modern research, for nicotine-using mothers, fathers, and their offspring[41][42]).

Werner Huttig of the Nazi Party's Rassenpolitisches Amt (Office of Racial Politics) said that a smoking mother's breast milk contained nicotine,[31] a claim that modern research has proven correct.

[49] Measures protecting non-smokers (especially children and mothers) from passive smoking were tied to the Nazi's desire for healthy young soldiers[35] and workers.

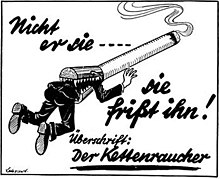

[9] The Nazis used several public relations tactics to convince the general population of Germany not to smoke, and gave variable support to non-officially-approved propaganda.

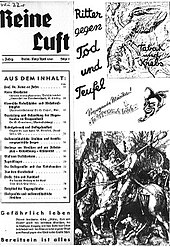

[55] Articles advocating nonsmoking were also published in the magazines Die Genussgifte (The Recreational Stimulants), Auf der Wacht (On the Guard) and Reine Luft (Clean Air).

[1][8] Karl Astel's Institute for Tobacco Hazards Research at Jena University purchased and distributed hundreds of reprints from Reine Luft.

[8] The magazine was published by tobacco control activists; it was later, in 1941, ordered by the propaganda ministry to moderate its tone and submit all material for pre-approval.

Some local measures were quite strict; for instance, one district department of the National Socialist Factory Cell Organization (NSBO) announced that it would expel female members who smoked publicly.

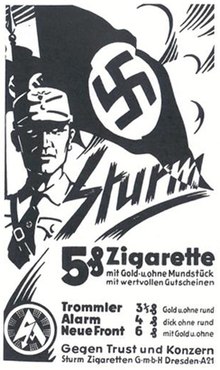

[1] They made unparalleled financial contributions to Nazi causes; the Sturmabteilung and other party organizations were repeatedly given six-figure sums, and the Hitler Youth were given an aircraft.

[38] The Nazi SA founded its own cigarette company, and violently promoted its own brands, breaking into stores that did not stock them and assaulting shopkeepers.

[17] Joseph Goebbels felt that cigarettes were essential to the war effort,[35] and (as propaganda minister) restricted anti-tobacco propaganda, arguing that anti-smoking campaigns were incompatible with free cigarettes being issued to millions serving in the military, legal tobacco advertising, and authority figures who smoked and denied the dangers of smoking.

[76][77] Generally, people who are already stressed, anxious, depressed, or otherwise suffering from poor moods become addicted more easily and find quitting more difficult.

As a result of the anti-tobacco measures implemented in the Wehrmacht (supply restriction, taxes, and propaganda),[1] the total tobacco consumption by soldiers decreased between 1939 and 1945.

[81] Tobacco-caused infertility[40] and hereditary damage (described in now-obsolete terms as "corrupt[ion]" of the "germ plasm") were considered problematic by the Nazis on the grounds that they harmed German "racial hygiene".

[49] During the opening ceremony of the aforementioned Wissenschaftliches Institut zur Erforschung der Tabakgefahren in 1941, Johann von Leers, editor of the Nordische Welt (Nordic World), proclaimed that "Jewish capitalism" was responsible for the spread of tobacco use across Europe.

Nazi-related rhetoric associating anti-smoking measures with fascism has been fairly widely used in nicotine marketing[9] (except in Germany, where such comparisons have brought strong reactions).

[8] At the end of the 20th century, the anti-tobacco campaign in Germany was unable to approach the level of the Nazi-era climax in the years 1939–41, and German tobacco health research was described by Robert N. Proctor as "muted".

[20] Modern Germany has some of Europe's least restrictive tobacco control policies,[8] and more Germans both smoke and die of it in consequence,[84][85] which also leads to higher public health costs.