Antinomianism

In some Christian belief systems, an antinomian is one who takes the principle of salvation by faith and divine grace to the point of asserting that the saved are not bound to follow the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments.

[20] Early Gnostic sects were accused of failing to follow the Mosaic Law in a manner that suggests the modern term "antinomian".

For example, the Manichaeans held that their spiritual being was unaffected by the action of matter and regarded carnal sins as being, at worst, forms of bodily disease.

Even the so-called Judaeo-Christian Gnostics (Cerinthus), the Ebionite (Essenian) sect of the Pseudo-Clementine writings (the Elkesaites), take up an inconsistent attitude towards Jewish antiquity and the Old Testament.

If the growing Christian Church, in quite a different fashion from Paul, laid stress on the literal authority of the Old Testament, interpreted, it is true, allegorically; if it took up a much more friendly and definite attitude towards the Old Testament, and gave a wider scope to the legal conception of religion, this must be in part ascribed to the involuntary reaction upon it of Gnosticism.

[23][a] Such deviations from the moral law were criticized by proto-orthodox rivals of the Gnostics, who ascribed various aberrant and licentious acts to them.

[17] The Lutheran Church benefited from early antinomian controversies by becoming more precise in distinguishing between law and gospel and justification and sanctification.

[26] As early as 1525, Johannes Agricola advanced his idea, in his commentary on Luke, that the law was a futile attempt of God to work the restoration of mankind.

"[27] Shortly after Melanchthon drew up the 1527 Articles of Visitation in June, Agricola began to be verbally aggressive toward him, but Martin Luther succeeded in smoothing out the difficulty at Torgau in December 1527.

But before the case could be brought to trial, Agricola left the city, even though he had bound himself to remain at Wittenberg, and moved to Berlin where he had been offered a position as preacher to the court.

[30] The Articles of the Church of England, Revised and altered by the Assembly of Divines, at Westminster, in the year 1643 condemns antinomianism, teaching that "no Christian man whatsoever is free from the obedience of the commandments which are called moral.

"[31] The Westminster Confession, held by Presbyterian Churches, holds that the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments "does forever bind all, as well justified persons as others, to the obedience thereof".

Such charges were frequently raised by Arminian Methodists, who subscribed to a synergistic soteriology that contrasted with Calvinism's monergistic doctrine of justification.

[38] Religious Society of Friends were charged with antinomianism due to their rejection of a graduate clergy and a clerical administrative structure, as well as their reliance on the Spirit (as revealed by the Inner Light of God within each person) rather than the Scriptures.

They also rejected civil legal authorities and their laws (such as the paying of tithes to the State church and the swearing of oaths) when they were seen as inconsistent with the promptings of the Inner Light of God.

Thus, the early Christian church incorporated ideas sometimes seen as partially antinomian or parallel to Dual-covenant theology, while still upholding the traditional laws of moral behavior.

(9) ...Peter went up upon the housetop to pray about the sixth hour: (10) And he became very hungry, and would have eaten: but while they made ready, he fell into a trance, (11) And saw heaven opened, and a certain vessel descending unto him, as it had been a great sheet knit at the four corners, and let down to the earth: (12) Wherein were all manner of fourfooted beasts of the earth, and wild beasts, and creeping things, and fowls of the air.

(Hebrews 7:12) The Apostle Paul, in his Letters, says that believers are saved by the unearned grace of God, not by good works, "lest anyone should boast",[55] and placed a priority on orthodoxy (right belief) before orthopraxy (right practice).

For example, the NIV translates these verses: "... he forgave us all our sins, having canceled the written code, with its regulations, that was against us and that stood opposed to us; he took it away, nailing it to the cross."

"[60] Andy Gaus' version of the New Testament translates this verse as: "Christ is what the law aims at: for every believer to be on the right side of [God's] justice.

Historically, this statement has been difficult for Protestants to reconcile with their belief in justification by faith alone as it appears to contradict Paul's teaching that works don't justify (Romans 4:1–8).

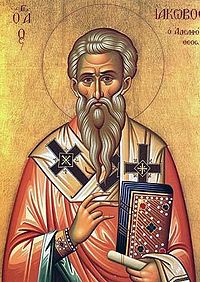

Martin Luther, believing that his doctrines were refuted by James's conclusion that works also justify, suggested that the Epistle might be a forgery, and relegated it to an appendix in his Bible.

But the scholar Alister McGrath says that James was the leader of a Judaizing party that taught that Gentiles must obey the entire Mosaic Law.

E. P. Sanders notes, "No substantial conflict existed between Jesus and the Pharisees with regard to Sabbath, food, and purity laws.

Several scholars argue that Matthew artificially lessened a claimed rejection of Jewish law so as not to alienate his intended audience.

Depending on the action, behavior, or belief in question, a number of different terms can be used to convey the sense of "antinomian": shirk ("association of another being with God"); bidʻah ("innovation"); kufr ("disbelief"); ḥarām ("forbidden"); etc.

[citation needed] As an example, the 10th century Sufi mystic al-Hallaj was executed for shirk for, among other things, his statement ana al-Ḥaqq (أنا الحق), meaning "I am the Truth".

Another individual who has often been termed antinomian is Ibn Arabi, a 12th and 13th-century scholar and mystic whose doctrine of waḥdat al-wujūd ("unity of being") has sometimes been interpreted as being pantheistic, and thus shirk.

One of these groups is the Nizārī Ismāʿīlī Shīʿa, who have always had strong millenarian tendencies arising partly from persecution directed at them by Sunnīs.

In his 1940 essay on Henry Miller, "Inside the Whale", the word appears several times, including one in which he calls A. E. Housman a writer in "a blasphemous, antinomian, 'cynical' strain", meaning defiant of arbitrary societal rules.