Antiochus XI Epiphanes

Following the murder of Seleucus VI, Antiochus XI declared himself king jointly with his twin brother Philip I. Dubious ancient accounts, which may be contradicted by archaeological evidence, report that Antiochus XI's first act was to avenge his late brother by destroying Mopsuestia in Cilicia, the city responsible for the death of Seleucus VI.

In 93 BC, Antiochus XI took Antioch, an event not mentioned by ancient historians but confirmed through numismatic evidence.

The conflict between the brothers would last a decade and a half;[12] it claimed the life of Tryphaena and ended with the assassination of Antiochus VIII at the hands of his minister Herakleon of Beroia in 96 BC.

[20] In the aftermath of Seleucus VI's death, Antiochus XI and Philip I declared themselves kings in 94 BC; the historian Alfred Bellinger suggested that their base was a coastal city north of Antioch,[21] while Arthur Houghton believed it was Beroea, because the city's rulers were Philip I's allies.

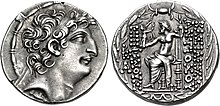

On all jugate coins, Antiochus XI was portrayed in front of Philip I, his name taking precedence,[24] showing that he was the senior monarch.

According to Josephus, Antiochus XI became king before Philip I, but the numismatic evidence suggests otherwise, as the earliest coins show both brothers ruling jointly.

[note 1][34] The beard sported by Antiochus XI on his jugate coins from Tarsus is probably a sign of mourning and the intention to avenge Seleucus VI's death.

[note 2] The ruler's portrait express tryphé (luxury and magnificence), where his unattractive features and stoutness are emphasized.

Most late Seleucid monarchs, including Antiochus XI, spent their reigns fighting, causing havoc in their lands.

[10] Eusebius's statement is doubtful because in 86 BC, Rome conferred inviolability upon the cult of Isis and Sarapis in Mopsuestia, which is proven by an inscription from the city.

[28] The 6th-century Byzantine monk and historian John Malalas, whose work is considered generally unreliable by scholars,[46] mentions the reign of Antiochus XI in his account of the Roman period in Antioch.

[47] The material evidence for Antiochus XI's success in taking the capital was provided in 1912, when an account of a coin struck by him in Antioch was published.

Eusebius failed to note the reign of Antiochus XI in Antioch, stating that the final battle took place immediately after the destruction of Mopsuestia; a statement contradicted by numismatic evidence.