Antiochus X Eusebes

Eusebes lived during a period of general disintegration in Seleucid Syria, characterized by civil wars, foreign interference by Ptolemaic Egypt and incursions by the Parthians.

Modern scholars prefer the account of Josephus and question practically every aspect of the versions presented by other ancient historians.

Numismatic evidence shows that Antiochus X was succeeded in Antioch by Demetrius III, who controlled the capital in c. 225 SE (88/87 BC).

The second century BC witnessed the disintegration of the Syria-based Seleucid Empire due to never-ending dynastic feuds and foreign Egyptian and Roman interference.

[23] Aradus was an independent city since 137 BC, meaning that Antiochus X made an alliance with it, since he would not have been able to subdue it by force at that stage of his reign.

Appian commented that he thought the real reason behind the epithet "Eusebes" to be a joke by the Syrians, mocking Antiochus X's piety, as he showed loyalty to his father by bedding his widow.

[29] One of Antiochus X's first actions was to avenge his father;[33] in 94 BC, he advanced on the capital Antioch and drove Seleucus VI out of northern Syria into Cilicia.

[39] Now Antiochus X ruled northern Syria and Cilicia;[37] around this time, Mopsuestia minted coins with the word "autonomous" inscribed.

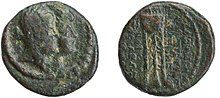

[40] In the view of the numismatist Hans von Aulock [de], some coins minted in Mopsuestia may carry a portrait of Antiochus X.

[note 6][47] Philip I was probably centered at Beroea; his brother, Demetrius III, who ruled Damascus, supported him and marched north probably in the spring of 93 BC.

[67][50] Antiochus X's end as told by Josephus, which has the king killed during a campaign against the Parthians, is considered the most reliable and likely by modern historians.

[68][65] Towards the end of his reign, Antiochus X increased his coin production, and this could be related to the campaign undertaken by the Seleucid monarch against Parthia, as recorded by Josephus.

The Parthians were advancing in eastern Syria in the time of Antiochus X, which would have made it important for the king to counterattack, thus strengthening his position in the war against his cousins.

[69] The majority of scholars accept the year 92 BC for Antiochus X's end:[50][70] No known coins issued by the king in Antioch contain a date.

[50] On the other hand, in the year 221 SE (92/91 BC), the city of Antioch issued civic coinage mentioning no king;[50] Hoover noted that the civic coinage mentions Antioch as the "metropolis" but not as autonomous, and this might be explained as a reward from Antiochus X bestowed upon the city for supporting him in his struggle against his cousins.

[note 8][50] In 2007, using a methodology based on estimating the annual die usage average rate (the Esty formula), Hoover proposed the year 224 SE (89/88 BC) for the end of Antiochus X's reign.

[77] The historian Marek Jan Olbrycht [pl] considered Hoover's dating and arguments too speculative, as they contradict ancient literature.

[67] Kuhn considered a confusion between father and son to be out of the question because Appian mentioned the epithet Eusebes when talking about the fate of Antiochus X.

In the view of Kuhn, Antiochus X retreated to Cilicia after being defeated by Tigranes II, and his sons ruled that region after him and were reported visiting Rome in 73 BC.

[85] However, numismatic evidence proves that Demetrius III controlled Cilicia following the demise of Antiochus X, and that Tarsus minted coins in his name c. 225 SE (88/87 BC).

[74] In 1949, a jugate coin of Cleopatra Selene and Antiochus XIII, from the collection of the French archaeologist Henri Arnold Seyrig, was dated by the historian Alfred Bellinger to 92 BC and ascribed to Antioch.

[67] Based on Bellinger's dating, some modern historians, such as Ehling, proposed that Cleopatra Selene enjoyed an ephemeral reign in Antioch between the death of her husband and the arrival of his successor.