Antisemitism in the Russian Empire

Before the 18th century, Russia maintained an exclusionary policy towards Jews, in accordance with the anti-Jewish precepts of the Russian Orthodox Church.

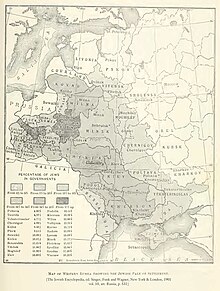

[3] In 1772, Catherine II forced the Jews of the Pale of Settlement to stay in their shtetls and forbade them from returning to the towns that they occupied before the partition of Poland.

[6][7][8][9][10] In Jewish diasporal communities hailing from the Russian Empire, the 19th century is often recalled as a time where Jews were forced to the front lines of the army and used as "cannon fodder".

[6] The Crimean War led to an increased kidnapping of Jewish male children and young men to fight on the front.

These arose from a variety of motivations, not all of them related to Christian antisemitism, which derived from the notion that Jews were responsible for the crucifixion of Jesus.

[15] The first pogrom is often considered to be the 1821 anti-Jewish riots in Odessa (modern Ukraine) after the death of the Greek Orthodox Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople, in which 14 Jews were killed.

[16] The virtual Jewish encyclopedia claims that initiators of 1821 pogroms were the local Greeks that used to have a substantial diaspora in the port cities of what was known as Novorossiya.

This event was blamed on the Jews and sparked widespread anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire, which lasted for three years, from 27 April 1881 to 1884.

The Tsar's minister Konstantin Petrovich Pobedonostsev stated the aim of the government with regard to the Jews was that "One third will die out, one third will leave the country and one third will be completely dissolved in the surrounding population".

Between 1881 and the outbreak of the First World War, an estimated 2.5 million Jews left Russia - one of the largest group migrations in recorded history.

[12] Jan Gotlib Bloch (1836-1901) a wealthy railroad magnate and researcher on warfare and society converted to Calvinism, the religion of a small minority in the Russian Empire.

Following the wave of pogroms of the 1880s and the early 1890s, a commission headed by the vociferously antisemitic Interior Minister Vyacheslav von Plehve recommended a further worsening of the Jews' legal position.

The result, completed only in 1901 - one year before Bloch's death - was a five-volume work entitled "Comparison of the material and moral levels in the Western Great-Russian and Polish Regions".

On the basis of extensive statistical data, compiled mainly in the Pale of Settlement, he gave a comprehensive account of the Jewish role in the Empire's economic life, in crafts, trade and industry.

The study showed that the Jews were a boon to the Russian economy - rather than damaging and threatening it, as was at the time regularly claimed by antisemites.

[26] In the second half of the 19th century, in response to the widespread and systematic persecution of Jews, many Jews fled the Russian Empire, but with the spread of literacy, many of those who stayed were drawn into radical and reformist ideologies, attracted by the prospect of liberation of Jewish communities from the conditions imposed on them, as well as disgust at the political system of the Russian Empire.

[12] The same period saw the Bundist and Zionist movements emerge and rapidly grow, with their promises to end the persecution of Jews, but their growth led to a polarization of Jewish communities due to their diverging political goals.

While the Bundists proclaimed the superiority of the Yiddish language, the Zionists promoted Hebrew as a lingua franca for Jews of varying geographic origins.

[12] While the Bundists saw the home for Russian Jewry in Russia, the Zionists aimed to establish a Jewish state free of rule by foreigners.

[12] The Bundists, on the other hand, proclaimed Yiddish as a national language for Jews and argued for a separate set of Jewish-run schools.

[28][29] Led by Oscar Straus, Jacob Schiff, Mayer Sulzberger, and Rabbi Stephen Samuel Wise, they organized protest meetings, issued publicity, and met with President Theodore Roosevelt and Secretary of State John Hay.

Stuart E. Knee reports that in April, 1903, Roosevelt received 363 addresses, 107 letters and 24 petitions signed by thousands of Christians leading public and church leaders--they all called on the Tsar to stop the persecution of Jews.

[12] However, only a few months after its foundation, the provisional government was overthrown by the Bolsheviks in the October Revolution, and in the ensuing anarchy, violent antisemitism returned to Russia, with sporadic pogroms.