Antonio López de Santa Anna

Santa Anna was also known for his ostentatious and dictatorial style of rule, making use of the military to dissolve Congress multiple times and referring to himself by the honorific title of His Most Serene Highness.

Historians debate the exact number of his presidencies, as he would often share power and make use of puppet rulers; biographer Will Fowler gives the figure of six terms[7] while the Texas State Historical Association claims five.

[9] Santa Anna's legacy has subsequently come to be viewed as profoundly negative, with historians and many Mexicans ranking him as "the principal inhabitant even today of Mexico's black pantheon of those who failed the nation".

His paternal uncle, Ángel López de Santa Anna, was a public clerk (escribano) and became aggrieved when the town council of Veracruz prevented him from moving to Mexico City to advance his career.

Since the late 18th-century Bourbon Reforms, the Spanish crown had favored peninsular-born Spaniards over American-born; young Santa Anna's family was affected by the growing disgruntlement of creoles whose upward mobility was thwarted.

[12][13] Santa Anna's mother favored her son's choice of a military career, supporting his desire to join the Spanish Army, rather than be a shopkeeper as his father preferred.

[14] Santa Anna's origins on Mexico's eastern coast had important ramifications for his military career, as he had developed immunity from yellow fever, endemic to the region.

Over his career, Santa Anna was a populist caudillo, a strongman wielding both military and political power, similar to others who emerged in the wake of Spanish American wars of independence.

[22] Iturbide, now Emperor Augustin I, rewarded Santa Anna with the command of the vital port of Veracruz, the gateway from the Gulf of Mexico to the rest of the nation and site of a customs house.

[26] No longer the main player in the movement against Iturbide or the creation of new political arrangements, Santa Anna sought to regain his position as a leader and marched forces to Tampico, then to San Luis Potosí, proclaiming his role as the "protector of the federation".

The so-called Montaño rebellion in December 1827 called for the prohibition of secret societies, implicitly meaning liberal York Rite Freemasons, and the expulsion of U.S. diplomat Joel Roberts Poinsett, a promoter of federal republicanism.

Even before all the votes had been counted, Santa Anna raised a rebellion and called for the nullification of the election results, as well for a new law expelling Spanish nationals who he believed to have been in league with the conservatives.

Three months later, in December 1829, Vice-president Anastasio Bustamante, a conservative, mounted a successful coup d'etat against President Guerrero, who left Mexico City to lead a counter-rebellion in the south.

[40] The government soon issued a law, the Ley del Caso, which called for the arrest of 51 politicians, including Bustamante, for holding "unpatriotic" beliefs and their expulsion from the country.

[46] "The santanistas [supporters of Santa Anna] succeeded in achieving what the radicals had failed to do: forcing the Church to assist the republic's daily fiscal needs with its funds and properties.

[50] The New York Post editorialized that "had Santa Anna treated the vanquished with moderation and generosity, it would have been difficult if not impossible to awaken that general sympathy for the people of Texas which now impels so many adventurous and ardent spirits to throng to the aid of their brethren.

"[51] The Zacatecas militia, the largest and best supplied of the Mexican states, led by Francisco García Salinas, was well armed with .753 caliber British 'Brown Bess' muskets and Baker .61 rifles.

In an 1874 letter, Santa Anna asserted that killing the defenders of Alamo was his only option, stressing that Texan commander William B. Travis was to blame for the degree of violence during the battle.

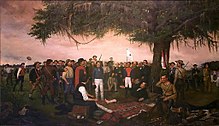

The day after the battle, a small Texan force led by James Austin Sylvester captured Santa Anna near a marsh; the general had hastily dressed himself in a dead Mexican dragoon's uniform but was quickly recognized.

Santa Anna engaged the French at Veracruz but was forced to retreat after a failed assault, sustaining injuries in his left leg and hand by cannon fire.

At Contreras, Mexican General Gabriel Valencia, an old political and military rival of Santa Anna's, did not recognize his authority as supreme commander and disobeyed his orders as to where his troops should be placed.

In April 1853, he was invited to return to Mexico by conservatives who had overthrown a weak liberal government, initiated under the Plan de Hospicio, drawn up by the clerics in the cathedral chapter of Guadalajara.

He honored his promises to the church, revoking a decree denying protection for the fulfillment of monastic vows, a reform promulgated twenty years earlier by Gómez Farías.

[74] A group of liberals including Alvarez, Benito Juárez, and Ignacio Comonfort overthrew Santa Anna under the Plan of Ayutla, which called for his removal from office.

Calderón de la Barca observed that "After breakfast, the Señora having dispatched an officer for her cigar-case, which was gold with a diamond latch, offered me a cigar, which I having declined, she lighted her own, a little paper 'cigarette', and the gentlemen followed her good example.

[82] In 1865, Santa Anna attempted to return to Mexico and offer his services during the French invasion, seeking once again to play the role as the country's defender and savior, only to be refused by Juárez.

Later that year a schooner owned by Gilbert Thompson, son-in-law of Daniel Tompkins, brought Santa Anna to his home in Staten Island,[83] where he tried to raise money for an army to return and take over Mexico City.

In 1874, Santa Anna took advantage of a general amnesty issued by President Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada and returned to Mexico, by then crippled and almost blind from cataracts.

[84] But as a military leader, Gates Brown, a historian at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College, considers Santa Anna among history's worst for his mistakes in two wars which cost Mexico much of its territory.

At Cerro Gordo he dismissed suggestions from Manuel Robles Pezuela, one of his officers, that he reinforce the Atalaya hill's defenses, believing the terrain made that unnecessary.