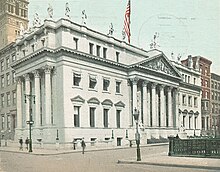

Appellate Division Courthouse of New York State

The Appellate Division Courthouse is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, and its facade and interior are both New York City designated landmarks.

The Appellate Division Courthouse is in the Flatiron District neighborhood of Manhattan in New York City, on the northeast corner of the intersection of Madison Avenue and 25th Street.

[4][5] It was designed by James Brown Lord in an Italian Renaissance Revival style with Palladian-inspired details,[8] which include tall columns, a high base, and flat walls.

[4] The structure has been likened to an 18th-century English country house because of its Palladian details,[2][9] and it was similar in scale to low-rise residential buildings at the time of its construction.

[16][17][18] According to the New York City Department of Citywide Administrative Services, at the time of the building's construction, it featured decorations by more sculptors than any other edifice in the United States.

[25] Although members of the then-prominent Tammany Hall political ring had advocated for the inclusion of sculptures of living people, the artists were against the idea of "a number of pants statues, which at a distance would have looked alike".

[31][7] At street level, "two pedestals holding two monumental seated figures"[12] of Wisdom and Force, by Frederick Ruckstull, flank a set of stairs leading to the portico.

[40] Thomas Shields Clarke sculpted a group of four female caryatids on the Madison Avenue front, at the third-floor level, representing the seasons.

[9][45] These statues are of the same height and proportion, are robed, and appear with various attributes associated with the law, such as book, scroll, tablet, sword, charter, or scepter.

[35][44][48] Charles Albert Lopez's Mohammed originally stood on the western end of the 25th Street elevation[36][49] but was removed in 1955 following protests against the image of the prophet from Muslim nations.

[13][67] The Baltimore Sun wrote that the courthouse was "the only public building in the United States that from the beginning was designed with a view to complete harmony of detail—architectural, mural decoration and sculptural effect".

[68] The main hall measures 50 by 38 feet (15 by 12 m) across[69] and functions as a lobby and waiting area, with leather-and-wood seats designed by the Herter Brothers.

[68] The north wall of the main hall contains a pair of staircases with openwork railings made of bronze; the stairs lead to the second and third floors.

[81] Above the stained-glass windows on the south wall is a Latin inscription that translates to "Civil Law should be neither influenced by good nature, nor broken down by power, nor debased by money.

[22] The circumference of the dome contains wrought letters spelling out the names of "past leaders of the American bar" at the time of the building's completion in 1899.

[71] Placed on the western half of the ground floor, near Madison Avenue, are the judges' chambers and other rooms,[80] including clerks' and stenographers' offices.

[81] In June 1895, the New York City Sinking Fund Commission approved the Appellate Division's request to rent the third floor of the Constable Building at 111 Fifth Avenue, at the intersection with 19th Street, for two years.

The New York City Bar Association was developing its own building on part of the depot site, and the remainder of the lot would have accommodated the court's 50,000-volume library easily.

[10] James Brown Lord was hired to design a three-story marble courthouse at a cost of $650,000, with various allegorical statues and porticoes on Madison Avenue and 25th Street.

[22] Work on the courthouse was nearly complete when, on December 20, 1899, Lord invited a small group of guests, including Appellate Division justices and their friends, to tour the interior.

[119] Mayor Fiorello La Guardia proposed converting the Appellate Division Courthouse into a municipal art center that presented theatrical performances.

[131] In late 1950, the city's public works commissioner Frederick Zurmuhlen approved an $800,000 plan by architecture firm Rogers & Butler to erect a six-story annex to the courthouse.

Zurmuhlen also planned to install a steam-and-warm-air heating plant in the existing courthouse, replace the masonry and stone on the facade, add air-conditioning to part of the interior, and repair the roof.

[142] As part of the agreement, the Merchandise Mart's developer Samuel Rudin agreed to pay out $3.45 million to the New York City government over 75 years.

[145] The interior of the courthouse was designated a New York City landmark in 1981,[5][4] and the entire building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1982.

[12] The New-York Tribune wrote that the building "will have no peer, it is confidently believed, even among the imposing-looking courts of justice which the Old World is able to present".

[12][23] DeKay believed that the small size of the Madison Avenue frontage gave the appearance that the building was "part of a larger structure".

[89] Richard Ladegast wrote for Outlook that Lord should be "complimented upon his good taste in building, as it were, a frame for some fine pictures and a pedestal for not a few imposing pieces of sculpture".

[153] Writing about that show, architectural critic Ada Louise Huxtable wrote in The New York Times that the building was "a compendium of classical culture backed up against the featureless glass facade of a recent office tower", the Merchandise Mart.

[153] Another New York Times columnist likened the interiors to the "residence of a Middle Western industrialist",[154] while yet another reporter for that paper described the edifice as a "small marble palace".