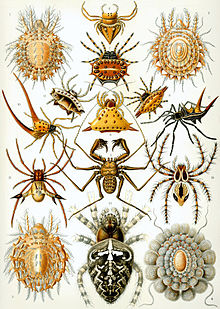

Arachnid

[3][4] The term is derived from the Greek word ἀράχνη (aráchnē, 'spider'), from the myth of the hubristic human weaver Arachne, who was turned into a spider.

While the term cephalothorax implies a fused cephalon (head) and thorax, there is currently neither fossil nor embryological evidence that arachnids ever had a separate thorax-like division.

It is typically divided into a preabdomen and postabdomen, although this is only clearly visible in scorpions, and in some orders, such as the mites, the abdominal sections are completely fused.

[15] Like all arthropods, arachnids have an exoskeleton, and they also have an internal structure of cartilage-like tissue, called the endosternite, to which certain muscle groups are attached.

This type of tracheal system has almost certainly evolved from the book lungs, and indicates that the tracheae of arachnids are not homologous with those of insects.

The diet of mites also include tiny animals, fungi, plant juices and decomposing matter.

[33][34] Arachnids produce digestive enzymes in their stomachs, and use their pedipalps and chelicerae to pour them over their dead prey.

The digestive juices rapidly turn the prey into a broth of nutrients, which the arachnid sucks into a pre-buccal cavity located immediately in front of the mouth.

The lateral ocelli evolved from compound eyes and may have a tapetum, which enhances the ability to collect light.

The most important to most arachnids are the fine sensory hairs that cover the body and give the animal its sense of touch.

[35] Complex courtship rituals have evolved in many arachnids to ensure the safe delivery of the sperm to the female.

[38][39] The phylogenetic relationships among the main subdivisions of arthropods have been the subject of considerable research and dispute for many years.

A consensus emerged from about 2010 onwards, based on both morphological and molecular evidence; extant (living) arthropods are a monophyletic group and are divided into three main clades: chelicerates (including arachnids), pancrustaceans (the paraphyletic crustaceans plus insects and their allies), and myriapods (centipedes, millipedes and allies).

[42] Including fossil taxa does not fundamentally alter this view, although it introduces some additional basal groups.

[45] Chelicerata (sea spiders, horseshoe crabs and arachnids) Myriapoda (centipedes, millipedes, and allies) Pancrustacea (crustaceans and hexapods) The extant chelicerates comprise two marine groups: Sea spiders and horseshoe crabs, and the terrestrial arachnids.

[47] Pycnogonida (sea spiders) Xiphosura (horseshoe crabs) Arachnida Discovering relationships within the arachnids has proven difficult as of March 2016[update], with successive studies producing different results.

A study in 2014, based on the largest set of molecular data to date, concluded that there were systematic conflicts in the phylogenetic information, particularly affecting the orders Acariformes, Parasitiformes and Pseudoscorpiones, which have had much faster evolutionary rates.

Analyses of the data using sets of genes with different evolutionary rates produced mutually incompatible phylogenetic trees.

The authors favoured relationships shown by more slowly evolving genes, which demonstrated the monophyly of Chelicerata, Euchelicerata and Arachnida, as well as of some clades within the arachnids.

The diagram below summarizes their conclusions, based largely on the 200 most slowly evolving genes; dashed lines represent uncertain placements.

[50][51] Genetic analysis has not yet been done for Ricinulei, Palpigradi, or Solifugae, but horseshoe crabs have gone through two whole genome duplications, which gives them five Hox clusters with 34 Hox genes, the highest number found in any invertebrate, yet it is not clear if the oldest genome duplication is related to the one in Arachnopulmonata.

[52] Pycnogonida †Chasmataspidida †Eurypterida Parasitiformes Acariformes Pseudoscorpiones Opiliones Palpigradi Solifugae Ricinulei Xiphosura Scorpiones †Trigonotarbida Araneae †Uraraneida †Haptopoda Amblypygi Schizomida Uropygi More recent phylogenomic analyses that have densely sampled both genomic datasets and morphology have supported horseshoe crabs as nested inside Arachnida, suggesting a complex history of terrestrialization.

However, molecular phylogenetic studies suggest that the two groups do not form a single clade, with morphological similarities being due to convergence.