Arch of Constantine

The arch was commissioned by the Roman Senate to commemorate Constantine's victory over Maxentius at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge in AD 312.

Situated between the Colosseum and the Palatine Hill, the arch spans the Via Triumphalis, the route taken by victorious military leaders when they entered the city in a triumphal procession.

This route started at the Campus Martius, led through the Circus Maximus, and around the Palatine Hill; immediately after the Arch of Constantine, the procession would turn left at the Meta Sudans and march along the Via sacra to the Forum Romanum and on to the Capitoline Hill, passing through both the Arches of Titus and Septimius Severus.

During the Middle Ages, the Arch of Constantine was incorporated into one of the family strongholds of ancient Rome, as shown in the painting by Herman van Swanevelt, here.

By the time of his accession in 306 Rome was becoming increasingly irrelevant to the governance of the empire, most emperors choosing to live elsewhere and focusing on defending the fragile boundaries, where they frequently founded new cities.

In contrast to his predecessors, Maxentius concentrated on restoring the capital; his epithet was conservator urbis suae (preserver of his city).

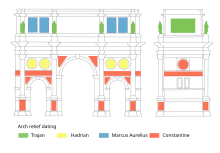

[5] The contrast between the styles of the re-used Imperial reliefs of Trajan, Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius and those newly made for the arch is dramatic and, according to Ernst Kitzinger, "violent",[18] that where the head of an earlier emperor was replaced by that of Constantine the artist was still able to achieve a "soft, delicate rendering of the face of Constantine" that was "a far cry from the dominant style of the workshop".

Kitzinger compares a roundel of Hadrian lion-hunting, which is "still rooted firmly in the tradition of late Hellenistic art", and there is "an illusion of open, airy space in which figures move freely and with relaxed self-assurance" with the later frieze where the figures are "pressed, trapped, as it were, between two imaginary planes and so tightly packed within the frame as to lack all freedom of movement in any direction", with "gestures that are "jerky, overemphatic and uncoordinated with the rest of the body".

[18] In the 4th century reliefs, the figures are disposed geometrically in a pattern that "makes sense only in relation to the spectator", in the largesse scene (below) centred on the emperor who looks directly out to the viewer.

Faces are cut rather than modeled, hair takes the form of a cap with some superficial stippling, drapery folds are summarily indicated by deeply drilled lines.

[20]The commission was clearly highly important, if hurried, and the work must be considered as reflecting the best available craftsmanship in Rome at the time; the same workshop was probably responsible for a number of surviving sarcophagi.

[24] One factor that cannot be responsible, as the date and origin of the Venice Portrait of the Four Tetrarchs show, is the rise of Christianity to official support, as the changes predated that.

As it celebrates the victory of Constantine, the new "historic" friezes illustrating his campaign in Italy convey the central meaning: the praise of the emperor, both in battle and in his civilian duties.

[24] As yet another possible reason, it has often been suggested that the Romans of the 4th century truly did lack the artistic skill to produce acceptable artwork, and were aware of it, and therefore plundered the ancient buildings to adorn their contemporary monuments.

From the same time period the two large (3 m high) panels decorating the attic on the east and west sides of the arch show scenes from Trajan's Dacian Wars.

The horizontal frieze below the round reliefs are the main parts from the time of Constantine,[5] running around the monument, one strip above each lateral archway and including the west and east sides of the arch.

It continues on the southern, face, with the Siege of Verona (Obsidio) on the left (South west), an event which was of great importance to the war in Northern Italy.

On the right (South east) is depicted the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (Proelium) with Constantine's army victorious and the enemy drowning in the river Tiber.

It reads thus, identically on both sides (with abbreviations completed in parentheses): The words instinctu divinitatis ("inspired by the divine") have been greatly commented on.

In this situation, the vague wording of the inscription can be seen as the attempt to please all possible readers, being deliberately ambiguous, and acceptable to both pagans and Christians.