Archaeology of Oman

), though its prehistoric remains differ in some respects from the more specifically defined Oman proper, which corresponds roughly with the present-day central provinces of the Sultanate.

Ages, on the other hand, are on a much larger scale; they are conventional, but difficult to date absolutely—partially due to different rates of regional development.

The absolute dates for the different periods are still under study and it is difficult to assign years to the Late Iron Age of central and southern Oman.

Theories state that the Nubian Tool Complex (c. 128,000-74,000 years ago) spread from Africa to the Arabian Peninsula during the Late Pleistocene, via the Red Sea.

[3] The Neolithic Age coincides with the beginning of the Holocene and sees the advent of a food producing, or agricultural, society, as opposed to hunting and gathering; it ranges loosely from about 10,000-3,500 BCE.

[5] In 2010, the French Mission of Adam located Jabal al-'Aluya; an in-land site with 127 structural remains of varying shapes and compositions, supposed to be hut-like dwellings, hearths, and graves—similar to those discussed above.

[6] A site named Al-Dahariz 2, located in the Dhofar governance, has been found to contain fluted-point lithics—a form before thought to be unique to the Americas.

The fluted technology has a large, linear chunk taken out from the bottom or top of the lithic, creating a lighter projectile that can keep its sharpness.

Copper smelting began perhaps at al-Batina,[9] however such ores would leave little slag and the process did not require special conditions, so there would be little to indicate its presence in the archaeological record.

[8] During this age, metal production increased considerably in relation to that of the preceding Hafit Period, with several plano-convex copper ingots, weighing 1–2 kg, being found.

[8] In 1982, a potsherd attributed to the Indus Valley Civilization was found at Ras al-Jinz, located at the easternmost point of the Arabian Peninsula.

[10][14] Also found there, were pieces of bitumen impressed with what appeared to be ropes, reed mats, and wood planks, with a few of the fragments still housing barnacles; implying it was caulking for an early boat.

One scholar in particular offered concrete argumentation for a gradual transition as a model from the Early to Late Iron Ages at certain sites in Central Oman.

Usually hand-made and hard-fired, the pottery from the Lizq fort is most similar to that from the latest Early Iron Age sites at al-Moyassar (or al-Maysar) and Samad al-Shan.

The inhabitants must have considered their society to be a safe one since they built such visible and vulnerable free-standing tombs with poor chances of survival and as a ready source of building materials have rapidly disappeared since 1980.

[23] In November, 2019, 45 well-preserved tombs covering a 50-80 square metre area and a settlement, dating back to beginning of the Iron Age, were discovered in Al-Mudhaibi by archaeologists from Oman and Heidelberg University.

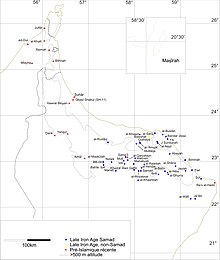

Samad LIA sites scatter over an estimated 17,000 km2 (6,600 sq mi) bordered to the west in Izkī, to the north in the capital area, to the south Jaʿlān, and to the east at the coast.

Samad al-Shan and smaller sites, such as al-Akhdhar, al-Amqat, Bawshar[28] and al-Bustan, are type-sites for this non-writing population, with mostly hand-made pottery, copper-alloy, and iron artefacts.

Reoccurring pottery wares and shapes, small finds, as well as a few grave structure types define the Samad Late Iron Age assemblage.

They contain flexed skeletons, with the men usually are placed on the right side and the women usually on the left, their heads generally point toward the south-east.

Persian Achaemenid, Parthian, and Sasanian dominance of Oman is firmly entrenched in the secondary literature; thus, it is easy to criticize the integrity of the definition of the Samad assemblage.

Parthian, and later Sasanian, invaders from Iran temporarily dominated certain towns[31] politically and militarily, but for logistical reasons, it was only possible to occupy a few sites, as occurred during later invasions.

The tribal grounds of the Azd tribes in south-eastern Arabia of course are far larger and more diverse than the area of the Samad Late Iron Age sites.

On the other hand, Dr. Fleitmann has studied stalagmites from al-Hutah Cave in central Oman and has gathered information for a series of megadroughts especially around 530 CE.

[35] Several Late Iron Age sites do not link in terms of form and details of manufacture of their artifacts with the Samad characteristic assemblage.

[38] The term megalith has been used and misused in a wide variety of meanings; triliths found in Oman differ from ones in Europe in size and shape.

[40][41][42][43] To judge from Mehra place-names and the triliths, Mahri speakers lived further to the north until Bedouin tribes pushed them into the south.

[49] Various survey and a few excavations have shed light on the archaeology of the South Province of the Sultanate;[50] the largest and best-known site is Khor Rori, a trading fort established by the Hadhramite kingdom in the 3rd century BCE.

[52] The type of sherd depicted was for many years considered to be Late Iron Age, but recent research re-dates it to the medieval period.

Very little archaeological evidence from the early Islamic Age exists; the earliest building structures which survive date to medieval times.