Archaic Greek sculpture

[5] There is evidence of human presence in the region now known as Greece – including the continental portion and the islands – since the Paleolithic, and in those early times their artifacts amounted to simple stone and bone tools and weapons, and pottery.

Statuettes in marble and alabaster survive from Cycladic art, some reaching large dimensions, mostly representing female deities with their arms folded across their chests, but there are also male specimens and others in various positions, pieces that became famous and eagerly collected for their highly stylized forms that remind us a little of modern sculpture.

What has come down to us of its sculpture are small statues, of which the Minoan snake goddess figurines, mostly in faience, found in the royal palace of Knossos, and the Palaikastro Kouros, in ivory, gold, stone and rock crystal, are famous, but it is possible that larger works in wood were also produced.

For reasons not yet fully elucidated, the local population declined drastically, the economy collapsed, writing ceased to be practised, the arts regressed, and the repertoire of figurative representation disappeared almost completely.

[15] Its sculpture was probably influenced by the art of the invading peoples, who brought with them an analytical tendency to design the works in distinct sections and in essential forms, being almost only silhouettes – a triangle for the torso, a circle for the head, and so on.

Literature experienced a resurgence and found its first great exponents in Hesiod and Homer, and philosophy researched new ways to understand the world and man under a rationalist viewpoint, in which supernatural explanations for the phenomena of nature were abandoned in search of more scientific causes.

[3] The process of formation of the city-state required a more consistent social organization than that maintained in the ancient villages, hamlets and scattered demes, which functioned under the direction of a leader, king or chief magistrate, the basileus, and to consolidate this new political union it was necessary that the centralized power be divided among a group of aristocrats, aided by bureaucrats, in a sharing of responsibilities that laid the first foundations of the future democracy.

From there, Greek craftsmen learned to produce terracotta reliefs in series from molds, a practice that defined stereotyped formal solutions for the representation of the human figure that would become the basis for the organization of full-figure statuary as well.

The scheme of these works was strictly standardized, homogenizing the entire production of figurative sculpture and eliminating all traces of creative freedom and naturalism found in the statues of the times of the Egyptian cultures.

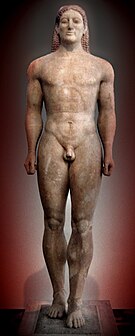

The bodies assume a hieratic posture, in a frontal position, arms hanging down at their sides or one folded at the chest, one leg in advance suggesting movement, with long curly hair and facial expression fixed in a smile outline.

The chronology of the works is uncertain and dates are generally approximate, because the evolution of form was fairly homogeneous throughout Greece, without the emergence of significantly differentiated regional schools, and all innovations was quickly adopted by all centers of production.

[33][34] This impersonality is explained, according to Jeffrey Hurwit, because in the Archaic world the main goal of the sculptor was to offer a convincing, rather than realistic, piece, for the most constant and pressing impulse of this art "was to formalize, to define general patterns, to recreate nature in an intelligible form," consistent with the formalist and hierarchical principles of the cultured aristocracy that commissioned these works.

[35] At the same time, the naked kouros became a significant typology because the public nudity of the warrior and athlete became socially accepted in certain situations, and an identification began between physical beauty and the collection of moral values known as arete, in a broad concept called kalos kagathos.

When an athlete won a contest in the Games, the greatest of the Hellenic gatherings, his or her consecration was vested with a transcendent meaning and raised the man to the level of the divine, evoking, as we read in Pindar, the feats of the gods and heroes.

In any case, their type is clearly Apollonian, illustrating an ideal of youth and beauty, and for this reason it is also licit to assume that they were at least in part erotic representations, for in addition to Apollo's having had in the myth several homosexual relationships, the statues bear the features desirable in a man of that time – broad shoulders, strong buttocks and thighs, thin waist, and small penis – in a male-dominated society that had institutionalized pederasty as an honorable practice, imbued with educational values.

The representation of dresses and sophisticated hairstyles offered yet another field for the sculptor to find diversified decorative solutions and multiple surface treatments, exploring graphics, textures, and transparency effects.

[38] While the kouroi illustrate the conceptions and ideals of the male world, the korai offer a sensitive portrait of the values prized in the women of Archaic society – good taste revealed in the use of clothing, jewelry, and sophisticated hairstyles, and youth, beauty, and health as symbols of the ability to bear children – and also indirectly indicated the wealth of the man with whom they were associated, giving a measure of who she was and how she was perceived in her group.

The new Greek temple gave rise to narrative group scenes, unheard of in its time, favored anatomical and kinesiological research, created new challenges for the conception of sets, stimulated the exploration of light and shadow effects, and made its sculptors the founders of an original way of understanding plasticity and representation.

The friezes showing processions and religious festivals, mythological scenes, images of the gods and fantastic creatures, which together created a particular ritual atmosphere, different from that of the profane world, which deeply sensitized the visitor and prepared him psychologically for divine worship.

The first known example of this new practice is the sanctuary of Apollo, in Aetolia, which inaugurates this custom with great richness and variety, including mythological scenes and a profusion of figures of animals and fantastic beings such as mermaids, sphinxes and Gorgons.

By the mid-6th century BC figurative decoration on sacred buildings was common practice throughout Greece, with important examples in several places, such as the sanctuaries of Apollo in Aegina, of Hera in Olympia, of Artemis in Ephesus, and the Acropolis of Athens, where a gigantomachia of colossal dimensions was erected.

[47] In the late Archaic phase, particularly interesting are the friezes of the Treasury of Syphnos, in the sanctuary of Apollo at Delphi, which show a very advanced degree of compositional fluency and technical skill, which in many respects prefigure Classical art.

Their figures are of enormous refinement and elegance in finish and lines, and the variety of postures and solutions of movement, the detailing of anatomy, and the suggestion of diversified emotional expressions, despite the invariable Archaic smile, introduce notes of drama precursory to the developments of the psychological art of the Severe style and of Hellenistic sculpture.

[51] Similarly, the private possession of some prestigious image brought great social influence to its possessor, a cultural trait that was consistently exploited by the aristocracy to appropriate the charisma of divine power and create greater distance from the masses.

A very common form of ex-voto was the wooden plate painted with some religious or mythological scene, called pinax, but these have all disappeared owing to the fragility of the material, except for a handful found in Corinth.

Strabo states that in Archaic times images of worship of Athena were preferably represented in this position, but the relics we know of (about eighty examples) as a rule do not show enough distinctive features to identify the deity.

Their origin is obscure; the examples of bronze and terracotta statuettes from earlier times do not suggest a direct formal descent – rather it seems that their design derived from vase painting of the early 6th century BC.

The type flourished in Attica as a reflection of the aristocratic life of Athens, where several elite families had in their names components derived from hippos 'horse'; moreover the horse was an animal associated with Athena and Poseidon, the gods who in the founding myth of the city disputed its sovereignty, and so the depiction of knights took on special political and religious significance in the region.

Its absorption by the Greek colonies was a natural process, but it also inspired the formulation of the national Etruscan style of sculpture in the Italian peninsula, where it was adapted to the local context, abandoning stone as the material of choice in favor mainly of terracotta, even for architectural decoration.

[68] The Archaic style dissolved with the decline of the aristocracy and the rise of the democracy and bourgeoisie, and with the change in some basic concepts about the functions and properties of art mainly concerning mimesis, leading to a rapid introduction of an increasingly anatomically correct naturalism from the first decades of the 4th century BC, but its appeal did not completely disappear for sculptors.