Ard (plough)

In its simplest form it resembles a hoe, consisting of a draft-pole (either composite or a single piece) pierced with a nearly vertical, wooden, spiked head (or stock) which is dragged through the soil by draft animals and very rarely by people.

More sophisticated models have a composite pole, where the section attached to the head is called the draft-beam, and the share may be made of stone or iron.

It is restricted mainly to the Mediterranean (Spain, Tunisia, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon), Ethiopia, Iran, and eastern India and Sumatra.

The body ard dominates in Portugal, western Spain, the Balkans, India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Thailand, Japan, and most of Latin America.

Evidence of its use in prehistory is sometimes found at archaeological sites where the long, shallow scratches (ard marks) it makes can be seen cutting into the subsoil.

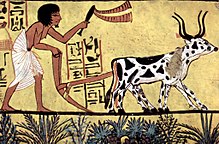

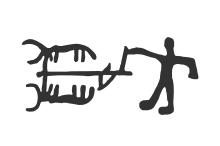

[8] All of these were bow ards, also depicted in the rock drawings of Bohuslän, Sweden, Copper Age stelae of Valcamonica (3000–2200 BC) and Fontanalba, France.

Today, a wooden brace between the draft-pole and upper stilt is a particular feature of body ards in Syria, central Iraq, Turkestan, and Gansu (China).

Today, the bow ard is confined to minority tribes and mountainous regions, but in earlier times was widely disseminated until ousted by the carruca turnplough beginning around AD 100.

In some parts of Europe with moist soils, the body ard's path was cleared by a ristle, a coulter-like implement used to reach greater depth.

A valuable reference book is Ard og Plov I Nordens Oldtid (with an extensive English summary)published by the Jutland Archeological Society of Aarhus University in 1951.

The book is illustrated including maps showing the archaeological sites in Northern Europe that have provided evidence of the use of the ard in prehistoric times.

1 - bow ard

2 - body ard

3 - sole ard [ 5 ]