Hannah Arendt

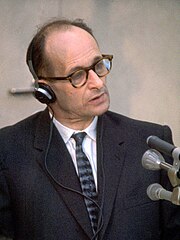

She is also remembered for the controversy surrounding the trial of Adolf Eichmann, for her attempt to explain how ordinary people become actors in totalitarian systems, which was considered by some an apologia, and for the phrase "the banality of evil."

"[37][d] In the last two years of the First World War, Hannah's mother organized social democratic discussion groups and became a follower of Rosa Luxemburg as socialist uprisings broke out across Germany.

In 1920, Martha Cohn married Martin Beerwald, an ironmonger and widower of four years, and they moved to his home, two blocks away, at Busoldstrasse 6,[41][42] providing Hannah with improved social and financial security.

Arendt's precocity continued, learning ancient Greek as a child,[46] writing poetry in her teenage years,[47] and starting both a Graecae (reading group for studying classical literature) and philosophy club at her school.

Reflecting on Rilke's opening lines, which she placed as an epigram at the beginning of their essay Wer, wenn ich schriee, hörte mich denn aus der Engel Ordnungen?

)Arendt and Stern begin by stating:[102] The paradoxical, ambiguous, and desperate situation from which standpoint the Duino Elegies may alone be understood has two characteristics: the absence of an echo and the knowledge of futility.

[142][143] On release, realizing the danger she was now in, Arendt and her mother fled Germany[31] following the established escape route over the Ore Mountains by night into Czechoslovakia and on to Prague and then by train to Geneva.

[31][158] In April 1939, following the devastating Kristallnacht pogrom of November 1938, Martha Beerwald realized her daughter would not return and made the decision to leave her husband and join Arendt in Paris.

[163] On 5 May 1940, in anticipation of the German invasion of France and the Low Countries that month, the military governor of Paris issued a proclamation ordering all "enemy aliens" between 17 and 55 who had come from Germany (predominantly Jews) to report separately for internment.

[173][174] Upon arriving in New York City on 22 May 1941 with very little, Hannah's family received assistance from the Zionist Organization of America and the local German immigrant population, including Paul Tillich and neighbors from Königsberg.

[175] She found the experience difficult but formulated her early appraisal of American life, Der Grundwiderspruch des Landes ist politische Freiheit bei gesellschaftlicher Knechtschaft (The fundamental contradiction of the country is political freedom coupled with social slavery).

[ad][176] On returning to New York, Arendt was anxious to resume writing and became active in the German-Jewish community, publishing her first article, "From the Dreyfus Affair to France Today" (in translation from her German) in July 1941.

In her capacity as executive secretary, she traveled to Europe, where she worked in Germany, Britain, and France (December 1949 to March 1950) to negotiate the return of archival material from German institutions, an experience she found frustrating, but provided regular field reports.

[217] Arendt wrote works on intellectual history as a political theorist, using events and actions to develop insights into contemporary totalitarian movements and the threat to human freedom presented by scientific abstraction and bourgeois morality.

Of the three, dilectio proximi or caritas[aj] is perceived as the most fundamental, to which the first two are oriented, which she treats as vita socialis (social life) – the second of the Great Commandments (or Golden Rule) "Thou shalt love thy neighbor as thyself" uniting and transcending the former.

[255] Arendt's Habilitationsschrift on Rahel Varnhagen was completed while she was living in exile in Paris in 1938, but not published till 1957, in the United Kingdom by East and West Library, part of the Leo Baeck Institute.

[267] The anthology of essays Men in Dark Times presents intellectual biographies of some creative and moral figures of the 20th century, such as Walter Benjamin, Karl Jaspers, Rosa Luxemburg, Hermann Broch, Pope John XXIII, and Isak Dinesen.

[274][275] After Arendt died in 1975, her essays and notes have continued to be collected, edited and published posthumously by friends and colleagues, mainly under the editorship of Jerome Kohn, including those that give some insight into the unfinished third part of The Life of the Mind.

[284][285][286] Arendt began writing poetry in her adolescence, but it was intensly personal and few knew of the existence of her poems till her archives at the Library of Congress were made accessible by McCarthy in 1988.

[288] Some further insight into her thinking is provided in the continuing posthumous publication of her correspondence with many of the important figures in her life, including Karl Jaspers (1992),[82] Mary McCarthy (1995),[195] Heinrich Blücher (1996),[289] Martin Heidegger (2004),[an][74] Alfred Kazin (2005),[290] Walter Benjamin (2006),[291] Gershom Scholem (2011)[292] and Günther Stern (2016).

"[301] She examined the question of whether evil is radical or simply a function of thoughtlessness, a tendency of ordinary people to obey orders and conform to mass opinion without a critical evaluation of the consequences of their actions.

[306] Arendt, who believed she could maintain her focus on moral principles in the face of outrage, became increasingly frustrated with Hausner, describing his parade of survivors as having "no apparent bearing on the case".

[322] Prior to Arendt's depiction of Eichmann, his popular image had been, as The New York Times put it "the most evil monster of humanity"[323] and as a representative of "an atrocious crime, unparalleled in history", "the extermination of European Jews".

Arendt herself had written in her book "This was outrageous, on the face of it, and also incomprehensible, since Kant's moral philosophy is so closely bound up with man's faculty of judgment, which rules out blind obedience.

"[328] Arendt's reply to Fest was subsequently corrupted to read Niemand hat das Recht zu gehorchen (No one has the right to obey), which has been widely reproduced, although it does encapsulate an aspect of her moral philosophy.

[330] A fascist bas-relief on the Palazzo degli Uffici Finanziari (1942), in the Piazza del Tribunale,[aw] Bolzano, Italy celebrating Mussolini, read Credere, Obbedire, Combattere (Believe, Obey, Combat).

The scene is based on Elisabeth Young-Bruehl's description in Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World (1982),[69] but reaches back to their childhoods, and Heidegger's role in encouraging the relationship between the two women.

[403][404]Kakutani and others believed that Arendt's words speak not just events of a previous century but apply equally to the contemporary cultural landscape[405] populated with fake news and lies.

Facts need testimony to be remembered and trustworthy witnesses to be established in order to find a secure dwelling place in the domain of human affairs[406]Arendt drew attention to the critical role that propaganda plays in gaslighting populations, Kakutani observes, citing the passage:[407][408] In an ever-changing, incomprehensible world the masses had reached the point where they would, at the same time, believe everything and nothing, think that everything was possible and that nothing was true .

[102] In Search of the Last Agora, an illustrated documentary film by Lebanese director Rayyan Dabbous about Hannah Arendt's 1958 work The Human Condition, was released in 2018 to mark the book's 50th anniversary.