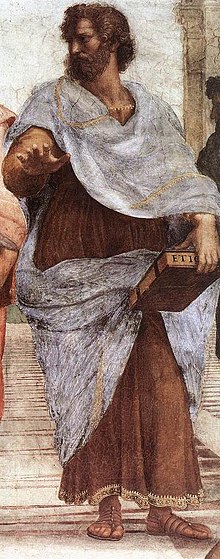

Aristotelianism

Aristotelianism (/ˌærɪstəˈtiːliənɪzəm/ ARR-i-stə-TEE-lee-ə-niz-əm) is a philosophical tradition inspired by the work of Aristotle, usually characterized by deductive logic and an analytic inductive method in the study of natural philosophy and metaphysics.

Aristotle and his school wrote tractates on physics, biology, metaphysics, logic, ethics, aesthetics, poetry, theatre, music, rhetoric, psychology, linguistics, economics, politics, and government.

Any school of thought that takes one of Aristotle's distinctive positions as its starting point can be considered "Aristotelian" in the widest sense.

This means that different Aristotelian theories (e.g. in ethics or in ontology) may not have much in common as far as their actual content is concerned besides their shared reference to Aristotle.

Moses Maimonides adopted Aristotelianism from the Islamic scholars and based his Guide for the Perplexed on it and that became the basis of Jewish scholastic philosophy.

Scholars such as Albertus Magnus and Thomas Aquinas interpreted and systematized Aristotle's works in accordance with Catholic theology.

After retreating under criticism from modern natural philosophers, the distinctively Aristotelian idea of teleology was transmitted through Wolff and Kant to Hegel, who applied it to history as a totality.

From this viewpoint, the early modern tradition of political republicanism, which views the res publica, public sphere or state as constituted by its citizens' virtuous activity, can appear thoroughly Aristotelian.

MacIntyre revises Aristotelianism with the argument that the highest temporal goods, which are internal to human beings, are actualized through participation in social practices.

[8] In the 9th century, Persian astrologer Albumasarl's Introductorium in Astronomiam was one of the most important sources for the recovery of Aristotle for medieval European scholars.

[9] The philosopher Al-Farabi (872–950) had great influence on science and philosophy for several centuries, and in his time was widely thought second only to Aristotle in knowledge (alluded to by his title of "the Second Teacher").

[11] The school of thought he founded became known as Avicennism, which was built on ingredients and conceptual building blocks that are largely Aristotelian and Neoplatonist.

Although some knowledge of Aristotle seems to have lingered on in the ecclesiastical centres of western Europe after the fall of the Roman empire, by the ninth century, nearly all that was known of Aristotle consisted of Boethius's commentaries on the Organon, and a few abridgments made by Latin authors of the declining empire, Isidore of Seville and Martianus Capella.

[22] He digested, interpreted and systematized the whole of Aristotle's works, gleaned from the Latin translations and notes of the Arabian commentators, in accordance with Church doctrine.

Albertus famously wrote: "Scias quod non perficitur homo in philosophia nisi ex scientia duarum philosophiarum: Aristotelis et Platonis."

[24] Thomas was emphatically Aristotelian, he adopted Aristotle's analysis of physical objects, his view of place, time and motion, his proof of the prime mover, his cosmology, his account of sense perception and intellectual knowledge, and even parts of his moral philosophy.

[24] The philosophical school that arose as a legacy of the work of Thomas Aquinas was known as Thomism, and was especially influential among the Dominicans, and later, the Jesuits.

[24] Using Albert's and Thomas's commentaries, as well as Marsilius of Padua's Defensor pacis, 14th-century scholar Nicole Oresme translated Aristotle's moral works into French and wrote extensively comments on them.

After retreating under criticism from modern natural philosophers, the distinctively Aristotelian idea of teleology was transmitted through Wolff and Kant to Hegel, who applied it to history as a totality.

[citation needed] From this viewpoint, the early modern tradition of political republicanism, which views the res publica, public sphere or state as constituted by its citizens' virtuous activity, can appear thoroughly Aristotelian.

MacIntyre revises Aristotelianism with the argument that the highest temporal goods, which are internal to human beings, are actualized through participation in social practices.

This thesis does not deny our common-sense intuition that the distinct objects we encounter in our everyday affairs like cars or other people exist.

This immanence can be conceived in terms of the theory of hylomorphism by seeing objects as composed of a universal form and the matter shaped by it.