John Wallis

[citation needed] Throughout this time, Wallis had been close to the Parliamentarian party, perhaps as a result of his exposure to Holbeach at Felsted School.

The quality of cryptography at that time was mixed; despite the individual successes of mathematicians such as François Viète, the principles underlying cipher design and analysis were very poorly understood.

Most ciphers were ad hoc methods relying on a secret algorithm, as opposed to systems based on a variable key.

Wallis realised that the latter were far more secure – even describing them as "unbreakable", though he was not confident enough in this assertion to encourage revealing cryptographic algorithms.

He was also concerned about the use of ciphers by foreign powers, refusing, for example, Gottfried Leibniz's request of 1697 to teach Hanoverian students about cryptography.

[11] Returning to London – he had been made chaplain at St Gabriel Fenchurch in 1643 – Wallis joined the group of scientists that was later to evolve into the Royal Society.

[12] Wallis joined the moderate Presbyterians in signing the remonstrance against the execution of Charles I, by which he incurred the lasting hostility of the Independents.

In spite of their opposition he was appointed in 1649 to the Savilian Chair of Geometry at Oxford University, where he lived until his death on 8 November [O.S.

[citation needed] Besides his mathematical works he wrote on theology, logic, English grammar and philosophy, and he was involved in devising a system for teaching a deaf boy to speak at Littlecote House.

[13] William Holder had earlier taught a deaf man, Alexander Popham, to speak "plainly and distinctly, and with a good and graceful tone".

[15] The Parliamentary visitation of Oxford, that began in 1647, removed many senior academics from their positions, including in November 1648, the Savilian Professors of Geometry and Astronomy.

Wallis seems to have been chosen largely on political grounds (as perhaps had been his Royalist predecessor Peter Turner, who despite his appointment to two professorships never published any mathematical works); while Wallis was perhaps the nation's leading cryptographer and was part of an informal group of scientists that would later become the Royal Society, he had no particular reputation as a mathematician.

Nonetheless, Wallis' appointment proved richly justified by his subsequent work during the 54 years he served as Savilian Professor.

He began, after a short tract on conic sections, by developing the standard notation for powers, extending them from positive integers to rational numbers: Leaving the numerous algebraic applications of this discovery, he next proceeded to find, by integration, the area enclosed between the curve y = xm, x-axis, and any ordinate x = h, and he proved that the ratio of this area to that of the parallelogram on the same base and of the same height is 1/(m + 1), extending Cavalieri's quadrature formula.

He apparently assumed that the same result would be true also for the curve y = axm, where a is any constant, and m any number positive or negative, but he discussed only the case of the parabola in which m = 2 and the hyperbola in which m = −1.

[clarification needed] This, by an elaborate method that is not described here in detail, leads to a value for the interpolated term which is equivalent to taking (which is now known as the Wallis product).

In this he incidentally explained how the principles laid down in his Arithmetica Infinitorum could be used for the rectification of algebraic curves and gave a solution of the problem to rectify (i.e., find the length of) the semicubical parabola x3 = ay2, which had been discovered in 1657 by his pupil William Neile.

He supposes the curve to be referred to rectangular axes; if this is so, and if (x, y) are the coordinates of any point on it, and n is the length of the normal,[clarification needed] and if another point whose coordinates are (x, η) is taken such that η : h = n : y, where h is a constant; then, if ds is the element of the length of the required curve, we have by similar triangles ds : dx = n : y.

The solutions given by Neile and Wallis are somewhat similar to that given by van Heuraët, though no general rule is enunciated, and the analysis is clumsy.

In 1685 Wallis published Algebra, preceded by a historical account of the development of the subject, which contains a great deal of valuable information.

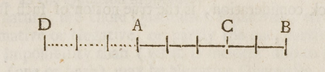

This perhaps will be made clearer by noting that the relation between the space described in any time by a particle moving with a uniform velocity is denoted by Wallis by the formula where s is the number representing the ratio of the space described to the unit of length; while the previous writers would have denoted the same relation by stating what is equivalent to the proposition Wallis has been credited as the originator of the number line "for negative quantities"[18] and "for operational purposes.

Yards Backward.It has been noted that, in an earlier work, Wallis came to the conclusion that the ratio of a positive number to a negative one is greater than infinity.

However, Thabit Ibn Qurra (AD 901), an Arab mathematician, had produced a generalisation of the Pythagorean theorem applicable to all triangles six centuries earlier.

The book was based on his father's thoughts and presented one of the earliest arguments for a non-Euclidean hypothesis equivalent to the parallel postulate.

It was a feat that was considered remarkable, and Henry Oldenburg, the Secretary of the Royal Society, sent a colleague to investigate how Wallis did it.

[4] While employed as lady Vere's chaplain in 1642 Wallis was given an enciphered letter about the fall of Chicester which he managed to decipher within two hours.

The king took a personal interest in Wallis' work and well-being as witnessed by a letter he sent to Dutch Grand pensionary Anthonie Heinsius in 1689.

[29] In these early days of the Williamite reign directly obtaining foreign intercepted letters was a problem for the English, as they did not have the resources of foreign Black Chambers as yet, but allies like the Elector of Brandenburg without their own Black Chambers occasionally made gifts of such intercepted correspondence, like the letter of king Louis XIV of France to king John III Sobieski of Poland that king William in 1689 used to cause a crisis in French-Polish diplomatic relations.

[37] Wallis tried to teach his own son John, and his grandson by his daughter Anne, William Blencowe the tricks of the trade.

With William he was so successful that he could persuade the government to allow the grandson to get the survivorship of the annual pension of £100 Wallis had received in compensation for his cryptographic work.