Arius

Arian theology and its doctrine regarding the nature of the Godhead showed a belief in radical subordinationism,[3] a view notably disputed by 4th century figures such as Athanasius of Alexandria.

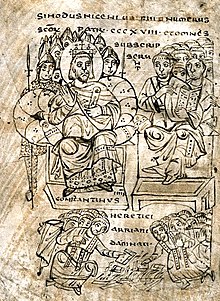

[4] Constantine the Great's formal decriminalization of Christianity into the Roman Empire entailed the convention of ecumenical councils to remove theological divisions between opposing sects within the Church.

Arius's theology was a prominent topic at the First Council of Nicaea, where Arianism was condemned in favor of Homoousian conceptions of God and Jesus.

"[5] Nevertheless, despite concerted opposition, Arian churches persisted for centuries throughout Europe (especially in various Germanic kingdoms), the Middle East, and North Africa.

"[6] Richard Hanson writes that Arius' specific espousal of subordinationist theology brought "into unavoidable prominence a doctrinal crisis which had gradually been gathering[...] He was the spark that started the explosion.

"[7] The association between Arius and the theology titled after him has been argued to be a creation "based on the polemic of Nicene writers" such as Athanasius of Alexandria, a Homoousian.

Although his character has been severely assailed by his opponents, Arius appears to have been a man of personal ascetic achievement, pure morals, and decided convictions.

"He was very tall in stature, with downcast countenance ... always garbed in a short cloak and sleeveless tunic; he spoke gently, and people found him persuasive and flattering.

However:"A great deal of recent work seeking to understand Arian spirituality has, not surprisingly, helped to demolish the notion of Arius and his supporters as deliberate radicals, attacking a time-honoured tradition.

The Arian Controversy began only 5 years later in 318 when Arius, who was in charge of one of the churches in Alexandria, publicly criticized his bishop Alexander for "carelessness in blurring the distinction of nature between the Father and the Son by his emphasis on eternal generation".

Socrates of Constantinople believed that Arius was influenced in his thinking by the teachings of Lucian of Antioch, a celebrated Christian teacher and martyr.

"[35] "We cannot accordingly describe Eusebius (of Caesarea) as a formal Arian in the sense that he knew and accepted the full logic of Arius, or of Asterius' position.

"[42]However, because Origen's theological speculations were often proffered to stimulate further inquiry rather than to put an end to any given dispute, both Arius and his opponents were able to invoke the authority of this revered (at the time) theologian during their debate.

Emperor Constantine had taken a personal interest in several ecumenical issues, including the Donatist controversy in 316, and he wanted to bring an end to the Christological dispute.

Hosius was armed with an open letter from the Emperor: "Wherefore let each one of you, showing consideration for the other, listen to the impartial exhortation of your fellow-servant."

For going out of the imperial palace, attended by a crowd of Eusebian partisans like guards, he paraded proudly through the midst of the city, attracting the notice of all the people.

Soon after a faintness came over him, and together with the evacuations his bowels protruded, followed by a copious hemorrhage, and the descent of the smaller intestines: moreover portions of his spleen and liver were brought off in the effusion of blood, so that he almost immediately died.

The scene of this catastrophe still is shown at Constantinople, as I have said, behind the shambles in the colonnade: and by persons going by pointing the finger at the place, there is a perpetual remembrance preserved of this extraordinary kind of death.

[71]Following the abortive effort by Julian the Apostate to restore paganism in the empire, the emperor Valens—himself an Arian—renewed the persecution of Nicene bishops.

However, Valens's successor Theodosius I ended Arianism once and for all among the elites of the Eastern Empire through a combination of imperial decree, persecution, and the calling of the First Council of Constantinople in 381 that condemned Arius anew while reaffirming and expanding the Nicene Creed.

Arians continued to exist in North Africa, Spain and portions of Italy until they were finally suppressed during the sixth and seventh centuries.

[73] In the 12th century, the Benedictine abbot Peter the Venerable described the Islamic prophet Muhammad as "the successor of Arius and the precursor to the Antichrist".

Contemporary Unitarian Universalist Christians often may be either Arian or Socinian in their Christology, seeing Jesus as a distinctive moral figure but not equal or eternal with God the Father; or they may follow Origen's logic of Universal Salvation, and thus potentially affirm the Trinity, but assert that all are already saved.

The Synod of Antioch, which condemned Paul of Samosata, had expressed its disapproval of the word homoousios in one sense, while Bishop Alexander undertook its defense in another.

Although the controversy seemed to be leaning toward the opinions later championed by Arius, no firm decision had been made on the subject; in an atmosphere so intellectual as that of Alexandria, the debate seemed bound to resurface—and even intensify—at some point in the future.

Arius's Thalia (literally, 'festivity', 'banquet'), a popularized work combining prose and verse and summarizing his views on the Logos,[85] survives in quoted fragmentary form.

[89] But although these quotations seem reasonably accurate, their proper context is lost, so their place in Arius's larger system of thought is impossible to reconstruct.

"[92] The Opitz edition with the West translation is as follows: Αὐτὸς γοῦν ὁ θεὸς καθό ἐστιν ἄρρητος ἅπασιν ὑπάρχει.

ἀρχὴν τὸν υἰὸν ἔθηκε τῶν γενητῶν ὁ ἄναρχος καὶ ἤνεγκεν εἰς υἱὸν ἑαυτῷ τόνδε τεκνοποιήσας, ἴδιον οὐδὲν ἔχει τοῦ θεοῦ καθ᾽¦ ὑπόστασιν ἰδιότητος, οὐδὲ γάρ ἐστιν ἴσος, ἀλλ' οὐδὲ ὁμοούσιος αὐτῷ.

λοιπὸν ὁ υἰὸς οὐκ ὢν (ὐπῆρξε δὲ θελήσει πατρῴᾳ) μονογενὴς θεός ἐστι καὶ ἑκατέρων ἀλλότριος οὗτος.