History of the University of Texas at Arlington (1895–1917)

The school was molded by Carlisle's educational philosophy, which balanced intellectualism with military training to instill discipline in students and prepare them for enrollment in elite colleges.

Like its predecessors, the school attempted to balance intellectualism with military exercises, instill discipline into its students, and prepare them for attending a university or a career in business.

In January 1917, Arlington leaders met to organize an effort to convince the Texas Legislature to grant the community a junior college in place of a military academy.

[7][12] That year, the Arlington College Corporation was established to run the school, with newly appointed president W. W. Franklin of Dallas.

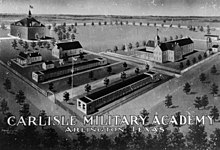

[25] On opening day in September 1902, 48 students were enrolled in Carlisle Military Academy, and by the end of the academic year in May 1903, that number had grown to 71.

[29] In September 1905, due in part to the school's struggles to handle increases in enrollment, it stopped accepting female students and reduced its advertising.

[31] Carlisle required parents to give the school "complete authority" over their children while they attended, while also prohibiting tobacco and advertising Arlington as a "Christian community" without saloons.

[33] By 1906, the school had expanded to four blocks in size, and by 1911 it had constructed an athletics track, additional barracks, a gymnasium, and an indoor swimming pool.

In March 1907, United States Army lieutenant Harry King visited the school and became convinced that Carlisle Military Academy was one of the best institutions of its kind in the country.

[29] In summer 1907, after inspecting the school, the United States Department of War assigned an active-duty officer, lieutenant Kelton L. Pepper, to the academy.

[38] In an effort to raise revenue, Carlisle again allowed female students to enroll in 1908 and converted the academy's real estate (four city blocks in all) to capital stock.

[24] During receivership, General R. H. Beckham, who was appointed the receiver by the county's district court, settled suits with the school's creditors after Carlisle was unable to meet his obligations to them.

Beckham also managed the school's affairs, ensured all its buildings had fire insurance, compiled lists of all its property and liabilities, and continued to employ teachers and staff while, so long as possible, paying them with cash on hand.

[39] After operating for two more years, in August 1913 Carlisle Military Academy was ordered by the court to sell its property to satisfy its obligations with the bank and its lienholders.

When bank officer Thomas Spruance purchased its land for $15,610 in a public sale, the school was ordered to pay off as much of the deficit as possible by selling its other property.

[4] Suffering from inefficient management, the school was hurt by its increasing debts, declining enrollments, and overly optimistic plans for expansion.

[22][43] While he was ultimately unable to maintain the school in Arlington, Carlisle did significantly improve its buildings, curriculum, and reputation, which resulted in high hopes for its successor institutions.

[43] Carlisle Military Academy had been well regarded in North Texas,[3] and The Whitewright Sun described it as noted for its "development of boys into strong men".

He served as president of Northwest State Teachers College in Maryville, Missouri, from 1909 to 1913, where he earned a reputation as a capable administrator.

After arriving in Texas, Taylor reached an agreement with Carlisle Military Academy's property owners in which he promised to improve and insure the campus's buildings, organize an advertising campaign, and employ a competent staff in exchange for being allowed to keep any profits generated and having the opportunity to purchase the school and its land outright for $18,000.

[45] Conceiving itself as a place for "gentlemen's sons" and not a reformatory for "vicious boys", again similar in this regard to its predecessor, Arlington Training School emphasized developing students to be hardworking, polite, and respectful.

[50] To graduate, a student had to complete seventeen "units of work" at the secondary level, which met the University of Texas at Austin's entrance requirements.

[50][51] At the secondary level, the school offered a comprehensive curriculum with courses in mathematics, history, the sciences, English, and foreign languages, as well as vocational subjects such as agriculture, bookkeeping, and business law.

Encouraged by this support, Taylor made plans to hire new faculty members and improve the school's buildings and grounds for the next year.

The Arlington Journal reported that this failure was a result of the "difference of opinion regarding the value of the property" between Taylor and the advisory board, which was only the first disagreement between the two.

Taylor, in a letter to the local newspaper, revealed his further plans to improve the campus's buildings and even transform the school into a junior college that would offer courses in agriculture, home economics, and manual training, as well as host an experimental farm and demonstration service.

The plan was supported by the director of the Texas A&M College extension department, Clarence Owsley, and the Tarrant County farm demonstrator, G. W. Eudaly.

By the time of the verdict, however, Taylor had already left Arlington to work as an extension agent at Texas Woman's College in Denton.

[55] Like its predecessors, the school attempted to balance intellectualism with military exercises, instill discipline into its students, and prepare them for attending a university or a career in business.

Instead of trying to save it, in January 1917 Arlington leaders met to organize an effort to convince the Texas Legislature to grant the community a junior college in place of a military academy.