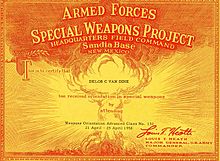

Armed Forces Special Weapons Project

The short life of their lead-acid batteries and modulated neutron initiators, and the heat generated by the fissile cores, precluded storing them assembled.

The AFSWP gradually shifted its emphasis away from training assembly teams, and became more involved in stockpile management and providing administrative, technical, and logistical support.

[2] After the war ended, the Manhattan Project supported the nuclear weapons testing at Bikini Atoll as part of Operation Crossroads in 1946.

One of Secretary of the Navy James Forrestal's aides, Lewis Strauss, proposed this series of tests to refute "loose talk to the effect that the fleet is obsolete in the face of this new weapon".

[3] The nuclear weapons were handmade devices, and a great deal of work remained to improve their ease of assembly, safety, reliability and storage before they were ready for production.

The military side of the Manhattan Project had relied heavily on reservists, as the policy of the Corps of Engineers was to assign regular officers to field commands.

To replace them, Groves asked for fifty West Point graduates from the top ten percent of their classes to man bomb-assembly teams at Sandia Base, where the assembly staff and facilities had been moved from Los Alamos and Wendover Field in September and October 1945.

[8] Groves hoped a new, permanent agency would be created to take over the responsibilities of the wartime Manhattan Project in 1945, but passage of the Atomic Energy Act of 1946 through Congress took much longer than expected, and involved considerable debate about the proper role of the military with respect to the development, production and control of nuclear weapons.

In February 1947, Eisenhower and Chief of Naval Operations Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz appointed Groves as head of the AFSWP, with Parsons as his deputy.

[20] Groves initially established the headquarters of the AFSWP in the old offices of the Manhattan Project on the fifth floor of the New War Department Building in Washington, DC, but on 15 April 1947 it moved to the Pentagon.

[21] As AFSWP headquarters expanded, it filled up its original accommodation, and began using office space in other parts of the building, which was not satisfactory from a security point of view.

For training purposes, Company B was initially divided into command, electrical, mechanical and nuclear groups, but the intention was to create three integrated 36-man bomb assembly teams.

[28][29] During the late 1940s the Air Force gradually became the major user of nuclear weapons, and by the end of 1949 it had twelve assembly units and another three in training.

[30] When the Air Force moved to make the temporary arrangement permanent in September 1948, the Army and Navy objected, and the Military Liaison Committee directed that the AFSWP should remain a tri-service organization answerable to the three service chiefs.

[31] Groves and the wartime director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, Robert Oppenheimer, had begun the move of ordnance functions to Sandia in late 1945.

Meeting with Truman in April 1947, Lilienthal informed him that not only were there no assembled weapons, there were only a few sets of components and no fully trained bomb-assembly teams.

The cores had to be stored separately from the high-explosive blocks that would surround them in the bomb because they generated enough heat to melt the plastic explosive over time.

[42] Over the following ten days, they assembled bombs and flew training missions with them, including a live drop at the Naval Ordnance Test Station at Inyokern, California.

[44] In another exercise in November 1948, the 471st Special Weapons Unit flew to Norfolk, Virginia, and practiced bomb assembly on board the Midway-class aircraft carriers.

[46] He did this so well that Strauss, now an AEC commissioner, became disturbed at the number of AFSWP personnel who were participating, and feared that the Soviet Union might launch a sneak attack on Enewetak to wipe out the nation's ability to assemble nuclear weapons.

[48] The new Mark 4 nuclear bomb the AEC began delivering in 1949 was a production design that was much easier to assemble and maintain, and enabled a bomb-assembly team to be reduced to just 46 men.

[55] For his part, Groves suspected the AEC was not keeping bomb components in the condition in which the military wanted to receive them, and Operation Ajax only confirmed his suspicions.

[57] On 11 March, Truman summoned Lilienthal, Nichols and Secretary of the Army Kenneth C. Royall to his office, and told them he expected the AFSWP and the AEC to cooperate.

[59] Norris Bradbury, who had replaced Oppenheimer as the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory in December 1945, argued that rapid transfer could be accomplished by improved procedures and that the other difficulties could best be resolved by further development, mostly from the scientists.

"[61] With the outbreak of the Korean War in 1950, air transport resources were put under great strain, and it was decided to reduce the requirement for it by pre-positioning non-nuclear components at locations in Europe and the Pacific.

[63] In April 1951, the AEC released nine Mark 4 weapons to the Air Force in case the Soviet Union intervened in the war in Korea.

[66] In the light of this, a new AEC-AFSWP agreement on "Responsibilities of Stockpile Operations" was drawn up in August 1951, but in December, the Joint Chiefs of Staff began a new push for weapons to be permanently assigned to the armed forces, so as to ensure a greater degree of flexibility and a higher state of readiness.

It began moving away from training assembly teams, which were increasingly not required, as its primary mission, and became more involved in the management of the rapidly growing nuclear stockpile, and providing technical advice and logistical support.

[73] On 16 October 1953, the Secretary of Defense charged the AFSWP with responsibility for "a centralized system of reporting and accounting to ensure that the current status and location" of all nuclear weapons "will be known at all times".

The Army and Air Force had rival programs, PGM-19 Jupiter and PGM-17 Thor respectively, and the additional cost to the taxpayers of developing two systems instead of one was estimated at $500 million.

- AN 219 contact fuze (four)

- Archie radar antenna

- Plate with batteries (to detonate charge surrounding nuclear components)

- X-Unit, a firing set placed near the charge

- Hinge fixing the two ellipsoidal parts of the bomb

- Physics package (see details below)

- Plate with instruments (radars, baroswitches and timers)

- Barotube collector

- California Parachute tail assembly (0.20-inch (5.1 mm) aluminium sheet)