Armored cruiser

For many decades, naval technology had not advanced far enough for designers to produce a cruiser that combined an armored belt with the long-range and high speed required to fulfill its mission.

Although they were now considered second-rate ships, armored cruisers were still widely used in World War I due to their speed and range, and being able to outgun all but battlecruisers and battleships (both pre-dreadnought and dreadnought types).

The concern within higher naval circles was that without ships that could fulfill these requirements and incorporate new technology, their fleet would become obsolete and ineffective should a war at sea arise.

Both these protective schemes used wood as an important component, which made them extremely heavy and limited speed, the key factor in a cruiser's ability to perform its duties satisfactorily.

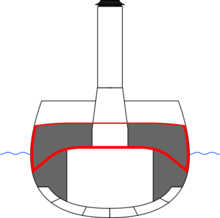

Past this belt, the designers placed a 3-inch (76 mm) armored deck, situated deepest in the ships, to guard magazines and machinery against plunging fire.

The Jeune Ecole school of thought, which proposed a navy composed of fast cruisers for commerce raiding and torpedo-boats for coast defense, was particularly influential in France.

They combined long range, high speed and an armament approaching that of battleship with enough armor to protect them against quick-firing guns, considered the most important weapons afloat at the time.

They saved further weight by not requiring a heavy timber backing, as previous armor plating had, to soften and spread the force of the impact from oncoming shells; 2.5 inches (64 mm) of teak to give a fair surface upon which to attach them was all that was needed.

Steel bulkheads added strength to the hull, while armor as thick as the belt covered the guns and heavier protection surrounded the conning tower.

[18][full citation needed] The ideas presented by Mahan prompted French Admiral Ernest François Fournier to write his book La flotte necessaire in 1896.

Fournier argued that a fleet of technologically advanced armored cruisers and torpedo craft would be powerful and flexible enough to engage in a wide range of activity and overwhelm potential enemies.

French naval and government circles embraced this ideal mutually and even advocates of battleships over cruisers admitted the latter's potential usefulness in scouting and commercial warfare.

Jeanne d'Arc, laid down in 1896, displaced 11,000 tons, carried a mixed armament of 194-millimetre (7.6 in) and 138-millimetre (5.4 in) guns, and had a 150-millimetre (5.9 in) belt of Harvey armor over her machinery spaces.

[20] Japan, which now received British technical assistance in naval matters and purchased larger vessels from France and Britain, began an armored cruiser program of its own.

The hull protection of both ships was superior to their main rival, the British Blake class, which were the largest cruisers at the time but had no side armor.

Moreover, New York's builder diverged from the Navy blueprint by rearranging her boilers during construction; this allowed the installation of additional transverse and longitudinal bulkheads, which increased her underwater protection.

"[26] Shortly after the war ended, the Navy laid down six Pennsylvania-class armored cruisers to take advantage of lessons learned and better control the large sea areas the nation had just gained.

Much larger than their predecessors (displacing 14,500 tons as compared to 8150 for New York), the Pennsylvanias "were closer to light battleships than to cruisers," according to naval historian William Friedman.

The 1904 edition of the Encyclopedia Americana quotes an otherwise unidentified Captain Walker, USN, in describing the role of the armored cruiser as "that of a vessel possessing in a high degree offensive and defensive qualities, with the capacity of delivering her attack at points far distant from her base in the least space of time."

[32] Danish Navy Commander William Hovgaard, who would later become president of New York Shipbuilding and serve on the U.S. Navy's Battleship Design Advisory Board, a group which would help plan the Iowa-class fast battleships in the 1930s, said, "The fighting capacity of the armored cruiser has reached a point which renders its participation in future fleet actions almost a certainty" and called for a "battleship-cruiser" which would possess the speed of a cruiser and the firepower of a capital ship[33] Other naval authorities remained skeptical.

The Tsukubas were intended to take the place of aging battleships and thus showed Japan's intention of continuing to use armored cruisers in fleet engagements.

[39] One week after the final decision to construct Blücher, the German naval attache learned they would carry eight 30.5 cm (12.0 in) guns, the same type mounted on battleships.

Because they carried the heavy guns normally ascribed to battleships, they could also theoretically hold their place in a battle line more readily than armored cruisers and serve as the "battleship-cruiser" for which Hovgaard had argued after Tsushima.

[43]Later in the same address is this: "Every argument used against [armored cruisers] holds true for battle-cruisers of the Invincible type, except that the latter, if wounded, would be fit to lie in the line, owing to her great armament.

Their armor and firepower was sufficient to defeat other cruiser types and armed merchant vessels, while their speed and range made them particularly useful for extended operations out in the high seas.

This victory seemed to validate Lord "Jacky" Fisher's justification in building battlecruisers—to track down and destroy armored cruisers with vessels possessing superior speed and firepower.

The Harvey and Krupp Cemented armor that had looked to offer protection failed when hit with soft capped AP shells of large enough size.

Only a small number of armored cruisers survived these limitations, though a handful saw action in World War II in marginal roles; The Hellenic Navy's Georgios Averof, constructed in 1909, served with the British Navy as a convoy escort in the Indian Ocean after the fall of Greece, while a number of Japanese armored cruisers were still active as minelayers or training vessels.

The Swedish Navy's HSwMS Fylgia underwent an extensive modernization from 1939 to 1940 and conducted neutrality patrols in the Baltic Sea during World War II.

The only armored cruiser still considered to be in existence, as well as in active duty, is the aforementioned Georgios Averof, preserved as a museum in Palaio Faliro, Greece.