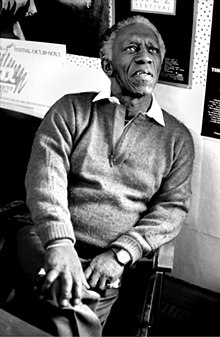

Art Blakey

The group was formed as a collective of contemporaries, but over the years the band became known as an incubator for young talent, including Freddie Hubbard, Wayne Shorter, Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Kenny Dorham, Hank Mobley, Donald Byrd, Jackie McLean, Johnny Griffin, Curtis Fuller, Chuck Mangione, Chick Corea, Keith Jarrett, Cedar Walton, Woody Shaw, Terence Blanchard, and Wynton Marsalis.

His biological father was Bertram Thomas Blakey, originally of Ozark, Alabama, whose family migrated northward to Pittsburgh sometime between 1900 and 1910.

[6]: 8–10 [10] From 1939 to 1944, Blakey played with fellow Pittsburgh native Mary Lou Williams and toured with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra.

)[13][15][16] While playing in Henderson's band, Blakey was subjected to an unprovoked attack by a white Georgia police officer which necessitated a steel plate being inserted into his head.

The octet included Kenny Dorham, Sahib Shihab, Musa Kaleem, and Walter Bishop, Jr.[24] Around the same time (1947[2][10] or 1949[6]: 20 [8]) he led a big band called Seventeen Messengers.

[6]: 20 The use of the Messengers tag finally stuck with the group co-led at first by both Blakey and pianist Horace Silver, though the name was not used on the earliest of their recordings.

[30][31] Golson, as musical director, wrote several jazz standards which began as part of the band book, such as "I Remember Clifford", "Along Came Betty", and "Blues March", and were frequently revived by later editions of the group.

[8] From 1959 to 1961, the group featured Wayne Shorter on tenor saxophone, Lee Morgan on trumpet, pianist Bobby Timmons and Jymie Merritt on bass.

From 1961 to 1964, the band was a sextet that added trombonist Curtis Fuller and replaced Morgan, Timmons, and Merritt with Freddie Hubbard, Cedar Walton, and Reggie Workman, respectively.

The group evolved into a proving ground for young jazz talent, and recorded albums such as Buhaina's Delight, Caravan, and Free For All.

While veterans occasionally reappeared in the group, by and large, each iteration of the Messengers included a lineup of new young players.

[7][10][14][32] Many Messenger alumni went on to become jazz stars in their own right, such as: Lee Morgan, Benny Golson, Wayne Shorter, Freddie Hubbard, Bobby Timmons, Curtis Fuller, Chuck Mangione, Keith Jarrett, Joanne Brackeen, Woody Shaw, Wynton Marsalis, Branford Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Donald Harrison and Mulgrew Miller.

He had a policy of encouraging young musicians: as he remarked on-mic during the live session which resulted in the A Night at Birdland albums in 1954: "I'm gonna stay with the youngsters.

Javon Jackson, who played in Blakey's final lineup, claimed that he exaggerated the extent of his hearing loss.

In the words of drummer Cindy Blackman shortly after Blakey's death, "When jazz was in danger of dying out [during the 1970s], there was still a scene.

[1] Japanese video game music composer Yasunori Mitsuda, who composed the Chrono and Xeno video game soundtracks, cited Art Blakey as the jazz musician who had the deepest influence on him, due to his father frequently playing his music.

He married his first wife, Clarice Stewart, while yet a teen, then Diana Bates (1956), Atsuko Nakamura (1968), and Anne Arnold (1983[42]).

[1] He had 10 children from these relationships — Gwendolyn, Evelyn, Jackie, Kadijah, Sakeena, Akira, Art Jr., Takashi, Kenji and Gamal.

[44][45][46] Blakey traveled for a year in West Africa in 1948 to explore the culture and religion of Islam, which he later adopted alongside changing his name; his conversion took place in the late 1940s at a time when other African Americans were being influenced by the Ahmadi missionary Kahili Ahmed Nasir, according to the Encyclopedia of Muslim-American History, and at one time in that period, Blakey led a turbaned, Qur'an-reading jazz band called the 17 Messengers (perhaps all Muslim, reflecting notions of the Prophet's and music's roles as conduits of the divine message).

[1] A friend recollects that when "Art took up the religion [...] he did so on his own terms", saying that "Muslim imams would come over to his place, and they would pray and talk, then a few hours later [we] would go [...] to a restaurant [...and] have a drink and order some ribs", and suggests that reasons for the name change included the pragmatic: that "like many other black jazz musicians who adopted Muslim names", musicians did so to allow themselves to "check into hotels and enter 'white only places' under the assumption they were not African-American".

[42][47] Other specific recollections have Blakey forswearing serious drink while playing (after being disciplined by drummer Sid Catlett early in his career for drinking while performing), and suggest that the influence of "clean-living cat" Wynton Marsalis led to a period where he was less affected by drugs during performances.

He was survived by nine children: Gwendolyn, Evelyn, Jackie, Sakeena, Kadijah, Akira, Takashi, Gamal, and Kenji.

[11] At his funeral at the Abyssinian Baptist Church on October 22, 1990, a tribute group assembled of past Jazz Messengers including Brian Lynch, Javon Jackson, Geoffrey Keezer, Wynton Marsalis, Terence Blanchard, Valery Ponomarev, Benny Golson, Donald Harrison, Essiet Okon Essiet, and drummer Kenny Washington performed several of the band's most celebrated tunes, such as Golson's "Along Came Betty", Bobby Timmons' "Moanin'", and Wayne Shorter's "One by One".

Jackson, a member of Blakey's last Jazz Messengers group, recalled how his experiences with the drummer changed his life, saying that "He taught me how to be a man.

Musicians Jackie McLean, Ray Bryant, Dizzy Gillespie, and Max Roach also paid tribute to Blakey at his funeral.