Art and World War II

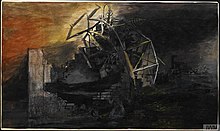

For instance, Paul Nash's Battle of Britain (1941) represents a scene of aerial combat between British and German fighters over the English channel.

On the other hand, André Fougeron's Street of Paris (1943) focuses on the impact of war and occupation by armed forces on civilians.

In totalitarian regimes (especially in Hitler’s Germany), the control of art and other cultural expressions was an integral part of the establishment of power.

In Europe, other totalitarian regimes adopted a similar stance on art and encouraged or imposed an official aesthetic, which was a form of Realism.

[citation needed] It was clear in Stalin’s Soviet Union, where diversity in the arts was proscribed and “Socialist Realism” was instituted as the official style.

Cultural actors who were labelled “un-German” by the regime were persecuted: they were fired from their teaching positions, artworks were removed from museums, books were burnt.

The works were placed in unflattering ways, with derogatory comments and slogans painted around them (“Nature as seen by sick minds”, “Deliberate sabotage of national defense”...).

Resistance was dangerous and unlikely to escape fierce punishment and while collaboration offered an easier path principled objection to it was a strong deterrent to many if not most.

Some sought collaboration with others in exile, forming groups to exhibit, such as the Free German League of Culture founded in 1938 in London.

On the contrary, someone like Oskar Kokoschka, who had until then rejected the idea that art should be useful and serve a cause, got involved in these groups when he emigrated to London in 1938.

[citation needed] Inside the camps, some of the inmates were artists, musicians, and other intelligentsia, and they rebuilt as much cultural life as they could within the constraints of their imprisonment: the giving of lectures and concerts and the creation of artworks from materials like charcoal from burnt twigs, dyes from plants and the use of lino and newspaper.

They risked deportation, forced labour and extermination in the case of Jewish artists, both in occupied France and in the Vichy Republic.

[citation needed] In the US, citizens of Japanese extraction also faced internment in very poor living conditions and with little sympathy for their plight throughout the period of hostilities and beyond.

The works they produced during the period were characterised by semi-abstract art and bright colours, which they considered as a form of resistance to the Nazis.

Pablo Picasso showed two works: a pair of etchings entitled The Dream and Lie of Franco, 1937, and his monumental painting, Guernica, 1937.

The involvement of a non-Spanish artist was also an important statement in an era dominated by the rise of nationalism, both in democratic and totalitarian regimes.

Thus for the poster artist the simple question of expressing his own sensibility and emotion is neither legitimate nor practically realizable, if not in the service of an objective goal.

[13]” And the French author, Louis Aragon, declared in 1936: “For artists as for every person who feels like a spokesperson for a new humanity, the Spanish flames and blood put Realism on the agenda.

The series The Year of Peril, created in 1942 by the American artist Thomas Hart Benton, illustrates how the boundary between art and propaganda can be blurred by such a stance.

Produced as a reaction to the bombing of Pearl Harbor by the Japanese army in 1941, the series portrayed the threat posed to the U.S. by Nazism and Fascism in an expressive but representational style.

These images were massively reproduced and disseminated in order to contribute to raise support for the U.S. involvement in World War II.

Art had similarly followed the free expression at the heart of modernism, but political appropriation was already sought [as in the left-wing Artists' International Association founded in 1933].

[citation needed] A significant influence was the choice of Sir Kenneth Clark as instigator and director of WAAC, as he believed that the first duty of an artist was to produce good works of art that would bring international renown.

And he believed the second duty was to produce images through which a country presents itself to the world, and a record of war more expressive than a camera may give.

Some depictions could be too realistic and were censored because they revealed sensitive information or would have scared people – and maintaining the nation's morale was vital.

[citation needed] Despite these restrictions, the work commissioned was illustrative, non-bombastic, and often of great distinction thanks to established artists such as Paul Nash, John Piper, Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland and Stanley Spencer.

[citation needed] In terms of subject matters, the images created in concentration and extermination camps are characterised by their determination to enhance the detainees’ dignity and individuality.

Whereas the Nazi extermination machine aimed at dehumanising the internees, creating “faceless” beings, clandestine artists would give them back their individuality.

Rather, it is after the liberation, in the art of survivors that the most brutal and abominable aspects of concentration and extermination camps found a visual expression.

Thus, since the liberation of the camps, artists who have wanted to express the Holocaust in their art have often chosen abstraction or symbolism, thus avoided any explicit representations.