Art of El Greco

[3] El Greco was disdained by the immediate generations after his death because his work was opposed in many respects to the principles of the early baroque style which came to the fore near the beginning of the 17th century and soon supplanted the last surviving traits of the 16th-century Mannerism.

On the one hand, Théophile Gautier, a French poet, dramatist, novelist, journalist and literary critic, believed that El Greco went mad from excessive artistic sensitivity.

[10] Julius Meier-Graefe, a scholar of French Impressionism, travelled in Spain in 1908 and wrote down his experiences in The Spanische Reise, the first book which established El Greco as a great painter of the past.

[10] To the English artist and critic Roger Fry in 1920, El Greco was the archetypal genius who did as he thought best "with complete indifference to what effect the right expression might have on the public".

Fry described El Greco as "an old master who is not merely modern, but actually appears a good many steps ahead of us, turning back to show us the way".

Doctors August Goldschmidt and Germán Beritens argued that El Greco painted such elongated human figures because he had vision problems (possibly progressive astigmatism or strabismus) that made him see bodies longer than they were, and at an angle to the perpendicular.

[14] Stuart Anstis, Professor at the University of California (Department of Psychology) concludes that "even if El Greco were astigmatic, he would have adapted to it, and his figures, whether drawn from memory or life, would have had normal proportions.

[4] Comparative morphological analyses of the two painters revealed their common elements, such as the distortion of the human body, the reddish and (in appearance only) unworked backgrounds, the similarities in the rendering of space etc.

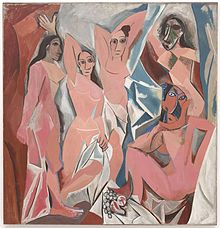

[21] The Symbolists, and Pablo Picasso during his blue period, drew on the cold tonality of El Greco, utilizing the anatomy of his ascetic figures.

[22] The relation between Les Demoiselles d'Avignon and the Opening of the Fifth Seal was pinpointed in the early 1980s, when the stylistic similarities and the relationship between the motifs of both works were analysed.

[23] According to art historian John Richardson Les Demoiselles d'Avignon "turns out to have a few more answers to give once we realize that the painting owes at least as much to El Greco as Cézanne".

[26] Foundoulaki asserts that Picasso "completed ... the process for the activation of the painterly values of El Greco which had been started by Manet and carried on by Cézanne".

Kysa Johnson used El Greco's paintings of the Immaculate Conception as the compositional framework for some of her works, and the master's anatomical distortions are somewhat reflected in Fritz Chesnut's portraits.

"[33] Pacheco asserts that "El Greco believed in constant repainting and retouching in order to make the broad masses tell flat as in nature".

[36] Nicholas Penny, senior curator at the National Gallery of Art in Washington, asserts that "once in Spain, El Greco was able to create a style of his own – one that disavowed most of the descriptive ambitions of painting".

According to Pacheco, El Greco's perturbed, violent and at times seemingly careless-in-execution art was due to a studied effort to acquire a freedom of style.

For example, for the Virgin of the Immaculate Conception that he painted for the side-chapel of Isabella Oballe in the church of Saint Vincent in Toledo (1607–1613), El Greco asked to lengthen the altarpiece itself by another 1.5 feet "because in this way the form will be perfect and not reduced, which is the worst thing that can happen to a figure'".

[39] A significant innovation of El Greco's mature works is the interweaving between form and space; a reciprocal relationship is developed between them which completely unifies the painting surface.

[40] Fernando Marias and Agustín Bustamante García, the scholars who transcribed El Greco's handwritten notes, connect the power that the painter gives to light with the ideas underlying Christian Neo-Platonism.

In The Vision of Saint John and the Fifth Seal of the Apocalypse the scenes owe their power to this otherworldly stormy light, which reveals their mystic character.

The same scholar believes that in El Greco's mature works "the devotional intensity of mood reflects the religious spirit of Roman Catholic Spain in the period of the Counter-Reformation".

In other paintings, this central cylinder of open space is very prominent, providing a distinctive visionary style, due to the deep insights of the pious painter.

[47] Based on the notes written in El Greco's own hand and on his unique style, they see an organic continuity between Byzantine painting and his art.

[49] In this judgement, Mayer disagrees with Oxford University professors, Cyril Mango and Elizabeth Jeffreys, who assert that "despite claims to the contrary, the only Byzantine element of his famous paintings was his signature in Greek lettering".

[51] The Welsh art historian David Davies seeks the roots of El Greco's style in the intellectual sources of his Greek-Christian education and in the world of his recollections from the liturgical and ceremonial aspect of the Eastern Orthodox Church.

[52] Additionally, he asserts that the philosophies of Platonism and ancient Neo-Platonism, the works of Plotinus and Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite, and the texts of the Church fathers and the liturgy offer the keys to the understanding of El Greco's style.

[53] According to Lambraki-Plaka "far from the influence of Italy, in a neutral place which was intellectually similar to his birthplace, Candia, the Byzantine elements of his education emerged and played a catalytic role in the new conception of the image which is presented to us in his mature work".

[54] According to Lambraki-Plaka, El Greco employed a deliberately non-naturalistic style and his completely spiritualized figures are a reference to the ascetics of Byzantine hagiography.

[57] For Espolio the master designed the original altar of gilded wood which has been destroyed, but his small, sculptured group of the Miracle of St. Ildefonso still survives on the lower centre of the frame.