Temple of Artemis

The next, greatest, and last form of the temple, funded by the Ephesians themselves, is described in Antipater of Sidon's list of the world's Seven Wonders: I have set eyes on the wall of lofty Babylon on which is a road for chariots, and the statue of Zeus by the Alpheus, and the hanging gardens, and the colossus of the Sun, and the huge labour of the high pyramids, and the vast tomb of Mausolus; but when I saw the house of Artemis that mounted to the clouds, those other marvels lost their brilliancy, and I said, "Lo, apart from Olympus, the Sun never looked on aught so grand".

Re-excavations in 1987–1988 and re-appraisal of Hogarth's account[a] confirmed that the site was occupied as early as the Bronze Age, with a sequence of pottery finds that extend forward to Middle Geometric times, when a peripteral temple with a floor of hard-packed clay was constructed in the second half of the 8th century BC.

In the 7th century BC, a flood[4] destroyed the temple, depositing over half a meter of sand and flotsam over the original clay floor.

Among the flood debris were the remains of a carved ivory plaque of a griffin and the Tree of Life, apparently North Syrian, and some drilled tear-shaped amber drops of elliptical cross-section.

Bammer notes that though the site was prone to flooding, and raised by silt deposits about two metres between the 8th and 6th centuries, and a further 2.4 m between the sixth and the fourth, its continued use "indicates that maintaining the identity of the actual location played an important role in the sacred organization".

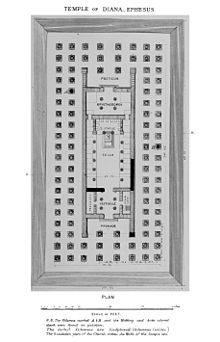

Its peripteral columns stood some 13 m (40 ft) high, in double rows that formed a wide ceremonial passage around the cella that housed the goddess's cult image.

Pliny the Elder, seemingly unaware of the ancient continuity of the sacred site, claims that the new temple's architects chose to build it on marshy ground as a precaution against earthquakes, with lower foundation layers of fleeces and pounded charcoal.

[10] The temple became an important attraction, visited by merchants, kings, and sightseers, many of whom paid homage to Artemis in the form of jewelry and various goods.

[11] Diogenes Laertius claims that the misanthropic philosopher Heraclitus, thoroughly disapproving of civil life at Ephesus, played knucklebones in the temple with the boys, and later deposited his writings there.

Stefan Karweise notes that any arsonist would have needed access to the wooden roof framing;[17](p 57) Knibbe (1998) writes of an "entire corps" of attested temple guards and custodians.

Literary sources describe the temple's adornment by paintings, columns gilded with gold and silver, and religious works of renowned Greek sculptors Polyclitus, Pheidias, Cresilas, and Phradmon.

[f] In 268 AD, according to Jordanes,[26] a raid by the Goths, under their leaders "Respa, Veduc, and Thurar",[g][h] "laid waste many populous cities and set fire to the renowned temple of Diana at Ephesus.

"[26] The extent and severity of the damage are unknown; the temple may have been repaired and open to us again, or it may have lain derelict until its official closure during the persecution of pagans in the late Roman Empire.

[30] A legend of the Late Middle Ages claims that some of the columns in the Hagia Sophia were taken from the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus, but there is no truth to this story.

[31][32] The main primary sources for the Temple of Artemis at Ephesus are Pliny the Elder's Natural History,[33] writings by Pomponius Mela,[34] and Plutarch's Life of Alexander.

[37] In addition, the museum has part of possibly the oldest cache of coins in the world (600 BC) that had been buried in the foundations of the Archaic temple.

The literary accounts that describe it as "Amazonian" refer to the later founder-myths of Greek émigrés who developed the cult and temple of Artemis Ephesia.

At Ephesus, a goddess whom the Greeks associated with Artemis was venerated in an archaic, pre-Hellenic cult image[47] that was carved of wood (a xoanon) and kept decorated with jewelry.

[47] The traditional interpretation of the oval objects covering the upper part of the Ephesian Artemis is that they represent multiple breasts, symbolizing her fertility.

In some versions of the statue, the goddess' skin has been painted black, likely to emulate the aged wood of the original, while her clothes and regalia, including the so-called "breasts", were left unpainted or cast in different colors.

[48][page needed] Fleischer (1973) suggested that instead of breasts, the oval objects were decorations that would have been hung ceremonially on the original wood statue (possibly eggs, or the testicles of sacrificed bulls[49]), and which were incorporated as carved features on later copies.

[48][page needed] The "breasts" of the Lady of Ephesus, it now appears, were likely based on amber gourd-shaped drops, elliptical in cross-section and drilled for hanging, that were rediscovered in the archaeological excavations of 1987–1988.

[k][54] A votive inscription mentioned by Bennett (1912),[55] which dates probably from about the 3rd century BC, associates Ephesian Artemis with Crete: The Greek habits of syncretism assimilated all foreign gods under some form of the Olympian pantheon familiar to them – the interpretatio graeca – and it is clear that at Ephesus, the identification with Artemis that the Ionian settlers made of the "Lady of Ephesus" was slender.