Artemy Vedel

He produced works based on Ukrainian folk melodies, and made an important contribution in the music history of Ukraine.

His fortunes declined when the cultural life of Kharkiv was affected by decrees issued by Tsar Paul I of Russia.

The monastery's authorities discovered handwritten threats towards the Russian royal family, and accused Vedel of writing them.

The character of Russian and Ukrainian worship derives from performances of the znamenny chant, which developed a tradition that was characterised by seamless melodies and a capacity to sustain pitch.

[7] In the early 19th century, music in West-European was making the transition from classical to predominantly Romantic, having earlier shifted away from the Baroque style.

The early part of the 19th century was a period that marked a low ebb in the fortunes of traditional Russian music.

Bortniansky studied in Venice before eventually becoming the director of music at the court chapel in St Petersburg in 1801.

Under him, the Imperial Court Chapel expanded its role so it influenced, and eventually controlled, church choral singing throughout the Russian Empire.

[7][9] Vedel followed Bortniansky in combining the Italian Baroque style to ancient Russian hymnody,[7] at a time when classical influences were being introduced into Ukrainian choral music, such as four-voice polyphony, the soloist and the choir singing at different alternative times, and the employment of three or four sections in a work.

Today, advocates of Vedel such as Mykola Hobdych, the director of the Kyiv Chamber Choir, and the musicologist Tetyana Husarchuk, continue to research and popularise his music.

[11] The task of studying Vedel is made more difficult for historians and musicologists because of the fragmentary and superficial nature of the sources—information about his methods is lacking, and his works cannot always be accurately dated.

[19] He studied at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, where his teachers included the Italian Giuseppe Sarti,[20] who spent 18 years as an operatic composer in the Russian Empire.

It was at that time the oldest and most influential higher education institution in the Russian Empire; most of the country's leading academics were originally graduates of the academy.

[19] In 1788 Vedel, along with other choristers, was sent by Samuel Myslavsky [uk], the Metropolitan of Kyiv and Halych, and the rector of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy, to Moscow.

[14] There he served as the assistant choir master and a violinist for Pyotr Dmitrievich Yeropkin [ru], the Governor-General of Moscow,[20] and, after 1790, by his successor, Alexander Prozorovsky.

Among the famous choirs in the city at that time was one belonging to General Andrei Levanidov at the Kyiv headquarters of the Ukrainian infantry regiment.

[23] The music class at the Kharkiv Collegium was first recorded in 1798, when in January that year two canons and a choral concerto by Vedel were performed.

He distributed his belongings (including all his manuscripts),[19] and the end of the summer of 1798 he returned to live at his parents' house in Kyiv.

[14] Early in 1799, frustrated by the lack of opportunities to compose and teach and possibly suffering from a form of mental illness, Vedel enrolled as a novice monk at the Kyiv Pechersk Lavra.

[31] After the death of Paul I in 1801, the new tsar, Alexander I, proclaimed an amnesty for unjustly imprisoned convicts, and many prisoners were released.

[19] In 1808, after nine years' imprisonment, and by now mortally ill, Vedel was allowed to return home to his father's house in Kyiv.

[19] His friend Ioann Levanda [uk] (the archpriest of Kyiv Cathedral and a well-known preacher) obtained permission for a decent funeral, an indication that Vedel was considered by the government "to be untrustworthy for the rest of his life".

[19] His letters to Turchaninov reveal a care for oppressed people—reflected in his choice of themes for his concertos—as well as an opposition towards serfdom, which had been established in Ukraine by Catherine the Great.

[13][note 6] At least 80 of his compositions have been identified, including 31 choral concertos and six trios, two liturgies, an all-night vigil,[13][14] and three irmos cycles.

[19][36] The musicologists Ihor Sonevytsky and Marko Robert Stech consider Vedel to be the archetypal composer of Ukrainian music from the Baroque era.

[6] Vedel was considered during his lifetime to be a traditional and conservative composer, in contrast to his older contemporaries Berezovsky and Bortniansky.

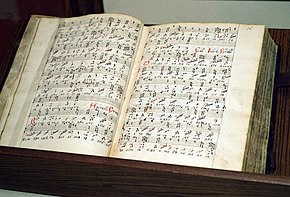

[14] Hand-written variations of Vedel's music appeared,[12] but conductors amended scores to make them more suitable for unauthorised performances.

The most important studies about Vedel produced in 19th and early 20th centuries belonged to musicologists as Askochensky, Vasily Metalov [ru], Vladimir Stasov, and Pyotr Turchaninov.

According to the ethnomusicologist Taras Filenko, "His free command of contemporary techniques of choral writing, combined with innovations in adapting the particularities of Ukrainian melody, make Artem Vedel's works a unique phenomenon in the context of world musical culture.

"[45] According to Chekan, Vedel's texture is "at times monumental and at others subtly contrasted, strikingly showing the possibilities of the a cappella sound".