Arthur C. Clarke

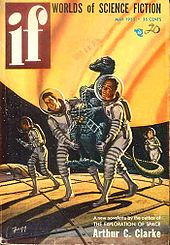

[6] His science fiction writings in particular earned him a number of Hugo and Nebula awards, which along with a large readership, made him one of the towering figures of the genre.

Clarke attributed his interest in science fiction to reading three items: the November 1928 issue of Amazing Stories in 1929; Last and First Men by Olaf Stapledon in 1930; and The Conquest of Space by David Lasser in 1931.

Clarke also contributed pieces to the "Debates and Discussions Corner", a counterpoint to a Urania article offering the case against space travel, and also his recollections of the Walt Disney film Fantasia.

Clarke spent most of his wartime service working on ground-controlled approach (GCA) radar, as documented in the semiautobiographical Glide Path, his only non-science fiction novel.

[28] His 1951 book, The Exploration of Space, was used by the rocket pioneer Wernher von Braun to convince President John F. Kennedy that it was possible to go to the Moon.

[36] He was held in such high esteem that when fellow science fiction writer Robert A. Heinlein came to visit, the Sri Lanka Air Force provided a helicopter to take them around the country.

"[48] In his obituary, Clarke's friend Kerry O'Quinn wrote: "Yes, Arthur was gay ... As Isaac Asimov once told me, 'I think he simply found he preferred men.'

[57] Clarke himself said, "I take an extremely dim view of people mucking about with boys", and Rupert Murdoch promised him the reporters responsible would never work in Fleet Street again.

Although he and his home were unharmed by the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake tsunami, his "Arthur C. Clarke Diving School" (now called "Underwater Safaris")[59] at Hikkaduwa near Galle was destroyed.

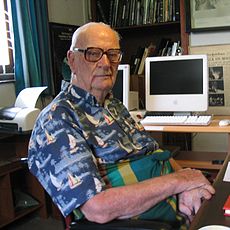

[61] Because of his post-polio deficits, which limited his ability to travel and gave him halting speech, most of Clarke's communications in his last years were in the form of recorded addresses.

In September 2007, he provided a video greeting for NASA's Cassini probe's flyby of Iapetus (which plays an important role in the book of 2001: A Space Odyssey).

[69][70] American Atheist Magazine wrote of the idea: "It would be a fitting tribute to a man who contributed so much, and helped lift our eyes and our minds to a cosmos once thought to be province only of gods.

During this time, Clarke corresponded with C. S. Lewis in the 1940s and 1950s and they once met in an Oxford pub, the Eastgate, to discuss science fiction and space travel.

Clarke voiced great praise for Lewis upon his death, saying The Ransom Trilogy was one of the few works of science fiction that should be considered literature.

[84] Later, at the home of Larry Niven in California, a concerned Heinlein attacked Clarke's views on United States foreign and space policy (especially the SDI), vigorously advocating a strong defence posture.

The whereabouts of astronaut Dave Bowman (the "Star Child"), the artificial intelligence HAL 9000, and the development of native life on Europa, protected by the alien Monolith, are revealed.

James Randi later recounted that upon seeing the premiere of 2001, Clarke left the theatre at the intermission in tears, after having watched an eleven-minute scene (which did not make it into general release) where an astronaut is doing nothing more than jogging inside the spaceship, which was Kubrick's idea of showing the audience how boring space travels could be.

[87] Titled The Odyssey File: The Making of 2010, and co-authored with Hyams, it illustrates his fascination with the then-pioneering medium of email and its use for them to communicate on an almost daily basis at the time of planning and production of the film while living on opposite sides of the world.

Later, in the hospital scene with David Bowman's mother, an image of the cover of Time portrays Clarke as the American President and Kubrick as the Soviet Premier.

[90] After years of no progress, Fincher stated in an interview in late 2007 (in which he also opined the novel as being influential on the films Alien and Star Trek: The Motion Picture) that he is still attached to the project.

In a 1959 essay, Clarke predicted global satellite TV broadcasts that would cross national boundaries indiscriminately and would bring hundreds of channels available anywhere in the world.

According to John R. Pierce, of Bell Labs, who was involved in the Echo satellite and Telstar projects, he gave a talk upon the subject in 1954 (published in 1955), using ideas that were "in the air", but was not aware of Clarke's article at the time.

For example, the concept of geostationary satellites was described in Hermann Oberth's 1923 book Die Rakete zu den Planetenräumen (The Rocket into Interplanetary Space), and then the idea of radio communication by means of those satellites in Herman Potočnik's (written under the pseudonym Hermann Noordung) 1928 book Das Problem der Befahrung des Weltraums – [106]), sections: Providing for Long Distance Communications and Safety,[d] and (possibly referring to the idea of relaying messages via satellite, but not that three would be optimal) Observing and Researching the Earth's Surface, published in Berlin.

In 1956, while scuba diving, Wilson and Clarke uncovered ruined masonry, architecture, and idol images of the sunken original Koneswaram temple – including carved columns with flower insignia, and stones in the form of elephant heads – spread on the shallow surrounding seabed.

The ship, ultimately identified as belonging to the Mughal Emperor, Aurangzeb, yielded fused bags of silver rupees, cannon, and other artefacts, carefully documented, became the basis for The Treasure of the Great Reef.

[115] When he entered the Royal Air Force, Clarke insisted that his dog tags be marked "pantheist" rather than the default, Church of England,[44] and in a 1991 essay entitled "Credo", described himself as a logical positivist from the age of 10.

"[126] Clarke also wrote, "It is not easy to see how the more extreme forms of nationalism can long survive when men have seen the Earth in its true perspective as a single small globe against the stars.

Our technology must still be laughably primitive; we may well be like jungle savages listening for the throbbing of tom-toms, while the ether around them carries more words per second than they could utter in a lifetime.

[44] Similarly, in the prologue to the 1990 Del Rey edition of Childhood's End, he writes "...after ... researching my Mysterious World and Strange Powers programmes, I am an almost total skeptic.

Topics examined ranged from ancient, man-made artifacts with obscure origins (e.g., the Nazca lines or Stonehenge), to cryptids (purported animals unknown to science), or obsolete scientific theories that came to have alternate explanations (e.g., Martian canals).