Ascomycota

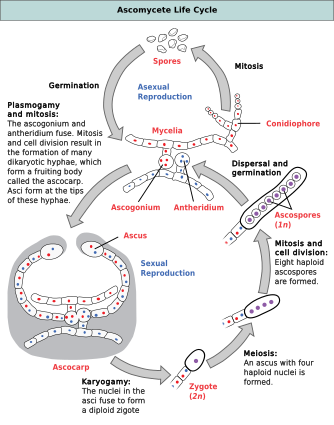

[3] The defining feature of this fungal group is the "ascus" (from Ancient Greek ἀσκός (askós) 'sac, wineskin'), a microscopic sexual structure in which nonmotile spores, called ascospores, are formed.

Examples of ascomycetes include Penicillium species on cheeses and those producing antibiotics for treating bacterial infectious diseases.

The many plant-pathogenic ascomycetes include apple scab, rice blast, the ergot fungi, black knot, and the powdery mildews.

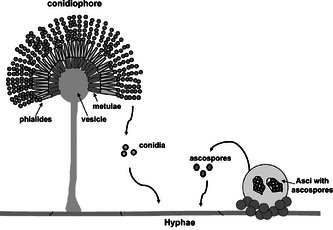

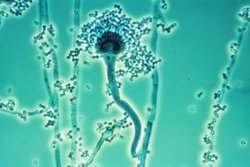

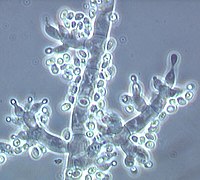

The conidiospores commonly contain one nucleus and are products of mitotic cell divisions and thus are sometimes called mitospores, which are genetically identical to the mycelium from which they originate.

Where recent molecular analyses have identified close relationships with ascus-bearing taxa, anamorphic species have been grouped into the Ascomycota, despite the absence of the defining ascus.

Species of the Deuteromycota were classified as Coelomycetes if they produced their conidia in minute flask- or saucer-shaped conidiomata, known technically as pycnidia and acervuli.

[9] The Hyphomycetes were those species where the conidiophores (i.e., the hyphal structures that carry conidia-forming cells at the end) are free or loosely organized.

Many interconnected hyphae form a thallus usually referred to as the mycelium, which—when visible to the naked eye (macroscopic)—is commonly called mold.

Ascocarps come in a very large variety of shapes: cup-shaped, club-shaped, potato-like, spongy, seed-like, oozing and pimple-like, coral-like, nit-like, golf-ball-shaped, perforated tennis ball-like, cushion-shaped, plated and feathered in miniature (Laboulbeniales), microscopic classic Greek shield-shaped, stalked or sessile.

Their texture can likewise be very variable, including fleshy, like charcoal (carbonaceous), leathery, rubbery, gelatinous, slimy, powdery, or cob-web-like.

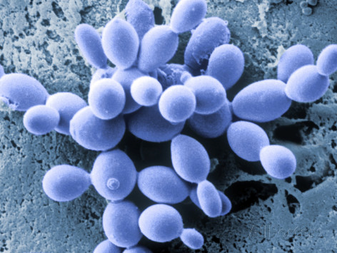

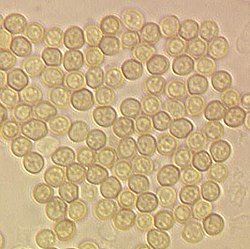

Some ascomyceous fungi, such as Saccharomyces cerevisiae, grow as single-celled yeasts, which—during sexual reproduction—develop into an ascus, and do not form fruiting bodies.

Except for lichens, the non-reproductive (vegetative) mycelium of most ascomycetes is usually inconspicuous because it is commonly embedded in the substrate, such as soil, or grows on or inside a living host, and only the ascoma may be seen when fruiting.

Pigmentation, such as melanin in hyphal walls, along with prolific growth on surfaces can result in visible mold colonies; examples include Cladosporium species, which form black spots on bathroom caulking and other moist areas.

[11] Asci of Ascosphaera fill honey bee larvae and pupae causing mummification with a chalk-like appearance, hence the name "chalkbrood".

[12] Yeasts for small colonies in vitro and in vivo, and excessive growth of Candida species in the mouth or vagina causes "thrush", a form of candidiasis.

The septa commonly have a small opening in the center, which functions as a cytoplasmic connection between adjacent cells, also sometimes allowing cell-to-cell movement of nuclei within a hypha.

To obtain these nutrients from their surroundings, ascomycetous fungi secrete powerful digestive enzymes that break down organic substances into smaller molecules, which are then taken up into the cell.

Several species colonize plants, animals, or other fungi as parasites or mutualistic symbionts and derive all their metabolic energy in form of nutrients from the tissues of their hosts.

Many Ascomycota engage in symbiotic relationships such as in lichens—symbiotic associations with green algae or cyanobacteria—in which the fungal symbiont directly obtains products of photosynthesis.

The distribution of species is variable; while some are found on all continents, others, as for example the white truffle Tuber magnatum, only occur in isolated locations in Italy and Eastern Europe.

The conidiospores commonly contain one nucleus and are products of mitotic cell divisions and thus are sometimes called mitospores, which are genetically identical to the mycelium from which they originate.

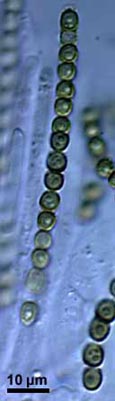

In staurospores ray-like arms radiate from a central body; in others (helicospores) the entire spore is wound up in a spiral like a spring.

These two basic types can be further classified as follows: Sometimes the conidia are produced in structures visible to the naked eye, which help to distribute the spores.

Fusion of the nuclei (karyogamy) takes place in the U-shaped cells in the hymenium, and results in the formation of a diploid zygote.

The nuclei along with some cytoplasma become enclosed within membranes and a cell wall to give rise to ascospores that are aligned inside the ascus like peas in a pod.

The fruiting bodies of the Ascomycota provide food for many animals ranging from insects and slugs and snails (Gastropoda) to rodents and larger mammals such as deer and wild boars.

These mutualistic associations are commonly known as lichens, and can grow and persist in terrestrial regions of the earth that are inhospitable to other organisms and characterized by extremes in temperature and humidity, including the Arctic, the Antarctic, deserts, and mountaintops.

While the photoautotrophic algal partner generates metabolic energy through photosynthesis, the fungus offers a stable, supportive matrix and protects cells from radiation and dehydration.

The fine mycelial network of the fungus enables the increased uptake of mineral salts that occur at low levels in the soil.

The exact nature of the relationship between endophytic fungus and host depends on the species involved, and in some cases fungal colonization of plants can bestow a higher resistance against insects, roundworms (nematodes), and bacteria; in the case of grass endophytes the fungal symbiont produces poisonous alkaloids, which can affect the health of plant-eating (herbivorous) mammals and deter or kill insect herbivores.