Asherah

The majority of scholars hold that Yahweh and Asherah were a consort pair in ancient Israel and Judah,[7][8][9][10] while others disagree.

[11][12][13] Some have sought a common-noun meaning of her name, especially in Ugaritic appellation rabat athirat yam, only found in the Baal Cycle.

There is no hypothesis for rabat athirat yam without significant issues, and if Asherah were a word from Ugarit it would be pronounced differently.

Her titles often include qdš "holy" and baʽlat, or rbt "lady",[20][21] and qnyt ỉlm, "progenitress of the gods.

An especially common Asherah tree in visual art is the date palm, a reliable producer of nutrition through the year.

[41] Many times, Asherah's pubis area was marked by a concentration of dots, indicating pubic hair,[42] though this figure is sometimes polysemically understood as a grape cluster.

"[45] The lioness made a ubiquitous symbol for goddesses of the ancient Middle East that was similar to the dove[46][page needed] and the tree.

[46][page needed] The symbols around Asherah are so many (8+ pointed star, caprids and the like, along with lunisolar, arboreal, florid, serpentine) that a listing would approach meaninglessness as it neared exhaustiveness.

In it, he complements her as "lord of the mountain" (bel shadī), and presages similar use with words like voluptuousness, joy, tender, patient, mercy to commemorate setting up a "protective genius" (font?)

[49] Though it is accepted that Ashratum's name is cognate to that of Asherah, the two goddesses are not actually identified with one another, given that they occupied different positions within their pantheons, despite sharing their status as consort to the supreme deity.

[50][page needed] In Akkadian texts, Asherah appears as Aširatu; though her exact role in the pantheon is unclear; as a separate goddess, Antu, was considered the wife of Anu, the god of Heaven.

In contrast, ʿAshtart is believed to be linked to the Mesopotamian goddess Ishtar who is sometimes portrayed as the daughter of Anu.

[51] Points of reference in Akkadian epigraphy are collocated and heterographic Amarna Letters 60 and 61's Asheratic personal name.

[59] This solution was a response to and variation of B. Margalit's of her following in Yahweh's literal footsteps, a less generous estimation nonetheless supported by DULAT's use of the Ugaritian word in an ordinary sense.

[60] The common Semitic root ywm (for reconstructed Proto-Semitic *yawm-),[61] from which derives (Hebrew: יוֹם), meaning "day", appears in several instances in the Masoretic Texts with the second-root letter (-w-) having been dropped, and in a select few cases, replaced with an A-class vowel of the Niqqud,[62] resulting in the word becoming y(a)m. Such occurrences, as well as the fact that the plural, "days", can be read as both yōmîm and yāmîm (Hebrew: יָמִים), gives credence to this alternate translation.

"[74] However, a number of scholars hold that the "asherah" mentioned in the inscriptions refers to some kind of cultic object or symbol, rather than a goddess.

[80][full citation needed] It's such a common motif in Syrian and Phoenician ivories that the Arslan Tash horde had at least four; they can be seen in the Louvre.

[84] The Hebrew Bible frequently and graphically associates goddess worship with prostitution ("whoredom") in material written after the reforms of Josiah.

Although their nature remains uncertain, sexual rites typically revolved around women of power and influence, such as Maacah.

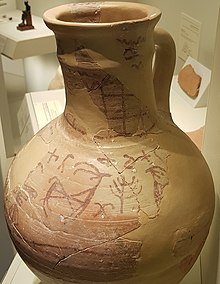

"[94] Various partial inscriptions found on destroyed seventh century BCE jars in Ekron contain words like šmn "oil", dbl "fig cake", qdš "holy," l'šrt "to Asherah", and lmqm "for the shrine".

Beginning during the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, a Semitic goddess named Qetesh ("holiness", sometimes reconstructed as Qudshu) appears prominently.

It is unclear whether the name would be an Aramaic vocalisation of the Ugaritic ʾAṯirat or a later borrowing of the Hebrew ʾĂšērāh or similar form.

[101]"[102] Asherah survived late in remote South Arabia as seen in some common era Qatabanian and Maʕinian inscriptions.

[103] The Ugaritic texts reveal significant parallels between the goddesses Athirat and Shapshu, suggesting a possible identification.

Both are referred to as "The Lady" (rbt), a title signifying supreme authority in the pantheon, and they are described as mothers of the gods, key figures in creation, and central to maintaining cosmic order.

[105] Another significant reason for this conflation would be a passage found in Ugaritic inscription K1.23 which describes the myth known as The Gracious and Most Beautiful Gods.

In this text, twins Shahar (dawn) and Shalim (dusk) are described as offspring of El through two women he meets at the seashore.