Greco-Turkish War (1919–1922)

[47] These included Eastern Thrace, the islands of Imbros (İmroz, since 29 July 1979 Gökçeada) and Tenedos (Bozcaada), and parts of western Anatolia around the city of Smyrna, which contained sizable ethnic Greek populations.

[64] The United Kingdom had hoped that strategic considerations might persuade Constantine to join the cause of the Allies, but the King and his supporters insisted on strict neutrality, especially whilst the outcome of the conflict was hard to predict.

This enmity inevitably spread throughout Greek society, creating a deep rift that contributed decisively to the failed Asia Minor campaign and resulted in much social unrest in the inter-war years.

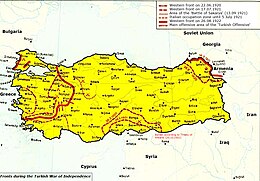

[75][76][77] In October 1920, the Greek army advanced further east into Anatolia, with the encouragement of Lloyd George, who intended to increase pressure on the Turkish and Ottoman governments to sign the Treaty of Sèvres.

Churchill said: "The Greek columns trailed along the country roads passing safely through many ugly defiles, and at their approach the Turks, under strong and sagacious leadership, vanished into the recesses of Anatolia.

"[78] During October 1920, King Alexander, who had been installed on the Greek throne on 11 June 1917 when his father Constantine was pushed into exile by the Venizelists, was bitten by a monkey kept at the Royal Gardens and died within days from sepsis.

In early 1921 they resumed their advance with small scale reconnaissance incursions that met stiff resistance from entrenched Turkish Nationalists, who were increasingly better prepared and equipped as a regular army.

[91] Between 27 June and 20 July 1921, a reinforced Greek army of nine divisions launched a major offensive, the greatest thus far, against the Turkish troops commanded by İsmet İnönü on the line of Afyonkarahisar-Kütahya-Eskişehir.

The state and Army leadership, including King Constantine, Prime Minister Dimitrios Gounaris, and General Anastasios Papoulas, met at Kütahya where they debated the future of the campaign.

The Greeks, with their faltering morale rejuvenated, failed to appraise the strategic situation that favoured the defending side; instead, pressed for a 'final solution', the leadership was polarised into the risky decision to pursue the Turks and attack their last line of defence close to Ankara.

[93] Meanwhile, the Turkish parliament, not happy with the performance of İsmet İnönü as the Commander of the Western Front, wanted Mustafa Kemal and Chief of General Staff Fevzi Çakmak to take control.

Some of the removed Venizelist officers organised a movement of "National Defense" and planned a coup to secede from Athens, but never gained Venizelos's endorsement and all their actions remained fruitless.

[108][109] After re-capturing Smyrna, Turkish forces headed north for the Bosporus, the sea of Marmara, and the Dardanelles where the Allied garrisons were reinforced by British, French and Italian troops from Constantinople.

They were all armed and later proved to be Kemalist officers sent over to organize the Turkish population in the suburbs in case of an attack on Constantinople"The British cabinet initially decided to resist the Turks if necessary at the Dardanelles and to ask for French and Italian help to enable the Greeks to remain in eastern Thrace.

Mustafa Kemal presented himself as revolutionary to the communists, protector of tradition and order to the conservatives, patriot soldier to the nationalists, and a Muslim leader for the religious, so he was able to recruit all Turkish elements and motivate them to fight.

Toynbee also stated that the Turkish troops had clearly, individually and deliberately, burned down each house in these villages, pouring petrol on them and taking care to ensure that they were totally destroyed.

[139] According to a French report in 1918: The miserable men in the labor battalions are dispersed in different directions in the far ends of the Empire, from the shores of Asia Minor and the Black Sea to the Caucasus, Bagdad, Mesopotamia and Egypt; some of them to build military roads, others to dig the tunnels of Bagdad railway...I saw those wretched men in the hospitals of Konya, stretched upon their beds or on the ground, resembling living skeletons, longing for death to end their sufferings...To describe this disastrous situation I shall conclude that as a result of high level of mortality the cemetery of Konya is full of corpses of the soldiers serving in the labor battalions, and in each tomb there lie four, five or sometimes even six corpses just like dogs.

Taner Akçam wrote that according to one newspaper, Nurettin Pasha had proposed the killing of all the remaining Greek and Armenian populations in Anatolia, a suggestion rejected by Mustafa Kemal.

[141] There were also several contemporary Western newspaper articles reporting the atrocities committed by Turkish forces against Christian populations living in Anatolia, mainly Greek and Armenian civilians.

An American newspaper, the Atlanta Observer wrote: "The smell of the burning bodies of women and children in Pontus" said the message "comes as a warning of what is awaiting the Christian in Asia Minor after the withdrawal of the Hellenic army.

[153] US Consul-General George Horton, whose account has been criticised by scholars as anti-Turkish,[154][155][156] claimed, "One of the cleverest statements circulated by the Turkish propagandists is to the effect that the massacred Christians were as bad as their executioners, that it was '50–50'."

[171] A similar atrocity was witnessed by Lieutenant Ali Rıza Akıncı on the morning of 8 September 1922, in the railway station of Saruhanlı, which provoked his units to burn the Greek Soldiers in a nearby barn whom they had taken prisoners.

The report stated that a Muslim woman in the village of Hamidiye, Uzunköprü was hanged upside down in a tree and was burned with the fire below her, while a cat was put inside her underwear while being forced to confess the location of her husband's weapons.

[177] The Inter-Allied commission, consisting of British, French, American, and Italian, officers,[f] and the representative of the Geneva International Red Cross, M. Gehri, prepared two separate collaborative reports on their investigations of the Gemlik-Yalova Peninsula Massacres.

[186] The burning of the entirety of the town of Gördes by the Greek Occupation forces; 431 buildings, was also mentioned in the İsmet Paşa's referendum and Venizelos' reply did not contain a contrary statement to this claim.

Moreover, he tells the story of a fellow doctor-officer Giannis Tzogias during their retreat, who did not stop two Greek soldiers from raping 2 Turkish girls out of fear nor shot nor reported them to their commander Trikoupis.

[189] Also, Şükrü Nail Soysal, a member of Parti Pehlivan's Platoon in his memoirs states that on 10 July 1921 his village, Ortaköy was looted and after being tortured, 40–50 males (including his brother Mehmet) were taken as prisoners and 30 were taken not to be seen again.

Stergiadis immediately punished the Greek soldiers responsible for violence on with court martial and created a commission to decide on payment for victims (made up of representatives from Great Britain, France, Italy and other allies).

[202] Historian of the Middle East, Sydney Nettleton Fisher wrote that: "The Greek army in retreat pursued a burned-earth policy and committed every known outrage against defenceless Turkish villagers in its path.

He also states that the burning happened while the grain was still on the fields, and sums up the atrocities committed by his fellow soldiers with the following words: "there was no lack of deviance and violence by our soldiers" [205] The severity of the war crimes committed by the retreating troops were also mentioned by another officer of the Greek Army in Anatolia, Panagiotis Demestichas, who in his memoirs he writes the following: "The destruction in the cities and villages through which we passed, the arsons and other ugliness, I am not able to describe, and I prefer that the world remains oblivious to this destruction.