Ascalon

Traces of settlement in the area around Ascalon exist from the 3rd millennium BCE, with evidence of city fortifications emerging in the Middle Bronze Age.

The Mamluk sultan Baybars ordered the destruction (slighting) of the city fortifications and the harbour in 1270 to prevent any further military use, though structures such as the Shrine of Husayn's Head survived.

[12][13] In the EB II-III (2900–2500 BCE), the site of Tel Ashkelon served as an important seaport for the trade route between the Old Kingdom of Egypt and Byblos.

[21] The ties between Ashkelon and Egypt in the late 15h century are documented in Papyrus Hermitage 1116A, which is dated to the time of Amenhotep II (1427–1401 BCE).

[24] Their earliest pottery, types of structures and inscriptions are similar to the early Greek urbanised centre at Mycenae in mainland Greece, adding evidence to the conclusion that they were one of the "Sea Peoples" that upset cultures throughout the Eastern Mediterranean at that time.

At that time, Ashkelon controlled several cities in the Yarkon River basin (near modern Tel Aviv, including Beth Dagon, Jaffa, Beneberak and Azor).

The origin of these imports is primarily Phoenicia and the Greek regions of Attica, Corinth and Magna Graecia, as well as Cyprus, Egypt and Mesopotamia.

[3] Archaeological investigation showed that the city was violently destroyed by fire around 290 BCE, some decades after the conquest of the region by Alexander the Great.

In a significant case of an early witch-hunt, during the reign of the Hasmonean queen Salome Alexandra, the court of Simeon ben Shetach sentenced to death eighty women in Ashkelon who had been charged with sorcery.

[45] Herod the Great, who became a client king of the Roman Empire, ruling over Judea and its environs in 30 BCE, had not received Ashkelon, yet he built monumental buildings there: bath houses, elaborate fountains and large colonnades.

Ambrose of Milan (339 - 397) reports that pagans burnt a basilica in Ascalon and the 5th century Christian historian Theodoret recounts atrocities against bishops and women.

Bishop Dionysius, who represented Ascalon at a synod in Jerusalem in 536, was on another occasion called upon to pronounce on the validity of a baptism with sand in waterless desert.

It may have been temporarily occupied by Amr ibn al-As, but definitively surrendered after a siege to Mu'awiya I (who later founded the Umayyad Caliphate) not long after he captured the Byzantine district capital of Caesarea in c. 640.

An inscription found by Charles Clermont-Ganneau in the 19th century indicates that the Abbasid caliph al-Mahdi ordered the construction of a mosque with a minaret in Asqalan in 772.

Islamic geographer Al-Maqdisi (945 – 991) described Ascalon, admiring its fortifications, garrison, mosque and fruits, but also recounted that its port was unsafe.

[9]In 1091, a couple of years after a campaign by grand vizier Badr al-Jamali to reestablish Fatimid control over the region, the head of Husayn ibn Ali (a grandson of the Islamic prophet Muhammad) was "rediscovered", prompting Badr to order the construction of a new mosque and mashhad (shrine or mausoleum) to hold the relic, known as the Shrine of Husayn's Head.

[68] In 1100, Ascalon was among the Fatimid coastal cities (along with Arsuf, Caesarea and Acre) that paid tribute to the crusaders, as part of a short truce.

The Franks won the land battle and it has been recounted that when they encountered the Fatimid fleet in Jaffa, they threw the head of the defeated governor of Ascalon on board of the Egyptian ships, to inform them of the Crusader victory.

In 1134, the Crusader count of Jaffa, Hugh II, rebelled against King Fulk, who accused him of conspiring against his realm, and of intimate relations with his wife.

Hugh II rode to Ascalon to seek help, and the Muslim troops were happy to contribute to the internal feud among the Crusader.

[72] In the time of Fulk, three fortresses were erected around the city, in order to address the threats it imposed on Jerusalem: Beth Gibelin (1135–6), Ibelin (1140) and Blanchgard (1142).

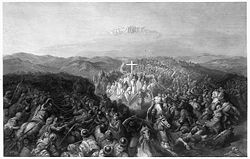

The failure of the Second Crusade and the rise of the Zengid dynasty in Syria motivated Baldwin III of Jerusalem in 1150 to begin preparations to capture Ascalon once and for all.

His stepson Abbas ibn Abi al-Futuh who was involved in his murder then went back to Egypt to be appointed a vizier in his stead, leaving Ascalon without his troops.

[64][74][76] A year after the conquest, Muslim geographer Muhammad al-Idrisi described the city's markets and fortifications, but also the destrcution of its environs, caused by its siege.

[68] In January 1192, crusade leader King Richard the Lionheart of England, proceeded to reconstruct Ascalon's fortifications, an endeavor that lasted four months.

After him, it was Hugh IV, Duke of Burgundy who replaced him and ultimately, Richard of Cornwall oversaw its completion in April 1241, again becoming one of the strongest strongholds in the Mediterranean, with a double wall and series of towers.

In June 1247, after capturing Damascus, the Egyptians dedicated all of the military efforts to Ascalon, and the city fell on 15 October 1247, after an assault headed by Fakhr al-Din ibn al-Shaykh.

[85] By the time of the commissioning of the PEF Survey of Palestine in 1871–77, the interior of Ascalon's ruined perimeter was divided into cultivated fields, interspersed with wells.

[96][97][98][99][100][101][102] In 1991 the ruins of a small ceramic tabernacle was found, containing a finely cast bronze statuette of a bull calf, originally silvered, ten centimetres (4 in) long.

[citation needed] In the 1997 season a cuneiform table fragment was found, being a lexical list containing both Sumerian and Canaanite language columns.