Georgian scripts

Although the systems differ in appearance, their letters share the same names and alphabetical order and are written horizontally from left to right.

Georgian scripts are unique in their appearance and their exact origin has never been established; however, in strictly structural terms, their alphabetical order largely corresponds to the Greek alphabet, with the exception of letters denoting uniquely Georgian sounds, which are grouped at the end.

[8] The alphabet was therefore most probably created between the conversion of Iberia under King Mirian III (326 or 337) and the Bir el Qutt inscriptions of 430.

[3] Professor Levan Chilashvili's dating of fragmented Asomtavruli inscriptions, discovered by him at the ruined town of Nekresi, in Georgia's easternmost province of Kakheti, in the 1980s, to the 1st or 2nd century has not been accepted.

This account is now considered legendary, and is rejected by scholarly consensus, as no archaeological confirmation has been found.

This tradition originates in the works of Koryun, a fifth-century historian and biographer of Mashtots,[14] and has been quoted by Donald Rayfield and James R. Russell,[15][16] but has been rejected by Georgian scholarship and some Western scholars who judge the passage in Koryun unreliable or even a later interpolation.

[3] In his study on the history of the invention of the Armenian alphabet and the life of Mashtots, the Armenian linguist Hrachia Acharian strongly defended Koryun as a reliable source and rejected criticisms of his accounts on the invention of the Georgian script by Mashtots.

[18] Some Western scholars quote Koryun's claims without taking a stance on its validity[19][20] or concede that Armenian clerics, if not Mashtots himself, must have played a role in the creation of the Georgian script.

[13] Recent historiography focuses on greater similarities with the Greek alphabet than in the other Caucasian writing systems, most notably the order and numeric value of letters.

[2][3] Some scholars have also suggested certain pre-Christian Georgian cultural symbols or clan markers as a possible inspiration for particular letters.

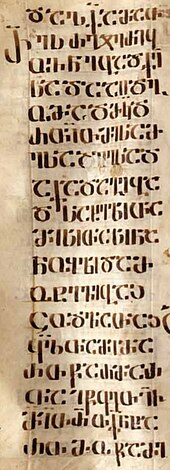

In the majority of 9th-century Georgian manuscripts which were written in Nuskhuri script, Asomtavruli was used for titles and the first letters of chapters.

Georgian linguist and art historian Helen Machavariani believes jani derives from a monogram of Christ, composed of Ⴈ (ini) and Ⴕ (kani).

In the early stages of the development of Nuskhuri texts, Asomtavruli letters were not elaborate and were distinguished principally by size and sometimes by being written in cinnabar ink.

[37] Asomtavruli letter Ⴃ (doni) is often written with decoration effects of fish and birds.

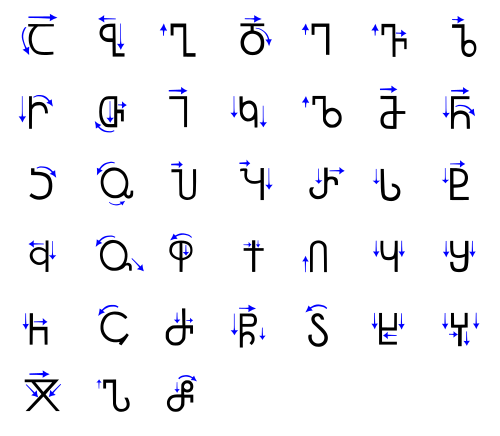

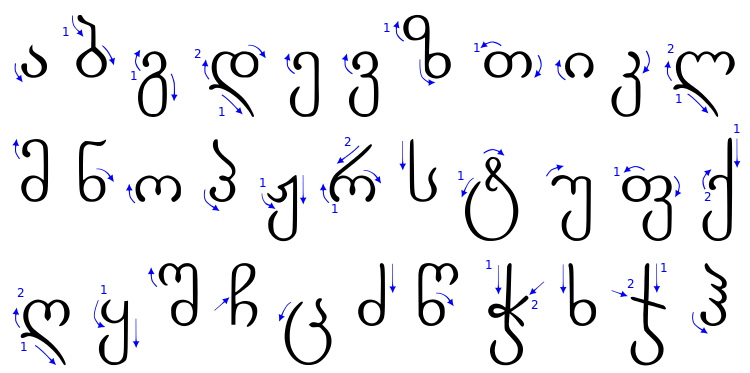

[44] The following table shows the stroke direction of each Nuskhuri letter:[45] Asomtavruli is used intensively in iconography, murals, and exterior design, especially in stone engravings.

The oldest Mkhedruli inscription is found in Ateni Sioni Church dating back to 982 AD.

The second oldest Mkhedruli-written text is found in the 11th-century royal charters of King Bagrat IV of Georgia.

Mkhedruli was mostly used then in the Kingdom of Georgia for the royal charters, historical documents, manuscripts and inscriptions.

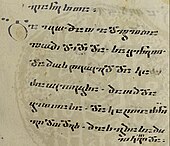

[56] Example of one of the oldest Mkhedruli-written texts found in the royal charter of King Bagrat IV of Georgia, 11th century.

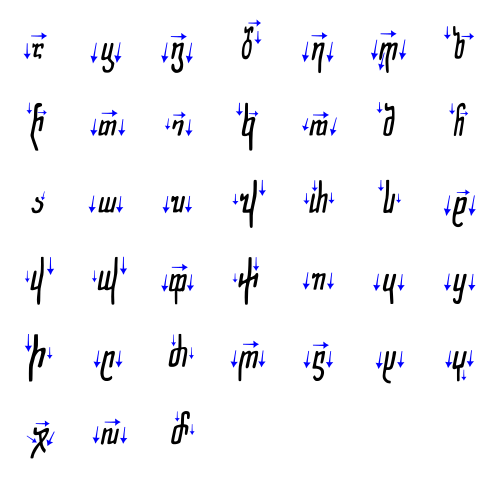

Some of these alphabets retained letters obsolete in Georgian, while others acquired additional letters: The following table shows the stroke order and direction of each Mkhedruli letter:[62][63][64] ზ, ო, and ხ (zeni, oni, khani) are almost always written without the small tick at the end, while the handwritten form of ჯ (jani) often uses a vertical line, (sometimes with a taller ascender, or with a diagonal cross bar); even when it is written at a diagonal, the cross-bar is generally shorter than in print.

Writers readily formed ligatures and abbreviations for nomina sacra, including diacritics called karagma, which resemble titla.

Because writing materials such as vellum were scarce and therefore precious, abbreviating was a practical measure widespread in manuscripts and hagiography by the 11th century.

[66] Mkhedruli, in the 11th to 17th centuries also came to employ digraphs to the point that they were obligatory, requiring adherence to a complex system.

Traditionally, Asomtavruli was used for chapter or section titles, where Latin script might use bold or italic type.

In Asomtavruli and Nuskhuri punctuation, various combinations of dots were used as word dividers and to separate phrases, clauses, and paragraphs.

In the 10th century, clusters of one (·), two (:), three (჻) and six (჻჻) dots (later sometimes small circles) were introduced by Ephrem Mtsire to indicate increasing breaks in the text.

In creating the Georgian Unicode block, important roles were played by German Jost Gippert, a linguist of Kartvelian studies, and American-Irish linguist and script-encoder Michael Everson, who created the Georgian Unicode for the Macintosh systems.

[87] They are capital letters with similar letterforms to Mkhedruli, but with descenders shifted above the baseline, with a wider central oval, and with the top slightly higher than the ascender height.