H. H. Asquith

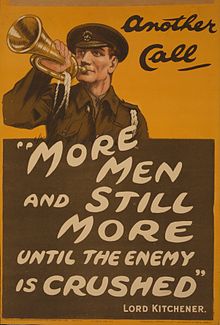

He oversaw national mobilisation, the dispatch of the British Expeditionary Force to the Western Front, the creation of a mass army and the development of an industrial strategy designed to support the country's war aims.

[9] Another biographer, H. C. G. Matthew, writes that Asquith's northern nonconformist background continued to influence him: "It gave him a point of sturdy anti-establishmentarian reference, important to a man whose life in other respects was a long absorption into metropolitanism.

[10] Lloyd George and Churchill were the leading forces in the Liberals' appeal to the voters; Asquith, clearly tired, took to the hustings for a total of two weeks during the campaign, and when the polls began, journeyed to Cannes with such speed that he neglected an engagement with the King, to the monarch's annoyance.

Asquith received inconsistent advice from his Home Secretary, Herbert Gladstone, and successfully pressed the organisers to cancel the religious aspects of the procession, though it cost him the resignation of his only Catholic cabinet minister, Lord Ripon.

He was several times the subject of their tactics: approached (to his annoyance) arriving at 10 Downing Street (by Olive Fargus and Catherine Corbett whom he called 'silly women',[143] confronted at evening parties, accosted on the golf course, and ambushed while driving to Stirling to dedicate a memorial to Campbell-Bannerman.

Retaining Ireland in the Union was the declared intent of all parties, and the Nationalists, as part of the majority that kept Asquith in office, were entitled to seek enactment of their plans for Home Rule, and to expect Liberal and Labour support.

"[160] As the Commons debated the Home Rule bill in late 1912 and early 1913, unionists in the north of Ireland mobilised, with talk of Carson declaring a Provisional Government and Ulster Volunteer Forces (UVF) built around the Orange Lodges, but in the cabinet, only Churchill viewed this with alarm.

With deployment of troops into Ulster imminent and threatening language by Churchill and the Secretary of State for War, John Seely, around sixty army officers, led by Brigadier-General Hubert Gough, announced that they would rather be dismissed from the service than obey.

Tenser relationships with Germany, and that nation moving ahead with its own dreadnoughts, led Reginald McKenna, when Asquith appointed him First Lord of the Admiralty in 1908, to propose the laying down of eight more British ones in the following three years.

"[177] During the continuing escalation Asquith "used all his experience and authority to keep his options open"[178] and adamantly refused to commit his government by saying, "The worst thing we could do would be to announce to the world at the present moment that in no circumstances would we intervene.

[184] On Monday 3 August, the Belgian Government rejected the German demand for free passage through its country and in the afternoon, "with gravity and unexpected eloquence",[183] Grey spoke in the Commons and called for British action "against the unmeasured aggrandisement of any power".

Allied troops established bridgeheads on the Gallipoli Peninsula, but a delay in providing sufficient reinforcements allowed the Turks to regroup, leading to a stalemate Jenkins described "as immobile as that which prevailed on the Western Front".

"[214] The press response was savage: 14 May 1915 saw the publication in The Times of a letter from their correspondent Charles à Court Repington which ascribed the British failure at the Battle of Aubers Ridge to a shortage of high explosive shells.

The Earl of Crawford, who had joined the Government as Minister of Agriculture, described his first Cabinet meeting in these terms: "It was a huge gathering, so big that it is hopeless for more than one or two to express opinions on each detail [...] Asquith somnolent—hands shaky and cheeks pendulous.

"[254] Asquith's achievement in bringing the bill through without breaking up the government was considerable, to quote the estimation of his wife: "Henry's patience and skill in keeping Labour in this amazing change in England have stunned everyone,"[255] but the long struggle "hurt his own reputation and the unity of his party".

'"[267] Asquith also appointed Sir William Robertson as Chief of the Imperial General Staff with increased powers, reporting directly to the Cabinet and with the sole right to give them military advice, relegating the Secretary of State for War to the tasks of recruiting and supplying the army.

[271] None of this saved the Dardanelles Campaign and the decision to evacuate was taken in December,[272] resulting in the resignation from the Duchy of Lancaster of Churchill,[273] who wrote, "I could not accept a position of general responsibility for war policy without any effective share in its guidance and control.

[280] This was an important sign of growing unity of action between the two men and it filled Margot Asquith with foreboding: "I look upon this as the greatest political blunder of Henry's lifetime ... We are out: it can only be a question of time now when we shall have to leave Downing Street.

"[317] Margot Asquith was also certain of Northcliffe's role, and of Lloyd George's involvement, although she obscured both of their names when writing in her diary: "I only hope the man responsible for giving information to Lord N- will be heavily punished: God may forgive him; I never can.

[373] Crawford records how little he and his senior Unionist colleagues were involved in the key discussions, and by implication, how much better informed were the press lords, writing in his diary: "We were all in such doubt as to what had actually occurred, and we sent out for an evening paper to see if there was any news!

[398] Lord Newton wrote in his diary of meeting Asquith at dinner a few days after the fall, "It became painfully evident that he was suffering from an incipient nervous breakdown and before leaving the poor man completely collapsed.

"[408] On 7 May 1918 a letter from a serving officer, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice, appeared in four London newspapers, accusing Lloyd George and Law of having misled the House of Commons in debates the previous month as to the manpower strength of the army in France.

[423] Even before the Armistice, Lloyd George had been considering the political landscape and, on 2 November 1918, wrote to Law proposing an immediate election with a formal endorsement—for which Asquith coined the name "Coupon", with overtones of wartime food rationing—for Coalition candidates.

[447] Travelling with Margot, his daughter Violet and a small staff, Asquith directed most of his campaign not against Labour, who were already in second place, but against the Coalition, calling for a less harsh line on German reparations and the Irish War of Independence.

[462] Until the Paisley by-election Asquith had accepted that the next government must be some kind of Liberal-Labour coalition, but Labour had distanced themselves because of his policies on the mines, the Russo-Polish War, education, the prewar secret treaties and the suppression of the Easter Rebellion.

[465] Lord Robert Cecil, a moderate and pro-League of Nations Conservative, had been having talks with Edward Grey about a possible coalition, and Asquith and leading Liberals Crewe, Runciman and Maclean had a meeting with them on 5 July 1921, and two subsequent ones.

His reputation was further damaged by his portrayal in Aldous Huxley's novel Crome Yellow and by the publication of the first volume of Margot's memoirs, which sold well in the UK and the United States, but were thought an undignified way for a former prime minister to make money.

[493] The Conservatives proposed a vote of censure against the Government for withdrawing their prosecution for sedition against the Daily Worker, and Asquith moved an amendment calling for a select committee (the same tactic he had employed over the Marconi scandal and the Maurice Debate).

"[567] The weight of opinion continues to agree with Asquith's own candid assessment, in a letter written in the midst of war in July 1916: "I am [as usual] encompassed by a cloud of worries, anxieties, problems and the rest.

[574] Hazlehurst, writing in 1970, felt there was still much to be gleaned from a critical review of Asquith's peacetime premiership, "certainly, the record of a prime minister under whom the nation goes to the brink of civil war [over Ireland] must be subjected to the severest scrutiny.