Assassination of Talaat Pasha

Tehlirian joined Operation Nemesis, a clandestine program carried out by the Dashnaktsutyun (the Armenian Revolutionary Federation); he was chosen for the mission to assassinate Talaat due to his previous success.

[3] Tehlirian claimed he had acted alone and that the killing was not premeditated, telling a dramatic and realistic, but untrue, story of surviving the genocide and witnessing the deaths of his family members.

[9] In 1918, Talaat told journalist Muhittin Birgen [tr], "I assume full responsibility for the severity applied" during the Armenian deportation and, "I absolutely don't regret my deed.

"[21] Arriving in Berlin on 10 November, Talaat stayed in a hotel in Alexanderplatz and a sanatorium in Neubabelsberg, Potsdam,[22] before moving into a nine-room apartment at Hardenbergstraße [de] 4, at today's Ernst-Reuter-Platz.

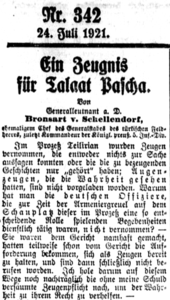

[26] The German government had intelligence that Talaat's name was first on an Armenian hit list and suggested he should stay at a secluded estate belonging to former Ottoman chief of staff Fritz Bronsart von Schellendorf in Mecklenburg.

Using a false passport under the name Ali Saly Bey, he traveled freely throughout continental Europe despite being wanted by the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire for his crimes.

[32] Talaat and other CUP exiles were convicted and sentenced to death in absentia for the "massacre and annihilation of the Armenian population of the Empire" by the Ottoman Special Military Tribunal on 5 July 1919.

[33] After it became clear that no one else would bring the perpetrators of the genocide to justice,[35] the Dashnaktsutyun, an Armenian political party, set up the secret Operation Nemesis, headed by Armen Garo, Shahan Natalie, and Aaron Sachaklian.

[44] After the war, Tehlirian went to Constantinople, where he assassinated Harutiun Mgrditichian, who had worked for the Ottoman secret police and helped compile the list of Armenian intellectuals who were deported on 24 April 1915.

[45] In mid-1920, the Nemesis organization paid for Tehlirian to travel to the United States, where Garo briefed him that the death sentences pronounced against the major perpetrators had not been carried out, and that the killers continued their anti-Armenian activities from exile.

Jäckh attempted to convince the police to surrender the body using his authority as a Foreign Office official, but they refused to do so before the homicide squad arrived.

[59] Initially, Talaat's friends hoped he could be buried in Anatolia, but neither the Ottoman government in Constantinople nor the Turkish nationalist movement in Ankara wanted the body; it would be a political liability to associate themselves with the man considered the worst criminal of World War I.

[65] In late April, national-liberal politician Gustav Stresemann of the German People's Party proposed a public commemoration to honor Talaat.

[86] Their strategy was successful, as the social-democratic newspaper Vorwärts noted: "In reality it was the blood-stained shadow of Talât Pasha who was sitting on the defendant's bench; and the true charge was the ghastly Armenian Horrors, not his execution by one of the few victims left alive.

[76] Along with the enormity of Talaat's crimes, the defense argument rested on Tehlirian's traumatized mental state, which could make him not liable for his actions according to the German law of temporary insanity, section 51 of the penal code.

[89] The prosecution applied for the case to be heard in camera to minimize exposure, but the Foreign Office rejected this solution, fearing that secrecy would not improve Germany's reputation.

[90] Historian Carolyn Dean writes that the attempt to complete the trial quickly and positively portray Germany's actions during the war "inadvertently transformed Tehlirian into a symbol of human conscience tragically compelled to gun down a murderer for want of justice.

[107] Historian Tessa Hofmann says that, while false, Tehlirian's testimony featured "extremely typical and essential elements of the collective fate of his compatriots".

[117] Mentioning the collection of Foreign Office documents he edited, Germany and Armenia, Lepsius stated that hundreds more similar testimonies existed like those heard by the court; he estimated one million Armenians were killed overall.

[133] Five expert witnesses testified about Tehlirian's mental state and whether it absolved him from criminal responsibility for his actions according to German law;[78] all agreed that he suffered from regular bouts of "epilepsy" due to what he experienced in 1915.

[137] Neurologist and professor Richard Cassirer testified that "emotional turbulence was the root cause of his condition", and that "affect epilepsy" completely changed his personality.

At 9:15 a.m. on the second day, the judge addressed the jury, stating they needed to answer the following questions: "[First, is] the defendant, Soghomon Tehlirian, guilty of having killed, with premeditation, another human being, Talât Pasha, on 15 March 1921, in Charlottenburg?...

[146] Furthermore, the defense noted that "deliberation" (Überlegung) in German case law refers to the time at which the decision to kill is made, excluding other preparations.

A typical example of coverage was in Vossische Zeitung, which acknowledged Talaat's role in attempting to "exterminat[e] all reachable members of the [Armenian] tribe", but advanced several justifications for the genocide.

[171] The Deutsche Allgemeine Zeitung launched an anti-Armenian campaign claiming that backstabbing and murder such as Tehlirian had carried out was "the true Armenian manner".

[185] Following Talaat's assassination, Ankara newspapers praised him as a great revolutionary and reformer; Turkish nationalists told the German consul that he remained "their hope and idol".

[189] In his newspaper, published in Constantinople, Armenian socialist Dikran Zaven [hy] expressed hope that "Turks aware of the true interests of their country will not count this former minister among their good statesmen".

[192] Historian Hans-Lukas Kieser states that the "assassination perpetuated the sick relationship of a victim in quest of revenge with a perpetrator entrenched in defiant denial".

[198] In 1943, at the request of the Turkish government, Talaat was exhumed and received a state funeral at the Monument of Liberty, Istanbul, originally dedicated to those who lost their lives preventing the 1909 Ottoman countercoup.

[207] Those who defended Sholem Schwarzbard's assassination of Ukrainian anti-Jewish pogromist Symon Petliura in 1926 cited Tehlirian's trial; a French court subsequently acquitted him.