Worship of heavenly bodies

Mesopotamia is worldwide the place of the earliest known astronomer and poet by name: Enheduanna, Akkadian high priestess to the lunar deity Nanna/Sin and princess, daughter of Sargon the Great (c. 2334 – c. 2279 BCE).

Archibald Sayce (1913) argues for a parallelism of the "stellar theology" of Babylon and Egypt, both countries absorbing popular star-worship into the official pantheon of their respective state religions by identification of gods with stars or planets.

[4] Astral religion does not appear to have been common in the Levant prior to the Iron Age, but becomes popular under Assyrian influence around the 7th-century BCE.

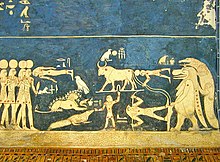

[7] Evidence suggests that the observation and veneration of celestial bodies played a significant role in Egyptian religious practices, even before the development of a dominant solar theology.

The early Egyptians associated celestial phenomena with divine forces, seeing the stars and planets as embodiments of gods who influenced both the heavens and the earth.

[8] Direct evidence for astral cults, seen alongside the dominant solar theology which arose before the Fifth Dynasty, is found in the Pyramid Texts.

[9] These texts, among the oldest religious writings in the world, contain hymns and spells that not only emphasize the importance of the Sun God Ra but also refer to stars and constellations as powerful deities that guide and protect the deceased Pharaoh in the afterlife.

This connection between Sopdet and the Nile flood underscores the profound link between celestial phenomena and earthly prosperity in ancient Egyptian culture.

[18] Additionally, the alignment of architectural structures, such as pyramids and temples, with astronomical events reveals the deliberate integration of cosmological concepts into Egypt's built environment.

[25] However, apart from the fact that it contains traces of Babylonian and Hellenistic religion, and that an important place was taken by planets (to whom ritual sacrifices were made), little is known about Harranian Sabianism.

[29] This group still held on to a pagan belief related to Babylonian religion, in which Mesopotamian gods had already been venerated in the form of planets and stars since antiquity.

[30] According to Ibn al-Nadim, our only source for these star-worshipping 'Sabians of the Marshes', they "follow the doctrines of the ancient Aramaeans [ʿalā maḏāhib an-Nabaṭ al-qadīm] and venerate the stars".

[31] However, there is also a large corpus of texts by Ibn Wahshiyya (died c. 930), most famously his Nabataean Agriculture, which describes at length the customs and beliefs — many of them going back to Mespotamian models — of Iraqi Sabians living in the Sawād.

This evolution marked a shift from the earlier concept of Shangdi to a more abstract and universal principle that guided both natural and human affairs.

[36][37] This mandate was reinforced through celestial observations and rituals, as astrological phenomena were interpreted as omens reflecting the favor or disfavor of Heaven.

The Big Dipper was associated with cosmic order and governance, while the North Star was considered the throne of the celestial emperor.

These stars played a crucial role in state rituals, where the Emperor’s ability to align these celestial forces with earthly governance was seen as essential to his legitimacy.

[43] Worship of Heaven in the southern suburb of the capital was initiated in 31 BCE and firmly established in the first century CE (Western Han).

[45] During the Tang dynasty, Chinese Buddhism adopted Taoist Big Dipper worship, borrowing various texts and rituals which were then modified to conform with Buddhist practices and doctrines.

During the reign of Emperor Tenji (661–672), the toraijin were resettled in the easternmost parts of the country; as a result, Myōken worship spread throughout the eastern provinces.

[51] By the Heian period, pole star worship had become widespread enough that imperial decrees banned it for the reason that it involved "mingling of men and women", and thus caused ritual impurity.

Pole star worship was also forbidden among the inhabitants of the capital and nearby areas when the imperial princess (Saiō) made her way to Ise to begin her service at the shrines.

[64] The Inca civilization engaged in star worship,[65] and associated constellations with deities and forces, while the Milky Way represented a bridge between earthly and divine realms.

[69] While the planetary worship was linked to devils (shayāṭīn),[70] abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi reported that the planets are considered angelic spirits at the service of God.

[71] He refutes the notion that astrology is based on the interference of demons or "guesswork" and established the study of the planets as a form of natural sciences.

As the spiritual powers allegedly emanating from the planets are explained to derive from the Anima mundi, the writings clearly distanced them from demonic entities such as jinn and devils.

Originally an 11th-century Buddhist temple dedicated to Myōken, converted into a Shinto shrine during the Meiji period .