P-factor

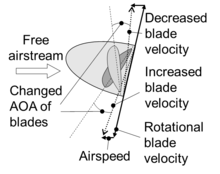

However, at lower speeds, the aircraft will typically be in a nose-high attitude, with the propeller disc rotated slightly toward the horizontal.

[1][5] If using a clockwise turning propeller (as viewed by the pilot) the aircraft has a tendency to yaw to the left when climbing and right when descending.

The yaw is noticeable when adding power, though it has additional causes including the spiral slipstream effect.

In a fixed-wing aircraft, there is usually no way to adjust the angle of attack of the individual blades of the propellers, therefore the pilot must contend with P-factor and use the rudder to counteract the shift of thrust.

The fact that the left-right pull tendency reverses when descending, shows that differences in angle of attack on the left and right sides of the prop overwhelm other effects like the spiral slipstream.

The effect is not so apparent during the landing, flare and rollout, given the relatively low power setting (propeller RPM).

However, should the throttle be suddenly advanced with the tail-wheel in contact with the runway, then anticipation of this nose-left tendency is prudent.

With engines rotating in the same direction, P-factor will affect the minimum control speeds (VMC) of the aircraft in asymmetric powered flight.

[8] The never-exceed speed (VNE) of a helicopter will be chosen in part to ensure that the backwards-moving blade does not stall.