Athenian democracy

This approximately translates as the "people's hand of power", and in the context of the play it acts as a representation of the popular requirement that the king needed to get approval from the Demos in a public assembly before taking any large decision (in this case of allowing the suppliant daughters of Danaos to take refuge in the city-state of Argos), i.e. that authority as implemented by the people in the Assembly has veto power over a king.

[13][14] While the laws, later come to be known as the Draconian Constitution, were largely harsh and restrictive, with nearly all of them later being repealed, the written legal code was one of the first of its kind and considered to be one of the earliest developments of Athenian democracy.

[15] In 594 BC, Solon was appointed premier archon and began issuing economic and constitutional reforms in an attempt to alleviate some of the conflict that was beginning to arise from the inequities that permeated throughout Athenian society.

His reforms ultimately redefined citizenship in a way that gave each free resident of Attica a political function: Athenian citizens had the right to participate in assembly meetings.

While Ephialtes's opponents were away attempting to assist the Spartans, he persuaded the Assembly to reduce the powers of the Areopagus to a criminal court for cases of homicide and sacrilege.

[21] In the wake of Athens's disastrous defeat in the Sicilian campaign in 413 BC, a group of citizens took steps to limit the radical democracy they thought was leading the city to ruin.

[22] After a year, pro-democracy elements regained control, and democratic forms persisted until the Macedonian army of Phillip II conquered Athens in 338 BC.

Modern democracies have also created systems to include a wider variety of viewpoints, which lowers the dangers of a small number of people holding all the power and promotes an informed voter.

However, the governors, like Demetrius of Phalerum, appointed by Cassander, kept some of the traditional institutions in formal existence, although the Athenian public would consider them to be nothing more than Macedonian puppet dictators.

The victorious Roman general, Publius Cornelius Sulla, left the Athenians their lives and did not sell them into slavery; he also restored the previous government, in 86 BC.

[28] After Rome became an Empire under Augustus, the nominal independence of Athens dissolved and its government converged to the normal type for a Roman municipality, with a Senate of decuriones.

[34] Also excluded from voting were citizens whose rights were under suspension (typically for failure to pay a debt to the city: see atimia); for some Athenians, this amounted to permanent (and in fact inheritable) disqualification.

Given the exclusive and ancestral concept of citizenship held by Greek city-states, a relatively large portion of the population took part in the government of Athens and of other radical democracies like it, compared to oligarchies and aristocracies.

[30] Some Athenian citizens were far more active than others, but the vast numbers required for the system to work testify to a breadth of direct participation among those eligible that greatly surpassed any present-day democracy.

[39] In addition to being barred from any form of formal participation in government, women were also largely left out of public discussions and speeches with orators going as far as leaving out the names of wives and daughters of citizens or finding round about ways of referring to them.

With this in mind, they feared that women may engage in affairs and have sons out of wedlock which would jeopardize the Athenian system of property and inheritance between heirs as well as the citizenry of potential children if their parentage was called into question.

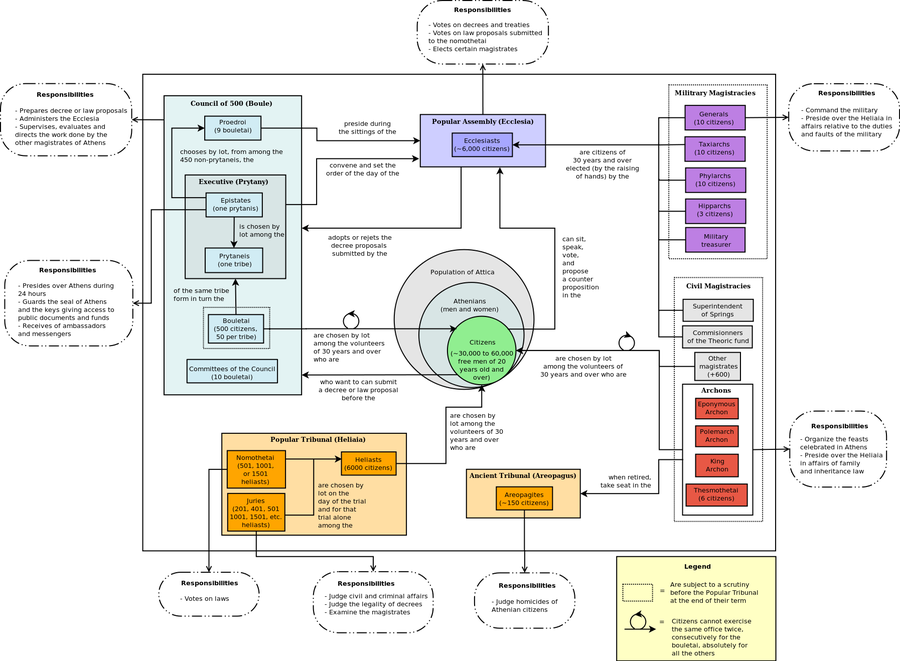

The assembly had four main functions: it made executive pronouncements (decrees, such as deciding to go to war or granting citizenship to a foreigner), elected some officials, legislated, and tried political crimes.

Ostracism, a unique feature of Athenian democracy introduced in the early 5th century BCE, allowed the Assembly to exile citizens deemed threats to the state's stability.

As noted by Starr, ostracism exemplified Athens' efforts to safeguard democracy by placing constraints on influential figures without resorting to more severe punitive actions, thereby balancing political stability with democratic freedom.

In the 5th century, public slaves forming a cordon with a red-stained rope herded citizens from the agora into the assembly meeting place (Pnyx), with a fine being imposed on those who got the red on their clothes.

The Boule's roles in public affairs included finance, maintaining the military's cavalry and fleet of ships, advising the generals, approving of newly elected magistrates, and receiving ambassadors.

Unlike officeholders, the citizen initiator was not voted on before taking up office or automatically reviewed after stepping down; these institutions had, after all, no set tenure and might be an action lasting only a moment.

[64][65] Although, voters under Athenian democracy were allowed the same opportunity to voice their opinion and to sway the discussion, they were not always successful, and, often, the minority was forced to vote in favor of a motion that they did not agree with.

While there seems to have also been a type of citizen assembly (presumably of the hoplite class), the archons and the body of the Areopagus ran the state and the mass of people had no say in government at all before these reforms.

In each of the ten "main meetings" (kuriai ekklesiai) a year, the question was explicitly raised in the assembly agenda: were the office holders carrying out their duties correctly?

[85]Thucydides, from his aristocratic and historical viewpoint, reasoned that a serious flaw in democratic government was that the common people were often much too credulous about even contemporary facts to rule justly, in contrast to his own critical-historical approach to history.

His The Republic, The Statesman, and Laws contained many arguments against democratic rule and in favour of a much narrower form of government: "The organization of the city must be confided to those who possess knowledge, who alone can enable their fellow-citizens to attain virtue, and therefore excellence, by means of education.

At times the imperialist democracy acted with extreme brutality, as in the decision to execute the entire male population of Melos and sell off its women and children simply for refusing to become subjects of Athens.

Several German philosophers and poets took delight in what they saw as the fullness of life in ancient Athens, and not long afterwards "English liberals put forward a new argument in favor of the Athenians".

In opposition, thinkers such as Samuel Johnson were worried about the ignorance of democratic decision-making bodies, but "Macaulay and John Stuart Mill and George Grote saw the great strength of the Athenian democracy in the high level of cultivation that citizens enjoyed, and called for improvements in the educational system of Britain that would make possible a shared civic consciousness parallel to that achieved by the ancient Athenians".