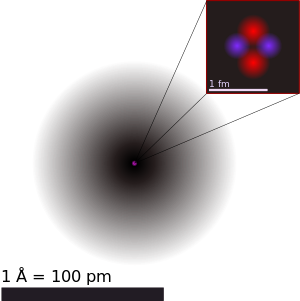

Atomic nucleus

The nucleus was discovered in 1911, as a result of Ernest Rutherford's efforts to test Thomson's "plum pudding model" of the atom.

Knowing that atoms are electrically neutral, J. J. Thomson postulated that there must be a positive charge as well.

In his plum pudding model, Thomson suggested that an atom consisted of negative electrons randomly scattered within a sphere of positive charge.

He reasoned that if J. J. Thomson's model were correct, the positively charged alpha particles would easily pass through the foil with very little deviation in their paths, as the foil should act as electrically neutral if the negative and positive charges are so intimately mixed as to make it appear neutral.

This justified the idea of a nuclear atom with a dense center of positive charge and mass.

The nucleus of an atom consists of neutrons and protons, which in turn are the manifestation of more elementary particles, called quarks, that are held in association by the nuclear strong force in certain stable combinations of hadrons, called baryons.

The nuclear strong force has a very short range, and essentially drops to zero just beyond the edge of the nucleus.

However, this type of nucleus is extremely unstable and not found on Earth except in high-energy physics experiments.

The proton has an approximately exponentially decaying positive charge distribution with a mean square radius of about 0.8 fm.

However, the residual strong force has a limited range because it decays quickly with distance (see Yukawa potential); thus only nuclei smaller than a certain size can be completely stable.

The effective absolute limit of the range of the nuclear force (also known as residual strong force) is represented by halo nuclei such as lithium-11 or boron-14, in which dineutrons, or other collections of neutrons, orbit at distances of about 10 fm (roughly similar to the 8 fm radius of the nucleus of uranium-238).

Halo nuclei form at the extreme edges of the chart of the nuclides—the neutron drip line and proton drip line—and are all unstable with short half-lives, measured in milliseconds; for example, lithium-11 has a half-life of 8.8 ms. Halos in effect represent an excited state with nucleons in an outer quantum shell which has unfilled energy levels "below" it (both in terms of radius and energy).

This is due to two reasons: Historically, experiments have been compared to relatively crude models that are necessarily imperfect.

For stable nuclei (not halo nuclei or other unstable distorted nuclei) the nuclear radius is roughly proportional to the cube root of the mass number (A) of the nucleus, and particularly in nuclei containing many nucleons, as they arrange in more spherical configurations: The stable nucleus has approximately a constant density and therefore the nuclear radius R can be approximated by the following formula, where A = Atomic mass number (the number of protons Z, plus the number of neutrons N) and r0 = 1.25 fm = 1.25 × 10−15 m. In this equation, the "constant" r0 varies by 0.2 fm, depending on the nucleus in question, but this is less than 20% change from a constant.

This formula is successful at explaining many important phenomena of nuclei, such as their changing amounts of binding energy as their size and composition changes (see semi-empirical mass formula), but it does not explain the special stability which occurs when nuclei have special "magic numbers" of protons or neutrons.

The electric repulsion between each pair of protons in a nucleus contributes toward decreasing its binding energy.

In the above models, the nucleons may occupy orbitals in pairs, due to being fermions, which allows explanation of even/odd Z and N effects well known from experiments.

The exact nature and capacity of nuclear shells differs from those of electrons in atomic orbitals, primarily because the potential well in which the nucleons move (especially in larger nuclei) is quite different from the central electromagnetic potential well which binds electrons in atoms.

While each nucleon is a fermion, the {NP} deuteron is a boson and thus does not follow Pauli Exclusion for close packing within shells.

An example is the stability of the closed shell of 50 protons, which allows tin to have 10 stable isotopes, more than any other element.

This has led to complex post hoc distortions of the shape of the potential well to fit experimental data, but the question remains whether these mathematical manipulations actually correspond to the spatial deformations in real nuclei.

Problems with the shell model have led some to propose realistic two-body and three-body nuclear force effects involving nucleon clusters and then build the nucleus on this basis.