Satisfaction theory of atonement

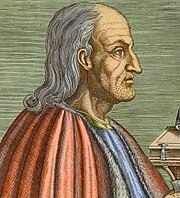

The theory draws primarily from the works of Anselm of Canterbury, specifically his Cur Deus Homo ('Why Was God a Man?').

Anselm's theory was a precursor to the theology of later theologians like John Calvin, who taught the idea of Christ suffering the Father's just punishment as a vicarious substitute.

Both affirm the substitutionary and vicarious nature of the atonement, but penal substitution offers a specific explanation as to what the suffering is for: punishment.

The early Church Fathers, including Athanasius and Augustine, taught that through Christ's suffering in humanity's place, he overcame and liberated us from death and the devil.

[citation needed] Anselm of Canterbury first articulated the satisfaction view in his Cur Deus Homo?, as a modification to the ransom theory that was postulated at the time in the West.

"[5] This debt creates an imbalance in the moral universe; God cannot simply ignore it according to Anselm.

[7] In light of this view, the "ransom" that Jesus mentions in the Gospels would be a sacrifice and a debt paid only to God the Father.

Anselm did not speak directly to the later Calvinist concern for the scope of the satisfaction for sins, whether it was paid for all mankind universally or only for limited individuals, but indirectly his language suggests the former.

[8] Thomas Aquinas later specifically attributes a universal scope to this atonement theory in keeping with previous Catholic dogma, as do Lutherans at the time of the Reformation.

[13] For Aquinas, the Passion of Jesus provided the merit needed to pay for sin: "Consequently Christ by His Passion merited salvation, not only for Himself, but likewise for all His members,"[14] and that the atonement consisted in Christ's giving to God more "than was required to compensate for the offense of the whole human race."

This sounds like penal substitution, but Aquinas is careful to say that he does not mean this to be taken in legal terms:[16] "If we speak of that satisfactory punishment, which one takes upon oneself voluntarily, one may bear another's punishment….

As such, he wanted to solve the problem of Christ's atonement in a way that he saw as just to the Scriptures and Church Fathers, rejecting the need for condign merit.

That is, when Jesus died on the cross, his death paid the penalty at that time for the sins of all those who are saved (past, present, and future).

[22] One obviously necessary feature of this idea is that Christ's atonement is limited in its effect only to those whom God has chosen to be saved, since the debt for sins was paid at a particular point in time (at the crucifixion).

John Stott has stressed that this must be understood not as the Son placating the Father, but rather in Trinitarian terms of the Godhead initiating and carrying out the atonement, motivated by a desire to save humanity.