Augustine Chacon

According to Old West historian Marshall Trimble, Chacon was "one of the last of the hard-riding desperados who rode the hoot-owl trail in Arizona around the turn of the century."

He is first recorded in history as being a peace officer in the town of Sierra del Tigre, though he also found work hauling wood and ore at some point.

Ben Ollney's brother lived at Whitlock Springs and quickly organized a posse of six men to go after Chacon, who by that time was fleeing south towards the border.

[2][3] According to author R. Michael Wilson, the entire Ollney family[clarification needed] was killed in Whitlock Springs two days later, but Chacon claimed he was at a Mexican woodcutter's camp when the murders occurred, tending to his wound and accompanied by a pair of Arizona train robbers, Burt Alvord and Billy Stiles.

He was arrested near Fort Apache while visiting a girl and the next day a lynch mob formed to carry out an illegal hanging.

Later that night, Slaughter and his then-deputy Burt Alvord surrounded the canvas tent Chacon was sleeping in, but when they called on him to surrender, the bandit jumped up and started running out the back entrance.

But when the lawmen got down to the bottom, they found no body and decided Chacon must have tripped on a rope at the foot of the tent and the shotgun blast passed over his head.

On the night of December 18, Chacon and two of his followers, Pilar Franco and Leonardo Morales, entered McCormack's store, which was managed by a man named Paul Becker.

After stabbing the manager in his sleeping quarters, the bandits looted the place and then headed for their cabin, which was located on top of a steep hill that overlooked the town.

As Davis and his deputies approached the cabin, suddenly Chacon and his men burst out the front door, running for a pile of boulders and firing their guns wildly.

A few of the possemen went after the fleeing bandits, killing them both, and when the return fire ceased they were able to move in and capture Chacon, who was temporarily paralyzed by bullet wounds to his chest and shoulder.

Armed robbery and rustling was so widespread that in March 1901 the territorial governor, Oakes Murphy, authorized the re-establishment of the Arizona Rangers.

Burton C. Mossman was the first captain of the unit and his final accomplishment before resigning was tricking Augustine Chacon into crossing the border, where he could be apprehended legally.

To do this, Mossman came up with an idea that involved posing as an outlaw and recruiting the train robber Burt Alvord, who was a friend of Chacon, to use him as a stool pigeon.

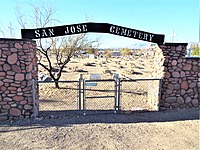

On April 22, 1902, after traveling for several days by wagon and on horseback, Mossman discovered Alvord's hideout, a small hut located some distance away from San Jose de Pima.

The captain approached the hut unarmed and by chance found Alvord standing alone outside while the rest of the gang played cards inside.

Another outlaw Billy Stiles acting as their messenger, for it would take a while for Alvord to find Chacon and convince him to cross the Arizona border and somebody had to warn the captain when the bandits arrived.

When he finally did catch up with Chacon, over three months later, Alvord first accompanied him to the Yaqui River to sell stolen horses before going all the way back to the border.

As the bandits were nearing the rendezvous, Alvord sent Stiles ahead to tell Mossman to meet them just south of the border, at the Socorro Mountain Springs in Sonora.

There, after exchanging names, Mossman and the others agreed to cross the border back into Arizona the next day so they could steal some horses from Greene's Ranch that night.

The bandit chief, who had for over a decade eluded the law, asked for a cigarette and a cup of coffee before death and then began an unprepared thirty-minute speech to the crowd.

Speaking in Spanish with an English interpreter, Chacon claimed he was innocent of killing his friend, Pablo Salcido, or anybody else for that matter, but he did say that he was guilty of stealing and "many other things."

On the day after the execution, the Arizona Bulletin reported: "[A] nervier man than Augustine Chacon never walked to the gallows, and his hanging was a melodramatic spectacle that will never be forgotten by those who witnessed it.