Augustinian theodicy

As such, it attempts to explain the probability of an omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving) God amid evidence of evil in the world.

A number of variations of this kind of theodicy have been proposed throughout history; their similarities were first described by the 20th-century philosopher John Hick, who classified them as "Augustinian".

They typically assert that God is perfectly (ideally) good, that he created the world out of nothing, and that evil is the result of humanity's original sin.

The entry of evil into the world is generally explained as consequence of original sin and its continued presence due to humans' misuse of free will and concupiscence.

Augustine believed in the existence of a physical Hell as a punishment for sin, but argued that those who choose to accept the salvation of Jesus Christ will go to Heaven.

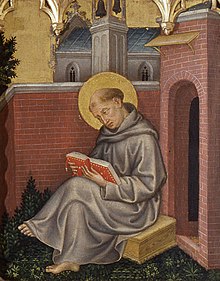

In the 13th century, Thomas Aquinas – influenced by Augustine – proposed a similar theodicy based on the view that God is goodness and that there can be no evil in him.

Plantinga's adapted Augustinian theodicy, the free will defence – which he proposed in the 1980s – attempts to answer only the logical problem of evil.

[3] Theodicy is an attempt to reconcile the existence and nature of God with evidence of evil in the world by providing valid explanations for its occurrence.

All versions of this theodicy accept the theological implications of the Genesis creation narrative, including the belief that God created human beings without sin or suffering.

Evil is believed to be a just punishment for the fall of man: when Adam and Eve first disobeyed God and were exiled from the Garden of Eden.

This helped him develop a response to the problem of evil from a theological (and non-Manichean) perspective,[10] based on his interpretation of the first few chapters of Genesis and the writings of Paul the Apostle.

[11] In City of God, Augustine developed his theodicy as part of his attempt to trace human history and describe its conclusion.

[20] Thomas Aquinas, a thirteenth-century scholastic philosopher and theologian heavily influenced by Augustine,[21] proposed a form of the Augustinian theodicy in his Summa Theologica.

[32] The philosopher Peter van Inwagen put forward an original formulation of the Augustinian theodicy in his book The Problem of Evil.

[citation needed] In response, van Inwagen argues that there is no non-arbitrary amount of evil necessary for God to fulfil his plan, and he does this by employing a formulation of the Sorites paradox.

[35] Augustine replied by arguing that the sin of Adam constrained human freedom, in a way similar to the formation of habits.

[39] Ingram and Streng argued that the Augustinian theodicy fails to account for the existence of evil before Adam's sin, which Genesis presents in the form of the serpent's temptation.

For Zaccaria, Augustine's perception of evil as a privation did not satisfactorily answer the questions of modern society as to why suffering exists.

Hick supported the views of the German theologian Friedrich Schleiermacher, which he classified as Irenaean, who argued that the world is perfectly suited for the moral development of humans and that this justifies the existence of evil.

[43] In God, Power and Evil: A Process Theodicy, published in 1976, David Ray Griffin criticised Augustine's reliance on free will and argued that it is incompatible with divine omniscience and omnipotence.

[46] In the 1970s, Alvin Plantinga presented a version of the free will defence which, he argued, demonstrated that the existence of an omnipotent benevolent God and of evil are not inconsistent.

[53] The theologian Alister McGrath has noted that, because Plantinga only argued that the coexistence of God and evil are logically possible, he did not present a theodicy, but a defence.

[56] The twentieth-century philosopher Reinhold Niebuhr attempted to reinterpret the Augustinian theodicy in the light of evolutionary science by presenting its underlying argument without mythology.

Niebuhr proposed that Augustine rejected the Manichean view that grants evil ontological existence and ties humans' sin to their created state.

He argued that the logic behind Augustine's theodicy described sin as inevitable but unnecessary, which he believed captured the argument without relying on a literal interpretation of the fall, thus avoiding critique from scientific positions.