Australian Senate

Senators are popularly elected under the single transferable vote system of proportional representation in state-wide and territory-wide districts.

According to convention, the Senate plays no role in the formation of the executive government and the prime minister is drawn from the majority party or coalition in the House.

Since the late 20th century, it has been rare for governments to hold a majority in the Senate and the balance of power has typically rested with minor parties and independents.

The power to bring down the government and force elections by blocking supply also exists, as happened for the first and thus far only time during the 1975 constitutional crisis.

In contrast to countries employing a pure Westminster system the Senate plays an active role in legislation and is not merely a chamber of review.

[1][2] This was done to give less populous states a real influence in the Parliament, while also maintaining the traditional review functions upper houses have in the Westminster system.

That degree of equality between the Senate and House of Representatives reflects the desire of the Constitution's authors to prevent the more populous states totally dominating the legislative process.

In practice, however, most legislation (except for private member's bills) in the Australian Parliament is initiated by the government, which has control over the lower house.

The results have no direct legislative power, but are valuable forums that raise many points of view that would otherwise not receive government or public notice.

At this time the number of senators was expanded from 36 to 60 and it was argued that a move to proportional representation was needed to even up the balance between both major parties in the chamber.

The change in voting systems has been described as an "institutional revolution" that has had the effect of limiting the government's ability to control the chamber, as well as helping the rise of Australian minor parties.

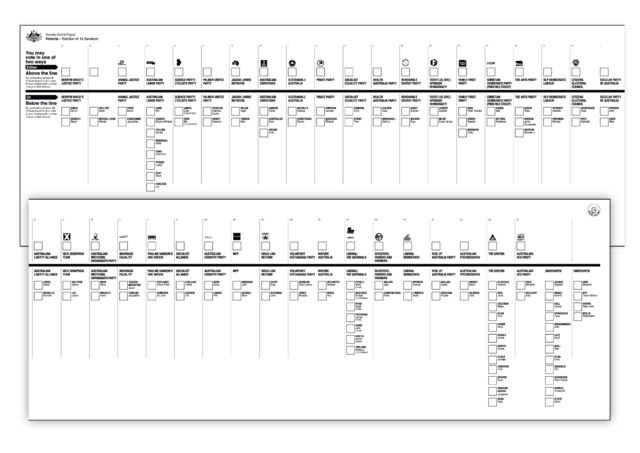

For above the line, voters are instructed to number at least their first six preferences; however, a "savings provision" is in place to ensure that ballots will still be counted if less than six are given.

[13] The changes were subject to a challenge in front of High Court of Australia by sitting South Australian Senator Bob Day of the Family First Party.

The term of the four senators from the territories is not fixed, but is defined by the dates of the general elections for the House of Representatives, the period between which can vary greatly, to a maximum of three years and three months.

Whether a government facing a Senate that blocks supply is obliged to either resign or call an election was one of the major disputes of the 1975 constitutional crisis.

A two-party system became ensconced in both houses of parliament following the "fusion" of the non-Labor parties in 1909, largely as a response to the discipline of the ALP.

[37] Votes on party lines soon became a regular feature of debate, with corresponding criticisms that the Senate had merely become a rubber stamp for the government rather than filling the role of a states' house.

[41] These outcomes, while still uncommon, led the Senate to be perceived as a weak institution serving as a rubber stamp and contributed to calls for reform.

Consideration of some bills is completed in a single day, while complex or controversial legislation may take months to pass through all stages of Senate scrutiny.

One of the most significant powers is the ability to summon people to attend hearings in order to give evidence and submit documents.

[57] Other powers include the ability to meet throughout Australia, to establish subcommittees and to take evidence in both public and private hearings.

Every participant, including committee members and witnesses giving evidence, is protected from being prosecuted under any civil or criminal action for anything they may say during a hearing.

Nevertheless, the existence of minor parties holding the balance of power in the Senate has made divisions in that chamber more uncertain than in the House of Representatives.

At the end of that period the doors are locked and a vote is taken, by identifying and counting senators according to the side of the chamber on which they sit (ayes to the right of the chair, noes to the left).

[68] The controversy that surrounded these examples demonstrated both the importance of backbenchers in party policy deliberations and the limitations to their power to influence outcomes in the Senate chamber.

In September 2008, Barnaby Joyce became leader of the Nationals in the Senate, and stated that his party in the upper house would no longer necessarily vote with their Liberal counterparts.

On 8 October 2003, the then Prime Minister John Howard initiated public discussion of whether the mechanism for the resolution of deadlocks between the Houses should be reformed.

The Senate has the same legislative power as the House of Representatives, except it may not originate or amend taxing or appropriation bills; they may only pass or reject them.

The ability to block the annual appropriations bills required to fund the government ("supply") was exercised in the 1975 Australian constitutional crisis.

The deadlock ended in November 1975 when Governor-General Sir John Kerr dismissed Whitlam's government and appointed Opposition Leader Fraser as Prime Minister, on the condition that elections for both Houses of parliament be held.